When we look at ancient monuments today, it’s often very challenging to visualise the society and community that once built and dwelt there. Indeed, for any wandering the streets of Antrim today, I doubt any would guess at what was once a thriving Christian monastic community. And not just any monastic community, but one which endured for over 1,000 years. Only a lone stone tower remains dating as far back as the 7th century. Like many of its counterparts, the tower served both practical and symbolic functions: a refuge in times of danger, a landmark for travellers, and a visible sign of ecclesiastical authority. But also a pointer to a historic town now lost to time and history.

So while the monastery that once surrounded it has long vanished, the tower remains remarkably intact, offering a direct link to the world of early Irish Christianity. In this post we will consider the history, archaeology, and legacy, of Antrim’s Round Tower. We will consider the evidence for what was once one of the most significant Christian communities in Ulster and its subsequent decline. Through it we will glimpse into Antrim’s ancient history as a centre of Christian learning and worship, and the wider political sites which grew up around it.

Antrim’s Monastic Community

Antrim was once the site of a thriving monastic community as far back as the 5th century. It’s believed that the original monastery was founded St. Aedh in 495AD, though some suggest it may have been St. Comgall of Bangor. Whatever the case, it’s worth pausing to set the date in context. For St. Patrick’s himself had only arrived in Ireland in the early 5th century, making this as one of the earliest Christian communities in Ulster (likely one or two generations after Ireland’s patron saint).

Archaeological excavations of the site and neighbouring area found evidence of prehistoric activity including a ring barrow, pits, and what is thought to have been a house. This follows a common archaeological pattern where sites are typically reoccupied over phases of history. It makes sense given the site’s strategic position near Lough Neigh, with access to rich fishing grounds and fertile lands. Waterways were the highways of ancient Ireland, and Lough Neagh connected Antrim to major routes across Ulster and beyond.

Archaeological Evidence

But it gets more interesting as we move on to the early Medieval period, where finds include:

“A field system associated with a house was also found, and an Early Medieval occupation site yielded an enclosure, souterrains and houses bordering a cobbled roadway. An Early Medieval stone built house, more field systems and a single isolated feature containing a beaker pot were also found.”

A cobbled road suggests an important route – for you only go to the effort of building a road when you want to connect places of some importance. Moreover, the stone house and tower indicates wealth as most buildings during this period were still made of wood. The souterrain would have been built possibly as both a safe haven or somewhere to store valuable goods. Together these finds begin to develop a picture of a flourishing wealthy community. Surrounding the monastery lay the wider settlement of laypeople, craftsmen, and dependants who provided goods and labour. In this way, the site was a focal point within a much larger social and religious community.

Therefore, while many monastic communities were able to function in relative isolation, Antrim’s appears to have been more connected both politically and religiously.

Religious Importance

Antrim’s round tower is generally dated to the 10th century, aligning it with a period of consolidation for the church in Ulster. Indeed, the information sign at the site states it was built in the 10th or 11th century. Sites like the Rock of Cashel are good examples of this phase of Christian architecture. However, there’s a theory that Antrim’s Round Tower was actually “built by Goban Saer, in the seventh century, a celebrated architect of that age.”1 If true, it would make this one of the earliest round towers with deep symbolic significance both as a form of architectural art, economic prestige, and functional defense. To afford to build such a challenging building would have required significant income and skill reinforcing the view that this was a key site for early Christianity in Ireland.

This view is reinforced by the religious connections between the site and others in the region. For instance, one account claims that the revered remains of St. Comgall where moved to Antrim from the monastic settlement at Bangor following a Viking raid. To have chosen Antrim over and above other closer sites (e.g. Nendrum) suggests the site was considered at least suitably important. What we can say with more certainty is that Antrim was part of a dense network of monastic sites in Ulster. Together, these monasteries formed centres of faith, learning, and artistic production, while also shaping the political landscape through their alliances with ruling dynasties.

What I find even more compelling, however, is when we consider the wider community that appears to have grown up around the site.

Fort of Rathmore

Barely 2 miles away sat the neighbouring Fort of Rathmore – the royal seat of the Dál nAraide during the early medieval period (8-11th centuries). Given their close proximity and the monastic site’s earlier provenance, suggests that the political followed the religious. The kingdom of Dál nAraide was one of the most powerful at this time, stretching from the Hebrides in the north deep into Ulster. It controlled key strongholds like Dunseverick along the north and eastern coastlines.

While history doesn’t appear to tell us why they chose this location, it would have been relatively central within the kingdom whilst also well protected from opportunistic raiders. But I’d suggest the presence of a thriving religious community and all the economy that would have surrounded it, likely also played a key part.

Destruction and decline

The site appears to have flourished until at least the 11th century when it suffered the fate of many monastic sites of that time – pillaged by Viking raiders. The Annals claim it was plundered in 1018 and it was later burned in 1147. But this suggests that the site was rebuilt and continued, albeit likely on a smaller scale. Indeed, it wasn’t until the arrival of the Norman Lord, John de Courcy in the 13th century when Antrim town became reshaped around the mote and bailey castle whose remains you can still see today.

Like a real world ‘Pillars of the Earth’ story, we can only imagine and the political tensions as the town was torn between the ecclesiastical and political centres. Ultimately the political won, as one account records: “In the early fourteenth century when the valuation for the Pope Nicholas Taxation was made, the rectory of Antrim was valued at a paltry five marks and vicarage at 12.”

So concludes this chronology of the site. Moving from prehistoric roots, to become a key monastic settlement, eventually falling victim to the many conflicts which plagued the island. But through it all stood this tower. So let’s turn our attention to it specifically.

What is a Round Tower?

Before considering Antrim’s specifically, it’s worth considering what round towers even were – why were they built in the first place?

The name in Irish for round tower is cloigthithe meaning “bell houses””. Bells were central to monastic life, marking the hours of prayer and summoning communities to worship. Placed high in the tower, their sound would have carried across the surrounding landscape, reinforcing the spiritual authority of the monastery.

The towers began to appear across Ireland mainly from the 10th century onwards (although Antrim may have been an earlier exception). Scholars connect their rise to the threat of Viking incursions, when monastic communities saw the value of their defensive features. Built with elevated doorways several metres above the ground, the tower could be accessed by a ladder that was then pulled up in times of danger. The thick stone walls and narrow windows further reinforced their role as places of refuge.

Storage may also have been a key function. Towers provided secure places to safeguard relics, manuscripts, liturgical objects, and treasure. In an age when wealth was easily lost to fire or plunder, the stone-built tower represented both security and permanence. Finds from excavated towers, including bones and artefacts, lend weight to this interpretation.

Yet the meaning of the tower was more than practical. Rising high above the countryside, these structures symbolised the power of the Church, the endurance of the faith, and the prestige of the monastic community. They also carried cosmological and spiritual significance: their height drew the eye heavenwards, a visual metaphor for the link between earth and the divine, much like church bell-towers.

Architecture and Features of the Antrim Round Tower

The round tower at Antrim remains visually striking even today. Standing over 28 metres in height and constructed from basalt, a stone typical of the local geology, it is an imposing and iconic sight. Like other towers across Ireland, it follows the classic tapering form: a broad circular base that narrows as it rises, topped originally with a conical cap.

One of the most distinctive features of round towers is the raised doorway, positioned several metres above ground level. At Antrim, this doorway sits around 6.5 metres up, a height consistent with defensive considerations. Access would have been by wooden ladder, which could be drawn up in times of danger. Inside, the tower was divided into several timber-floored storeys, reached by ladders or stairs, with small windows allowing light into each level. The top storey usually contained four large windows aligned with the cardinal points, a feature also visible at Antrim. These openings may have served both practical and symbolic roles: projecting the sound of bells across the countryside and marking the tower as a visible sign of Christian order in the landscape.

Its masonry demonstrates careful shaping and coursing of local basalt, a difficult material to work compared to sandstone or limestone used in many other Irish towers. This suggests a highly skilled building team and significant investment by the monastery.

Comparisons with Other Round Towers

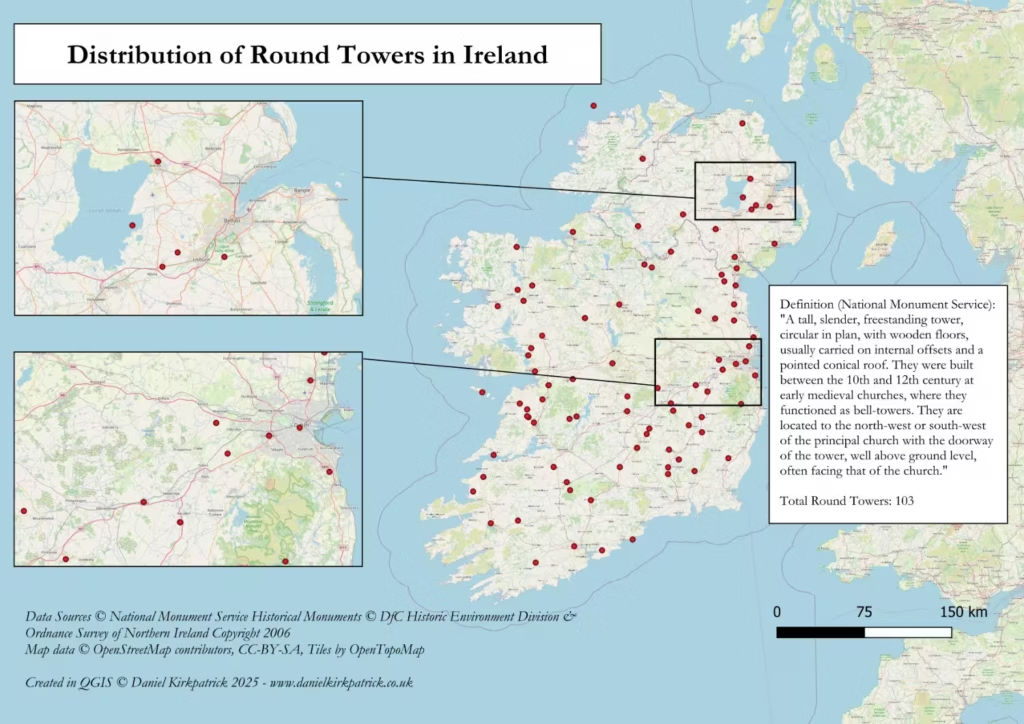

Antrim’s round tower is best understood in the wider context of Ulster’s surviving examples. With 103 recorded across the whole island, there are plenty to compare with.

Clones in County Monaghan preserves one of the best parallels to Antrim. Both towers stand to considerable height, with well-preserved masonry and elevated doorways. Clones, however, retains a more complete conical cap, offering valuable insight into how Antrim’s missing summit would once have appeared. The similarity in stonework and proportions suggests a broadly contemporary phase of construction, likely spanning the 10th to early 11th centuries.

Devenish Island in County Fermanagh provides another point of comparison. Its tower rises over thirty metres and dominates the monastic landscape, much like Antrim’s would have done in its ecclesiastical setting. Devenish’s tower is notable for its refined masonry, incorporating dressed blocks of sandstone that hint at the wealth and influence of its community. When set beside Antrim, the differences in material and finish underline the adaptability of the round tower form to local resources and monastic ambition.

Ulster also preserves more fragmentary remains, such as the base of the tower at Drumbo in County Down. While modest in scale, its survival highlights how widespread the tradition was across the north. The contrast with Antrim, which still rises impressively above the town, emphasises the remarkable preservation of the latter.

Through these comparisons, Antrim emerges as one of the most intact towers of Ulster, both in scale and in condition. It exemplifies the architectural ingenuity of early medieval monastic builders while sharing in a broader northern tradition that balanced practical needs with symbolic expression.

Legacy and Significance

The round tower at Antrim stands as a symbol of a monastic community which endured for over a millennia. It saw numerous conquests and wars, literally weathered Ireland’s history on its walls, and remains emblematic of an ancient Irish society which remains relevant today.

As you stand looking up at its piercing pinnacle, it’s difficult not to be drawn to the faith and passion which would have designed and built this pointer to heaven. Whether you have a faith or not, this is a remarkable site and one which will likely continue to inspire generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions: Antrim Round Tower

The current tower is generally dated to the 10th century, though many scholars suggest an earlier foundation connected to a local monastery dating as far back as 495AD.

Yes. The tower stands on the outskirts of Antrim’s town centre and remains freely accessible, forming part of the area’s public heritage landscape.

Round towers served as bell towers, lookouts, and places of refuge during raids. They were also symbols of monastic prestige, visible from afar. They do look amazing.

Tradition associates the site with the wider network of early Christian monasticism in Ulster, though direct links to Comgall remain uncertain.

Today, the tower stands at approximately 28 metres. While not the tallest in Ireland, its proportions and well-preserved masonry make it striking.