The Hill of Tara looms above the plains of County Meath as the legendary seat of Ireland’s ancient High Kings. For 5,000 years this sacred hill has inspired myths, rituals, and royal ceremonies. Today its moss-covered mounds and standing stones still draw visitors who seek the stories beneath the surface. In this guide, discover the ancient history, mythology and archaeology, of the Hill of Tara.

Historical landmarks can, in themselves, become symbols and even metaphors for an entire historical period: whether it’s the Coliseum in Rome, the Parthenon in Athens, or the Pyramids in Egypt. These sites take on a character beyond the mere stones and presence they embody, becoming immortalized in the myths, legends, and histories which surround them. For Ireland, the Hill of Tara should be counted among these. For, while the stones and great buildings of the once great palace and forts have long since disappeared, the site remains central throughout millennia of Irish history as an ancient seat of Irish kings and sacred rituals.

The Hill of Tara’s Mythological Origins

The Hill of Tara looms large in Irish mythology as the seat of the High Kings and a nexus between the human and divine. In fact, a popular saying notes that at Tara there is only a “thin veil” separating history from legend. According to medieval lore, the very name Tara (Irish Teamhair) comes from a goddess or queen named Tea who was said to be buried on the hill. This mythical origin hints that Tara was seen not just as a place, but as a personification of sovereignty itself – a landscape imbued with spirit and authority.

Little wonder that kings in legend had to literally marry the land: later stories recount pagan High Kings undergoing a ban‑feis, a ceremonial wedding to the goddess of the land, to legitimise their rule. Powerful female figures like Macha and the Morrígan exemplify this idea – warlike goddesses who embody the land’s power and who must be appeased or embraced by the would-be king. In one tale, the Morrígan (a fearsome war goddess) bestows victory or defeat on kings, demonstrating that even the mightiest warrior needed the favor of the Otherworld to rule.

Ancient History of the Hill of Tara

Echu, King of Tara, looks out over the palace’s ramparts, surveying his verdant kingdom like he did every morning. Only this time he sees a lone man walking towards him. This mysterious figure, Midre, hails the king and invites him to a game of fidchell. Rounds of gambling follow with ever increasing stakes, culminating in the King eventually being tricked into betting a kiss and embrace with his wife beautiful wife Étaín’. So goes the Irish myth ‘The Wooing of Étaín’.1

I retell this in brief as it provides a wonderful example of how Tara plays a central role throughout many ancient Irish stories. Others include the ‘Destruction of Da Derga’s Hostel’ or the famous epic ‘Cattle Raid of Cooley’ where Tara appears again and again. It was the site of the High King, the location of a famous festival, a place of judgement, politics and intrigue. And through these colourful tales, these aspects of the site are brought to life.

Tara’s Place in Mythology

The reason the High King Echu was even married to Étaín was because his vassals refused to hold a festival to a king with no queen, which is why Echu then sought out Étaín in the first place. What is truly interesting though is that the High King wanted to hold a festival of Tara “so that their taxes and assessments for the next five years might be reckoned” – the cultural event was entirely political and economic in design. Such snippets of history are woven so beautifully and subtlety into these narratives, it is easy to miss them.

So Tara was and remains central throughout the Irish mythological legacy, and for good reason.

What can you find at the Hill of Tara?

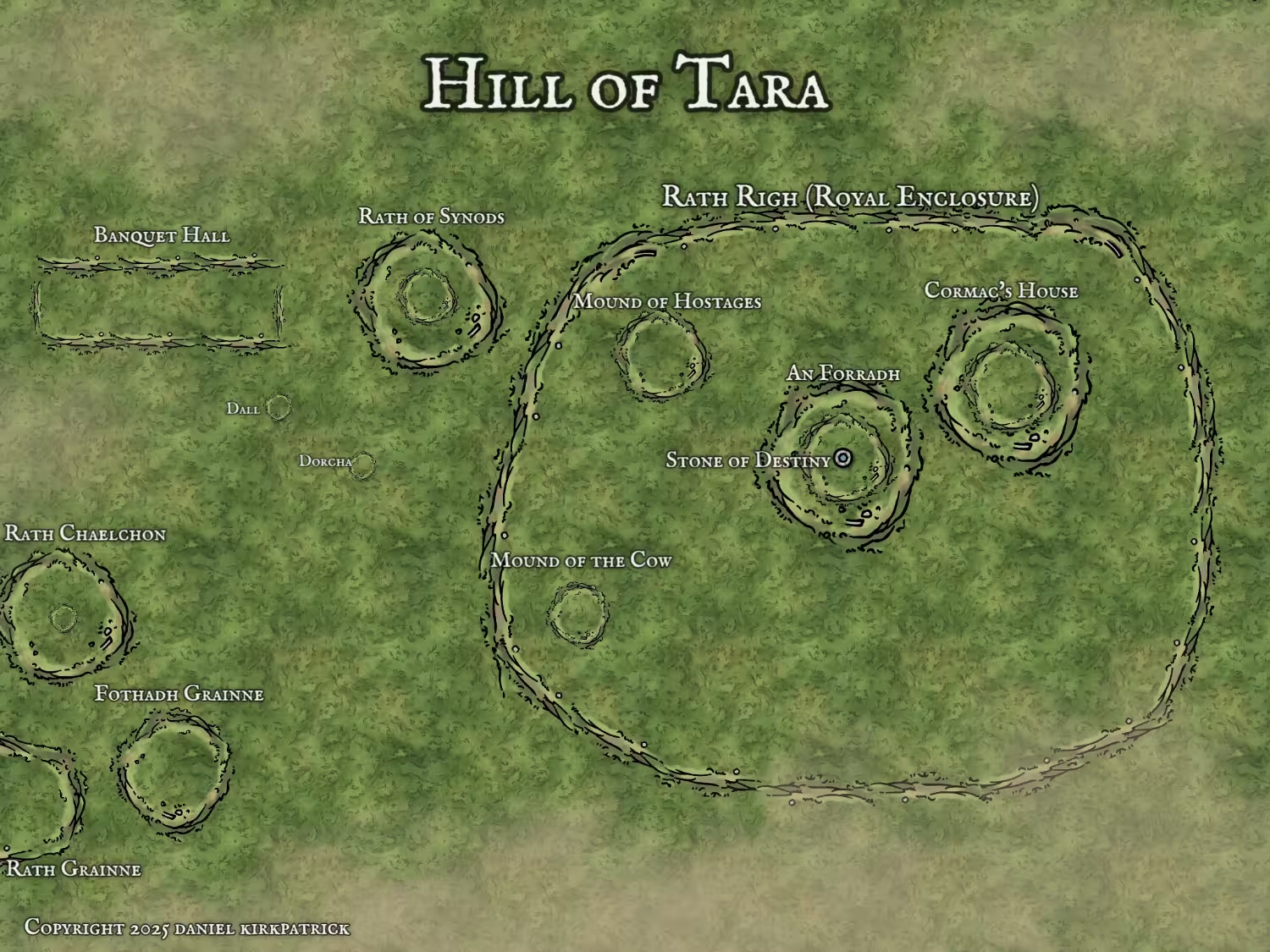

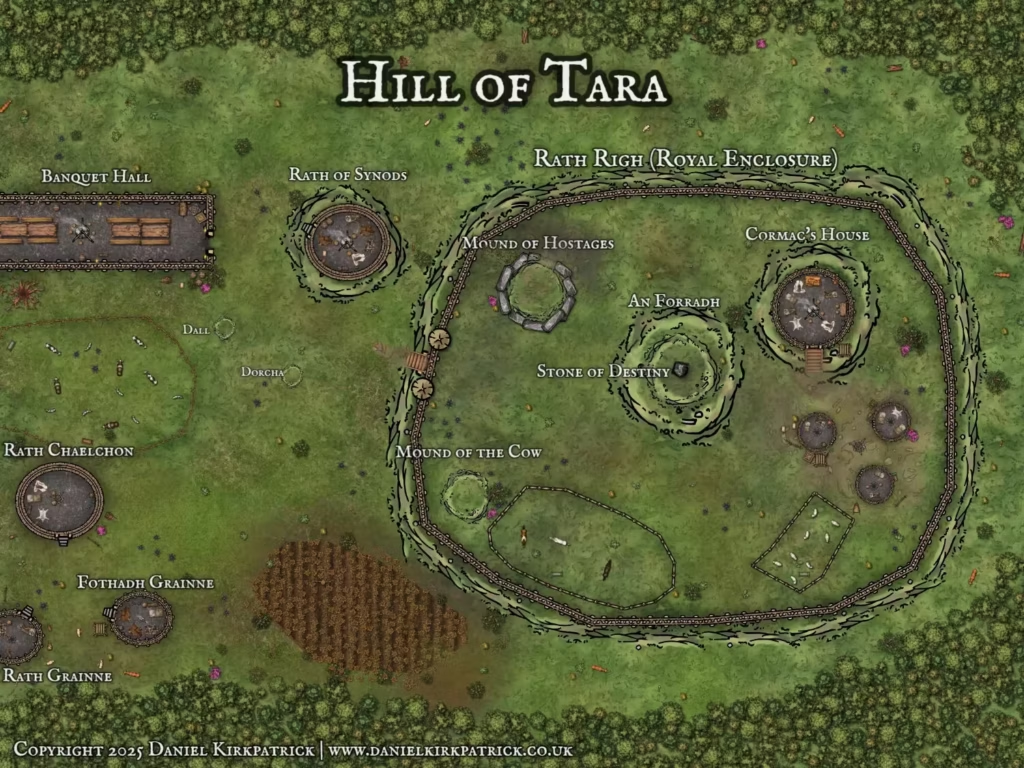

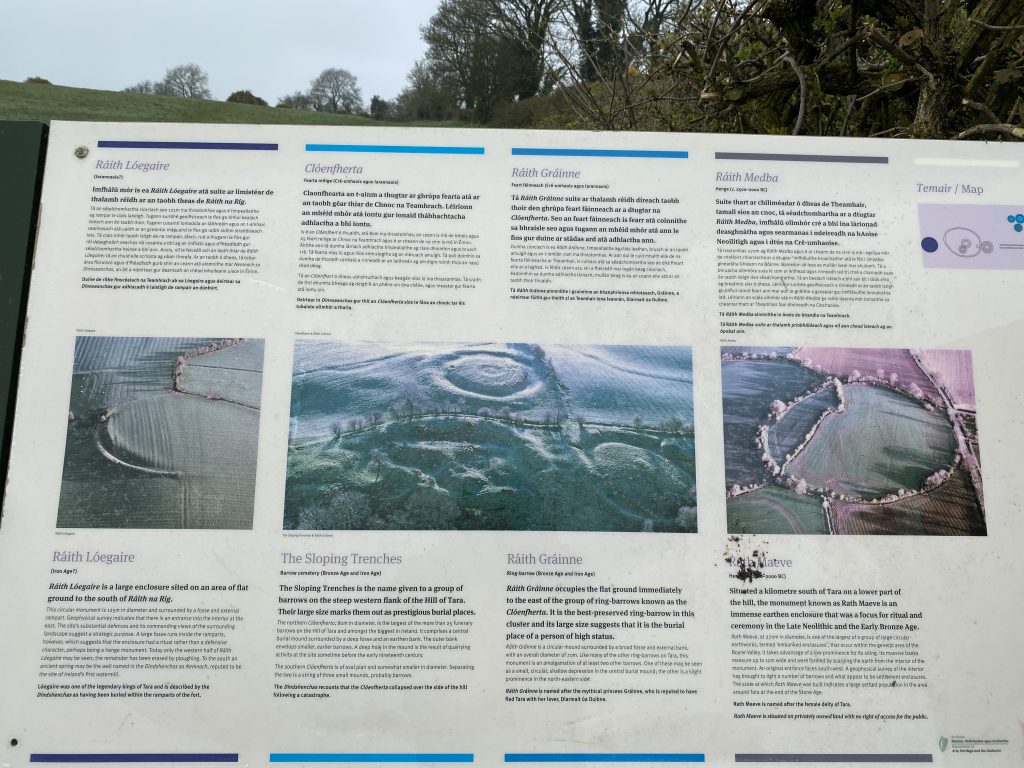

For 5,000-6,000 years Tara has remained a central part of Irish history. The oldest surviving monument on the site is the Mound of the Hostages, “a small passage tomb dating from the third millennium BC.”2 But the catalogue of historical sites is itself staggering.

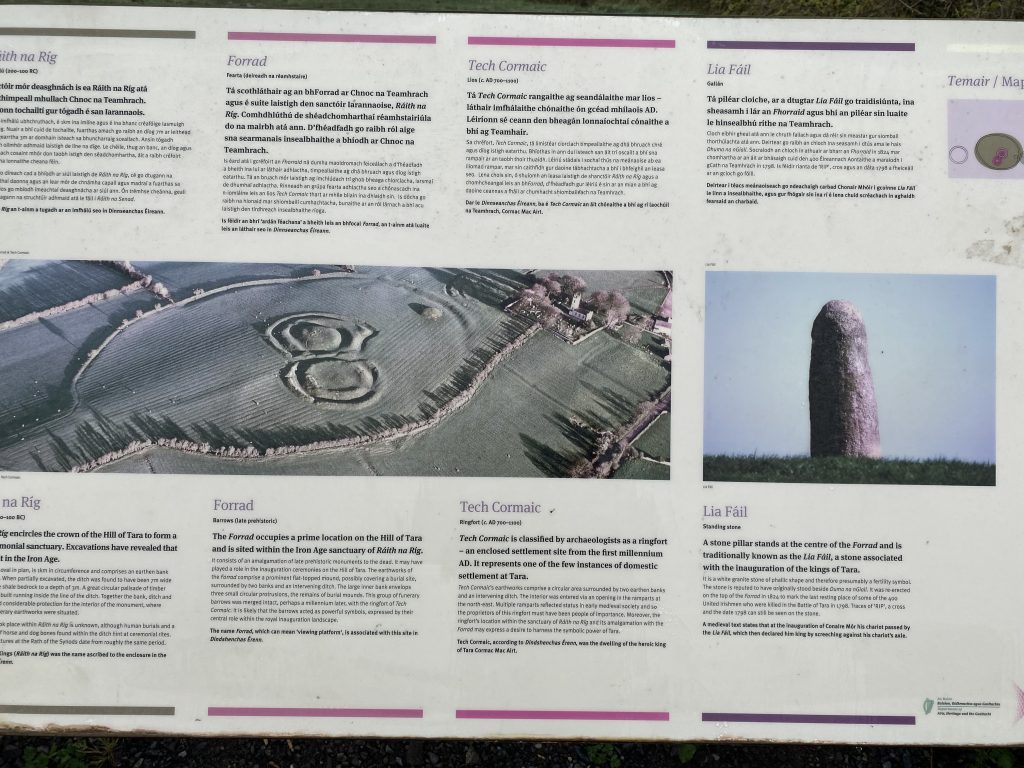

An 853 ft diameter fortification, called the Fort of the Kings, consisted of “two walls or parapets with a deep ditch between.”3 Within this huge site are two further monuments likely built much later: the bivallate ringfort called Cormac’s House (244 ft-wide) which is linked to the second mound (300 ft-wide) called the Forrad. The Forrad’s name “signifies ‘a place of public meeting’” and a ‘judgement seat,’ cognate with Latin forum”.4

Archaeological Finds at the Hill of Tara

| Feature / Artifact | Type | Date / Period |

|---|---|---|

| Mound of the Hostages (Dumha na nGiall) | Passage Tomb | Neolithic (c. 3200 BC) |

| Carrrowkeel Pots | Pottery Vessels | Neolithic (c. 3200 BC) |

| Bone and Antler Pins | Personal Ornaments | Neolithic |

| Beads and Pendants | Personal Ornaments | Neolithic |

| Battle-Axe | Weapon | Early Bronze Age (c. 1800 BC) |

| Gold Torcs | Jewelry | Early Bronze Age (c. 2000 BC) |

| Woodhenge | Timber Circle | Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age |

| Ráth na Ríogh (Fort of the Kings) | Ceremonial Enclosure | Iron Age (1st century BC) |

| Teach Chormaic (Cormac’s House) | Round Enclosure | Iron Age |

| Forradh (Royal Seat) | Burial Mound | Iron Age |

| Lia Fáil (Stone of Destiny) | Standing Stone | Iron Age |

| Ráth na Seanadh (Rath of the Synods) | Multivallate Enclosure | Iron Age to Early Christian Period |

| Roman Artifacts | Various | 1st–4th centuries AD |

| Infant Burial with Dog | Human and Animal Remains | Iron Age |

| Ráth Laoghaire (Laoghaire’s Fort) | Ringfort | Iron Age |

| Claonfhearta (Sloping Trenches) | Burial Mounds | Iron Age |

| Teach Miodhchuarta (Banqueting Hall) | Ceremonial Avenue | Iron Age |

| Rath Meave | Henge | Early Bronze Age (c. 2000–1500 BC) |

Lia Fail: Inauguration Seat of Ancient Kings

It’s on the Forrad that stands an iconic standing stone 6ft high. Generally, it is regarded as the Lia Fáil, “the inauguration stone of the Irish over-kings”, which legends say roared when presented with a king of true royal heritage.5 Legend claims this standing stone would let out a magical roar when touched by the true High King of Ireland. The Lia Fáil was even said to have been brought to Ireland by the Tuatha Dé Danann, the tribe of gods in Irish lore, as one of their four sacred treasures.6

In myth, the stone’s cry affirmed a king’s divine right – a bit like an ancient “approval rating” from the gods. One story tells of the legendary High King Conn of the Hundred Battles who, walking atop Tara at dawn, stepped on a stone that screamed so loudly it was heard across the land. The druids declared this an omen: the number of cries matched the number of Conn’s descendants destined to rule.

Through tales like theseTara earned its reputation as the inauguration place of Irish kings, where mortal rulers met the judgment of fate. However, it is believed that the stone was actually moved there in the 19th century from its original place. Regardless, the presence of such a judicial site shows just how crucial Tara would have once been to the region’s governance.

The Banqueting Hall: Ancient Cultural Centre of Ireland

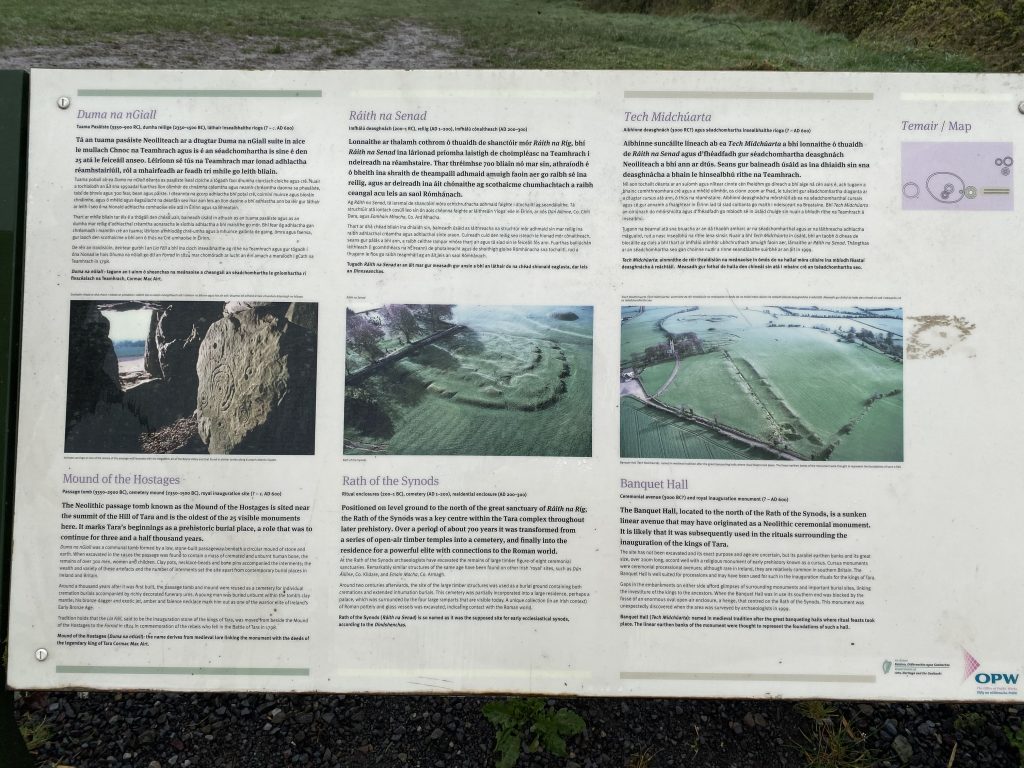

There’s also a 200-m long earthwork avenue which is what remains of the Banqueting Hall. It would have once housed a great timber building which would have reached 45 feet-high, over 750 feet-long and 45 feet-wide with over 12 different doors.7 For a modern reference point, that’s around the height of a contemporary 4-storey dwelling, and over 3,000 sq metres (the average semi-detached house in the UK has 93sqm floor area). The sheer scale of such a building is difficult to exaggerate.

Many stories set pivotal events at Samhain (the Celtic New Year around November) when the veil between worlds was believed to grow thin. It was at Samhain, tales say, that the feasts of Tara (Feis Temro) were held, drawing warriors, bards, and druids to convene under the High King’s aegis. At these great gatherings, laws were proclaimed and stories exchanged in an atmosphere of both revelry and ritual – imagine a combination of parliament session and harvest festival. In effect, the Feis of Tara functioned as a grand assembly “like a parliament” where every third Samhain the chiefs and sages of Ireland met to pass laws and settle affairs.

Through such depictions, Tara lives in myth as Ireland’s centre. In fact, tradition holds that five ancient roadways radiated from Tara to the far corners of Ireland, linking the High King’s seat to each province. But this goes back much further than the Iron Age.

Who’s buried at the Hill of Tara?

The oldest visible monument at Tara is the Mound of the Hostages (Dumha na nGiall in Irish), a small grassy mound with a stone passage entrance. This is actually a Neolithic passage tomb built over 5,000 years ago (around 3200 BC). When excavated in the 1950s, the remains of over 300 individuals were found inside or around the chamber, spanning centuries of use from c.3400–1600 BC. Many of these were cremations placed in urns, accompanied by beads and bone pins. The very last burial inserted into the mound was a young teenage boy, laid to rest with a necklace of exotic stone beads. Even after its primary use as a tomb, this mound remained important: Bronze Age people (c.1500 BC) continued to inter their dead in its earthen cap.

To this day the Mound of the Hostages stands as a quiet knoll. Its carved stone entrance is oriented to catch the first light of the rising sun at certain times of year (Samhain and Imbolc). It is a humbling thought that when the legendary High Kings of later eras walked Tara, that mossy mound was already older to them than the pyramids are to us.

Separating worlds: Fort of the Kings

Moving forward in time, Tara’s most intensive activity seems to date to the Iron Age (roughly 600 BC – 400 AD). One monument dominates the hilltop: the Ráith na Rí or “Fort of the Kings,” an enormous oval enclosure about 1 kilometer in circumference. This earthwork was built around 100 BC. And it consists of a broad ditch ringed by an outer bank, and likely would have had a wooden palisade.

Despite the name, Ráith na Rí doesn’t resemble a defensive fortification. Curiously, the ditch’s bank is on the outside (the reverse of a normal fort). This implies it was symbolic or ceremonial rather than military. Indeed, archaeologists discovered human and animal burials within the ditch, including the poignant find of an infant buried alongside a dog, perhaps as a spiritual guardian for the child’s journey. Such deposits sound more like ritual offerings than the trappings of warfare. We might imagine that the very perimeter of Tara was sanctified ground. This was where graves and sacrifices marked the boundary between the sacred hill and the outside world.

Medieval evolution of The Hill of Tara

Scattered around Tara are dozens more archaeological features – over 25 ring-barrows and earth ring ditches from various periods. Each of these was likely a burial or ceremonial site. One, called the Sloping Trenches, is a mysterious set of linear ditches whose purpose is still unknown. Another prominent feature is the Rath na Seanadh (Rath of the Synods), a multi-ringed enclosure near the current churchyard. Its name links it to early Christian synods or meetings of churchmen. Indeed it has yielded high-status Roman artefacts like fine imported pottery and glassware.

The presence of luxury goods from Roman Britain shows that Tara’s Iron Age/Early Medieval elites had far-reaching connections. The High King’s table was apparently stocked with the best wine and tableware the wider world could offer.

But hopefully the point has been well made, that even to use the term ‘Hill of Tara’ is misleading. This is no mere hill. It’s a veritable hotch-podge of historical landmarks all concentrated together; a kaleidoscope of Irish history through the centuries.

Hill of Tara in Modern Irish Culture

Given its mythological roots, it will be no surprise that the ancient site has inspired some of the greatest Irish poets and writers. From the 19th century poet Thomas Moore who wrote his poem ‘The Harp That Once Through Tara’s Halls’,8 to W.B. Yeats’ who wrote his poem ‘In Tara’s Hall’ portraying an aging king wishing to die.9 A television documentary in 2008 notably explained: “For over 5000 years this hill in Meath has been fought over, sung of and died for.”10

The Nobel prize winning poet, Seamus Heaney, sums it up well when he describes Tara as: “a source and a guarantee of something old in the country and something that gives the country its distinctive spirit”. The understandable public furor and outrage at the Irish Government’s proposed motorway near the site show just how powerful it remains as a symbol of culture and identity.

And yet, if you are like me and make a visit to this inspirational site of historical and mythological significance, I suspect you will be surprised by what you discover.

Visiting Tara Today

The rain pounded against our little car as we drove up the narrow, winding roads to Tara. But poor weather couldn’t deter me, nor the bleak visibility. I was too excited. After months of reading and visualising what I’d find, I was never going to turn back.

But after I arrived and drudged up the path to the entrance, it became clear very quickly that reality would fall far short of my expectation.

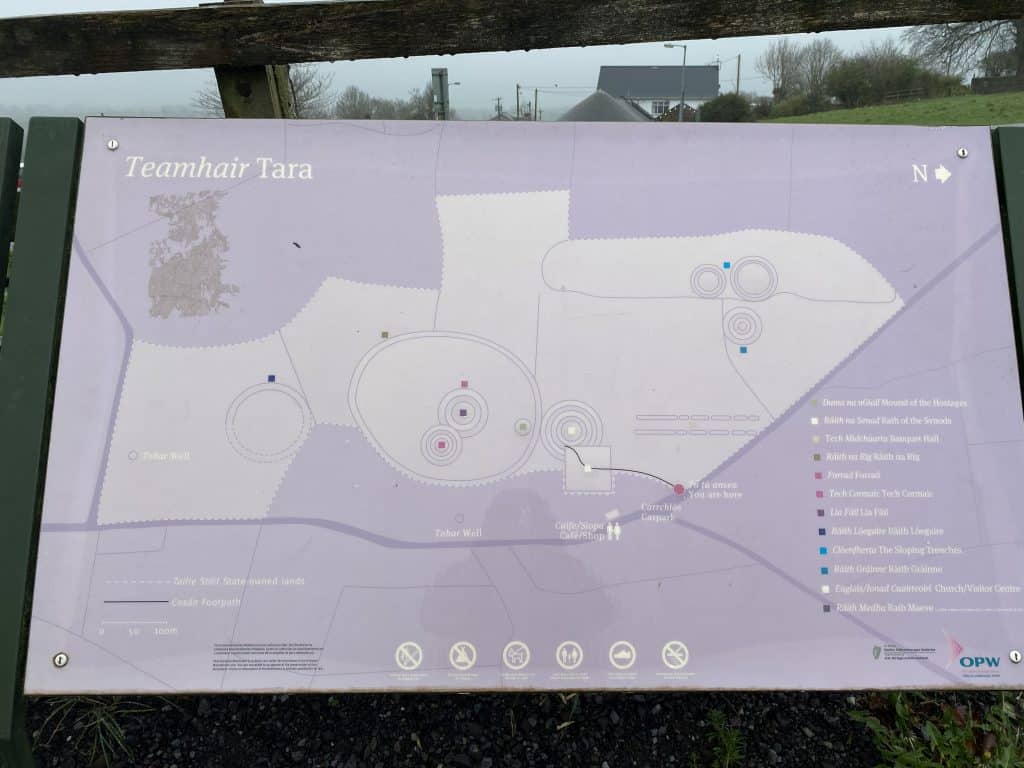

Having studied the information panels, I soon found myself lost trying to navigate the large site. To the general visitor, I confess it appeared unremarkable – mere mounds and ditches. Signage was poor. Paths non-existent. All of the sites and markers I’ve described are there, but with little to note their presence. Dog-walkers mingle with confused visitors.

As I left deflated, I couldn’t help but wonder why such a central site of national importance had been so neglected.

The Hill of Tara’s Future

Any one of the above features – history, culture, or mythology – would alone justify far better care for this site. I don’t know all the background to why this is not the case, only that surely more could be done. The brilliant examples of other sites like Fort Navan or Newgrange, show what is possible.

As someone who loves Irish history, I was surprised about how deeply this visit impacted me. To be so excited and then disappointed in such a powerful way is painful, an experience I’m sure I’m not alone in enduring.

Thankfully time heals most wounds, even those to our identity. I’ve embraced the Tara of history, of these wonderful stories and poems. I hope that one-day my passion will be shared by those who get to visit this site too.

Tips and Advice for Visitors

The Hill of Tara is located in County Meath, about 40 minutes northwest of Dublin. It is best reached by car. It’s situated just off the R147 between Dunshaughlin and Navan, with free parking available near the visitor centre.

The site is open year-round, with no admission fee to walk the grounds. The Tara Visitor Centre is housed in the former church at the foot of the hill. It offers seasonal exhibitions, a small café, and guided tours (April to September). Guided walking tours are highly recommended to gain insight into the site’s archaeological and mythological significance.

The terrain is grassy and uneven, so sturdy footwear is advised. The area is exposed, so dress for the weather. Key landmarks like the Lia Fáil, Mound of the Hostages, and Banqueting Hall are accessible on foot and signposted.

To make the most of your visit, consider combining Tara with a stop at the nearby Trim Castle or Newgrange. Sunrise and sunset are particularly atmospheric times to explore this ancient royal site. For more information, check the Meath Heritage website or local tourism offices.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Hill of Tara

It was the ceremonial seat of the High Kings of Ireland, a site of pagan ritual, and mythologically tied to the Tuatha Dé Danann.

Legend says many High Kings were inaugurated here by the Lia Fáil, the Stone of Destiny, which would roar when touched by a true king.

Yes. The Mound of the Hostages is a Neolithic passage tomb, and the site contains numerous burial mounds dating back over 5,000 years.

The Lia Fáil, or “Stone of Destiny,” is a standing stone on Tara’s summit. It was believed to roar or cry out when touched by the rightful king during inauguration. Some legends connect it to the Tuatha Dé Danann, who brought it from the Otherworld.

Despite its name, the “Banqueting Hall” is likely a processional or ceremonial avenue, possibly used during inauguration rituals. Its parallel banks and alignment suggest a formal approach route into the sacred enclosure, not a literal feasting site.

- Gantz, Jeffrey. Early Irish Myths and Sagas. London: Penguin Books, 1981. Pages 52-59 ↩︎

- Rountree, Kathryn, Tara, the M3 and the Celtic Tiger: Contesting Cultural Heritage, Identity, and a

Sacred Landscape in Ireland, Journal of Anthropological Research , WINTER 2012, Vol. 68, No. 4, p523) ↩︎ - Joyce, P.W. A smaller social history of ancient Ireland. Dodo Press, 1901. p243 ↩︎

- Joyce, p243 ↩︎

- Joyce, p244 ↩︎

- The other three magical treasures were the Sword of Nuadu, the Spear of Lugh, and the Cauldron of the Dagda. ↩︎

- Joyce, p245 ↩︎

- For the full poem see: https://allpoetry.com/The-Harp-That-Once-Through-Tara’s-Halls ↩︎

- Yeats, W.B., The Collected Poems of W.B. Yeats. Wordsworth Poetry Library: Herefordshire, 2008. Page 281. ↩︎

- Quoted in Kathryn, p523. ↩︎

![Dun Ailinne Excavation Photograph. Hamish Forbes. Notebook East Area 1975 Book 3 Hamish Forbes Field Notes. Text [Type]. Digital Repository of Ireland (2024) [Publisher]. https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.ns06j259](https://www.danielkirkpatrick.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Dun-Ailinne-Exacation-Photograph-120x120.jpg)