Standing today in the town of Bangor, the remains of Bangor Abbey offer the faintest echo of its former glory. It is difficult to imagine that this quiet site was once one of the most important centres of early medieval Christianity in the world. Founded in the sixth century, it drew students, scholars, and pilgrims, from across Ireland and beyond. In its prime, Bangor Abbey rivalled monasteries like Clonmacnoise and Armagh in prestige, commissioning missionaries who would shape the future of the Christian faith when the rest of Europe struggled through the Dark Ages.

Of course, Bangor became more than a religious settlement. For medieval Christianity wasn’t simply about the faith; it encapsulated culture, art, politics, and an entire local economy. So by understanding Bangor Abbey, we begin to develop our understanding of this early medieval period in Ireland. Therefore, this post explores the evolution of the site, from its founding to eventual decline. We consider its influence within the region, alongside its missional message throughout Europe. For Bangor was much more than a mere Abbey. It was a symbol of Ireland’s influence on the world; something which has endured down through the centuries, right up to today.

The Foundation of Bangor Abbey

According to tradition, Bangor Abbey was founded around 558 AD by St. Comgall. Born in Antrim and educated by some of the leading scholars of the day (St Finian), Comgall decided to set up his own monastery grounded in his particular reading of the bible. Like many other monastic traditions, Comgall is remembered for his deep asceticism and uncompromising vision of monastic life.

He chose the site at Bangor — the Irish Beannchar, meaning “horned curve” or “crested ridge”. Located on a strategic stretch of coastline, the choice was likely practical as well as symbolic. It also was close to what were likely a hub of other monastic communities in the region at that time, whether in Antrim or Nendrum, not to mention the centres of Downpatrick and Armagh.

It would have been a self-sufficient community, fully equipped to meet the needs of its burgeoning population of scholars. Monks would have lived in cells with their families. There would have been an oratory for worship and prayers – the daily rhythm of monastic sites. The scriptorium would have been used for writing. And there would have been an entire industry of farming, carpentry, metal-working, and tanning. For instance, there is evidence of a watermill over what is now an underground stream.

But Bangor was unique in many ways, becoming one of the greatest Monastic Schools in Europe for almost 300 years. For me, this raises natural questions for us to turn to next on: ‘what did it teach and why was it so significant?’

Bangor as a Centre of Asceticism and Learning

From its earliest days, Bangor was known for the severity of its rule. Comgall’s monastic code emphasised extremes of poverty, fasting, prayer, and silence. Accounts describe the community as enduring a life of strict discipline, sometimes to the point of harshness. Yet it was precisely this rigour that drew followers.

Comgall is said to have only permitted bread, water, and vegetables, with the exception of milk for the sick or elderly. He recited psalms while immersed in the nearby stream – anyone living in Ireland will know just how cold such streams can be. Not content to merely fast, he is said to have fasted for three days with his arms outstretched in the sign of the cross. While such acts seem extreme to us today, by Comgall and his followers they were seen as a path to holiness. The idea was that by denying human desires you could purify the soul, resist sin, and develop greater intimacy with God.

Monks flocked to Bangor not only from Ulster but also from across Ireland and even from Britain. At the point of his death, it is believed some 3,000 followers lived at Bangor. While this number is frequently repeated in medieval sources, modern scholars regard it as likely exaggerated, perhaps including monks in outlying affiliated cells rather than all resident at Bangor Abbey still. Still, the evidence makes clear that Bangor quickly rose to prominence among the great Irish monasteries, which brings us to the culture and art of the Abbey.

Bangor Antiphonary

One of the most important surviving links to this intellectual tradition is the Bangor Antiphonary, a Latin liturgical text written between 680-691AD. Though the manuscript itself was later preserved in Italy, it provides a rare glimpse of the prayer traditions and monastic culture that flourished at Bangor.

Among its contents are hymns dedicated to St. Comgall and a commemorative hymn listing the abbots of the community. Other unique texts include the Versiculi Familae Benchuir – celebrating the Bangor monastic “family” – and the Eucharistic hymn Sancti venite Christi corpus sumite – a piece not found in any other early manuscript. Alongside these, the book contains standard canticles like the Te Deum and Gloria in Excelsis, twelve metrical hymns, and a range of collects, antiphons, and evening prayers. Together these texts reveal a distinctive blend of local identity and daily prayer that defined the Irish church in the 7th century.

This would have been written in the scriptorium at Bangor by the monks. It was a key part of their training and daily practices to ensure that biblical texts, commentaries, and prayers were preserved and disseminated. This culture of careful preservation and study placed Bangor at the forefront of Irish learning, alongside monasteries such as Clonard and Clonmacnoise.

Bangor’s commitment to learning also meant that it attracted students from across Ireland and even from overseas. The very fact that the Antiphonary is now held in Milan, Italy, reinforces this point. And so we turn next to this outward facing part of the Abbey, to its mission across medieval Europe.

Missionaries from Bangor Abbey

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect of Bangor Abbey’s history is the way its influence reached far beyond Ireland’s shores. From the late sixth century onwards, Bangor produced some of the most famous missionaries of this period. Notable examples include St. Columbanus, St. Gall, and St. Malachy.

Columbanus left Bangor around 590 with a small band of monks travelling first to Gaul and then onwards to Italy. In Gaul he founded the monastery of Annegray and Luxeuill in Burgundy, but was later exiled by the King of Burgundy for offending him. Settling then in Italy, he founded the monastic community of Bobbio. Initially travelling with Columbanus was Gall who is now the patron Saint of Switzerland.

Later in the 12th century, St Malachy revived the Abbey’s declining fortunes, introducing the Augustinian order of monasticism. While not a missionary himself, he travelled across Europe and developed a particularly strong relationship with the abbot of Clairvaux in France.

Through these men – and likely many others who have been lost to history – Bangor Abbey became a spiritual seedbed for the renewal of Christian Europe. Its reach extended well beyond the shores of Belfast Lough into the forests of Gaul and the valleys of Italy.

Archaeological and Historical Evidence of Bangor Abbey

Despite its immense importance in early medieval Christianity, very little survives of Bangor Abbey’s earliest buildings. This is mainly because it would have been originally constructed from wood and other perishable materials rather than stone. So what visitors see today are mainly the remains of the later medieval abbey church, constructed long after the golden age of Bangor’s influence.

That said, archaeological excavations in 2006 and 2013 found very limited evidence of the original settlement. These included timbers dating to the 6th century, the time of the original settlement, approximately 30 skeletons, evidence of food waste and pottery, and even a lead stylus believed to have been used in writing. Aside from the antiphonary, the 9th century bronze hand bell (known now as the Bangor Bell) is likely the most significant find we have to date. This would have been used to call monks to prayer throughout the monastic daily routine.

The historical record, however, paints a clearer picture of Bangor’s prominence. The Irish annals — particularly the Annals of Ulster and the Annals of Tigernach — contain frequent references to the abbey. These include the deaths of abbots, disputes between monastic leaders, and accounts of raids. The coverage of the Abbey in these sources lead one scholar to conclude Bangor Abbey was “ranked second only to Armagh in terms of importance of the Northern Irish monasteries”.

That is, until the Vikings.

Raids and the Decline of Bangor Abbey

The wealth and prestige of Bangor Abbey inevitably made it a target throughout its history. The Annals of the Four Masters records that the church was burned in as early as 611AD, and again in 670AD. Then again it was burned on 751AD on St Patrick’s Day and “plundered by foreigners” on 822AD. The last of these references likely referred to the beginning of the Norse raids.

So it was from the late eighth century onwards, Norse raiders began attacking coastal monasteries across Ireland, seeking plunder and captives. Bangor, situated on Belfast Lough with easy access from the sea, was especially vulnerable.

Yet the abbey did not vanish entirely. Monastic life continued, though often in diminished form. By the tenth and eleventh centuries, Bangor remained a functioning ecclesiastical site but lacked the prominence it had enjoyed in earlier centuries. New centres, such as Armagh and Clonmacnoise, rose in importance, while Bangor’s reputation diminished.

The later arrival of the Normans in the late 12th century brought further change particularly under St. Malachy noted above. In the 12th century Bangor Abbey was re-established under Augustinian canons, who rebuilt parts of the complex in stone. This later phase accounts for much of the visible remains still standing today. The medieval church and tower reflect this Norman re-foundation rather than the original monastery of St. Comgall’s time.

Comparisons with Other Monastic Centres

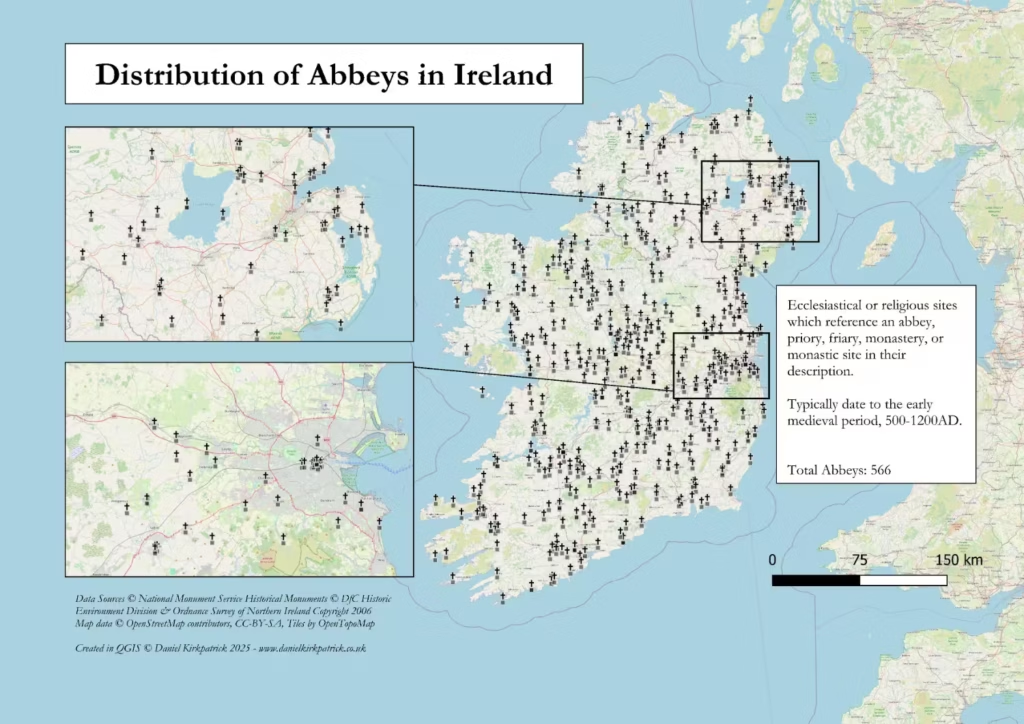

To understand Bangor Abbey’s true place in history, it is useful to set it alongside the other great monastic centres of early medieval Ireland and beyond.

Clonmacnoise, founded by St. Ciarán in the mid-sixth century, became one of the most important monastic settlements in central Ireland. Like Bangor, it produced manuscripts and fostered artistic traditions, but Clonmacnoise stood out for its monumental stone crosses and round towers, symbols of a flourishing ecclesiastical and political hub at the crossroads of Ireland’s river routes.

Armagh, associated with St. Patrick, occupied a different kind of role. As the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland, it claimed primacy over the Irish Church, exercising authority through bishops and synods. Bangor never rivalled Armagh in hierarchical power but complemented it by acting as a centre of ascetic devotion and missionary energy.

Across the sea, Iona, founded by St. Columba in 563, shared much with Bangor. Both were engines of missionary activity, sending monks to Britain and the Continent. Yet their approaches differed as Iona shaped the faith of northern Britain and became a political as well as religious power in the Gaelic world, whereas Bangor’s influence radiated more widely across Europe through the journeys of Columbanus and his companions.

By placing Bangor within this wider network, we can appreciate it not simply as a local abbey in County Down but as a key node in a transnational Christian world.

Legacy and Modern Significance of Bangor Abbey

Though centuries of upheaval transformed Bangor Abbey, its legacy still resonates in Ireland and beyond. The site remains a tangible reminder of the intellectual and spiritual energy that early Irish monasteries contributed to Europe, and its story continues to shape both local identity and wider understandings of Ireland’s Christian past.

Bangor’s reputation as a missionary powerhouse is celebrated across Europe, particularly in places linked to Columbanus, such as Luxeuil and Bobbio. Pilgrimage routes, academic conferences, and heritage collaborations continue to connect these sites, showing how the legacy of Bangor’s monks transcends modern national borders. In recent decades, initiatives such as the “Columban Way” have sought to revive interest in these historic links, promoting Bangor as a starting point for cultural and spiritual journeys.

For modern Ireland, Bangor Abbey also speaks to broader themes of resilience and continuity. Despite Viking raids, Norman re-foundation, and centuries of decline, the site never fully lost its sacred status. The persistence of Christian worship on the site for over 1,500 years makes it one of the longest continuously active religious landscapes in Ireland.

From a visitor’s perspective, Bangor Abbey remains a place where the layers of Irish history are unusually visible. Standing among its ruins, one can trace a line from the heroic age of monasticism, through medieval reconstruction, into the living parish of today. In this way, the abbey embodies both change and endurance, a symbol of how Irish Christianity adapted to new challenges.

Frequently Asked Questions: Bangor Abbey

Yes, the Irish annals record that Bangor Abbey was attacked in the early 9th century. In 823–824, Viking raiders plundered the monastery, killed clergy, and disturbed the relics of St. Comgall. These raids highlight the vulnerability of Ireland’s coastal monasteries.

St. Comgall established Bangor Abbey around 558 AD. The abbey fostered a strict ascetic lifestyle and became famous for training monks who carried Irish Christian traditions to Scotland, England, France, and beyond.

The Bangor Antiphonary, written between 680–691 AD, is a Latin liturgical manuscript from Bangor Abbey. It preserves hymns, prayers, and antiphons that provide rare insight into the devotional life of the early Irish church. Today it is kept in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan.

While little remains of the early medieval monastery, the present Bangor Abbey church stands on the original site. Visitors can explore the grounds, medieval ruins, and nearby heritage markers that commemorate its long history as a Christian centre in Ireland.