Perched above the roaring Atlantic, Dunseverick Castle looks out from a lonely headland that once ruled half of Ireland. Today only fragments remain, but behind them lies a story of kings, saints, and sea raiders that shaped the history of Ulster. Now a National Trust site, all that remains are but a few stone walls displaced along a small headland – a fitting metaphor for its history too. For few know of its incredible significance within Irish history. But history, when understood properly, is like a gripping thriller. Each page we turn, we get a step closer to the plot’s climax. And with the history of Dunseverick Castle, this couldn’t be truer.

This post will consider the ancient Bronze Age history of the site, charting how it evolved into an Iron Age maritime fortress of Dal Riata, a religious site associated with St. Patrick, a Medieval frontier fort, and its eventual destruction.

Bronze Age beginnings

The castle we see today is only the latest of many structures which have inhabited the site. For, according to the Annals of Clonmacnoise, the first castle was founded by none other than Sobhairce, who ruled Ireland with his brother Cermna Finn. The brothers were the first Ulster Kings to rule the entire land of Ireland, dividing the land between them. Cermna ruled the south from Dun Cermna believed to be Kinsale, Cork. Whereas Sobhairce ruled the north from none other than Dunseverick, Antrim. That’s right, there was a time when half of Ireland was ruled from this little rock which has descended into relative obscurity. Indeed, the name Dunseverick is an anglisicsed form of the original Dunsobairce (Fortress of Sobhairce).

As described by the Annals of Clonmacnoise:

“Cearmna finn and his Brother Sovarke the sonns of Ebrick m’Ire were the first kings of Ireland that euer Raigned of the house of Ulster. They Divided the whole kingdome amongst themselves in 2 parts. One of them Dwelt in Doncearmna, the other at Donsovarke; the one was king of the south, and the other king of the north.”1

Dating the brothers’ reign has been fraught with conjecture, ranging from 1155-1115BC to 1533-1493BC. But it can be assumed to have been well within the Irish Late Bronze Age. This period “saw the introduction and manufacture of a much larger range of explicit weapons” which “suggests a much more formally militaristic attitude”.2 Indeed, Sobhairce is said to have been killed in this maritime fortress by Eochaidh Echehenn, King of the sea pirates, after 40 years of rule.3

Whether or not Sobhairce himself was a real person, the Bronze Age beginning of Dunseverick’s story underlines one point clearly: this site was regarded in Irish tradition as an ancient seat of kings. Archaeological finds along the coastline reinforce this view with multiple Bronze Age sites located nearby. For a full list of these you can see my historical map of the region.

Iron Age centre of power

We will all be familiar with the old adage of ‘there’s no smoke without fire’. But equally true would be ‘there’s no road without a destination’. Five great royal roads were once built across Ireland. And – as it would have been notoriously difficult to travel with dense woodland, bogland, and predators – these roads served a vital trade and communication network across the land. They connected Tara in Meath with “the political centres of gravity of the other four provinces”, with one terminating at Dunseverick.4 Believed to date to around 100AD5, this strongly suggests that Dunseverick remained a key site of political power for the entire first millennia BC, through to the Iron Age.6

Moreover, in the Irish mythological saga, the Ulster Cycle, Dunseverick is referred to as the home of Conall Cearnach, “one of the most famous athletes of the Irish heroic cycles”.7 Conall features as a central main protagonists throughout the many myths alongside the famed warrior Cu Chulainn. Placing his home as Dunseverick strongly reinforces the cultural and political significance the site would have embodied within this Iron Age period.

Later, it is believed that in the 5th century St. Patrick blessed a well at the site. He also attributed with baptising a local man, Olcán, who would later become Bishop of Ireland.8 Archaeological efforts to identify the well remain inconclusive, but it is believed to be “to the west of the castle”.9 Though the stone St. Patrick sat on has long since disappeared. Regardless, this suggests that Dunseverick had an early Christian community or at least a notable convert.

Kingdom of Dalriada

By the early medieval period (around the 5th to 7th centuries AD), Dunseverick found itself at the heart of a trans-Irish-Sea kingdom: the realm of Dál Riada (also spelled Dalriada). This was a Gaelic kingdom that uniquely straddled two shores, encompassing the north-eastern corner of Ireland (parts of Antrim) and parts of western Scotland (Argyll and the Hebrides). Dunseverick, positioned on Ulster’s north coast facing the Scottish isles, was ideally situated as a royal stronghold of Dál Riada.

With shifting political alliances and borders, the royal site eventually shifted to Rathmore near Antrim. But Dunseverick remained a key frontier fort guarding the northern coastline and the valuable sea routes this represented.

Lia Fáil & Dunseverick

One notable king during this period was Fergus Mór mac Eirc – also known as Fergus the Great. In the 6th century, Fergus Mór famously expanded his dominion across the sea. He was actually a great-uncle of the High King of Ireland at the time (his brother Muircheartach/Murtagh mac Eirc was High King). This highlights the dynastic ties between Irish and Scottish Gaelic nobility. According to legend, around the year 500 AD Fergus sailed from Dunseverick with an entourage to claim territory in Alba (Scotland), effectively founding the Scottish branch of the kingdom of Dál Riada.

In doing so, one story recounts that Fergus brought with him the Lia Fáil, Ireland’s sacred Stone of Destiny on which High Kings were traditionally crowned at Tara. Supposedly, his brother (the High King) lent him this stone for his coronation as king in Scotland. Thus, Dunseverick Castle is romantically cast as the departure point of the Lia Fáil from Ireland to Scotland. The stone, by legend, was installed at the hill of Scone as Scotland’s coronation stone and later taken to England. But whether the stone at Scone was truly the Lia Fáil of Tara is a matter of debate. Legend aside, the Lia Fáil tale underscores Dunseverick’s stature in the early medieval imagination. It was a launching pad for kings and the sacred symbols of their authority.

Dunseverick, Christianity, and the Vikings

As part of Dál Riada, Dunseverick would have been involved in the vibrant exchange of people and culture between Ireland and Scotland in this period. Dál Riada played a pivotal role in the spread of Christianity – notably, St. Columba (Colm Cille), a monk with royal blood from the north of Ireland, traveled from Dál Riada’s Irish lands to found the monastery of Iona in 563 AD under the patronage of the Dál Riada kings. We can imagine monks and warriors alike passing through Dunseverick as they voyaged across the channel.

The prosperity of Dál Riada in Ulster did not last forever. By the 8th and 9th centuries, the kingdom was under strain. Rivals such as the expanding Uí Néill dynasty pressed in from the south, and new foes appeared from the sea – the Vikings. In 870 AD, annals record that Dunseverick (among other sites) was attacked and plundered by Viking raiders. Again in 924 AD, a raid by “Danes” (Norse Vikings in Ireland) left Dunseverick ravaged.

Decline of Dunseverick Castle

Some historians suggest that the 9th-century assaults on Dunseverick may have been aided or coordinated with rival Irish factions – for instance, the Cenél nEógain (ancestors of the later O’Neill family) might have aligned with Vikings to strike at coastal strongholds like this. In any case, these repeated attacks would have greatly weakened the power base at Dunseverick.

After these onslaughts, Dún Sobhairce begins to fade from prominence in historical records. The Gaelic kingdom of Dál Riada effectively fragmented: the Scottish portion evolved into the burgeoning Kingdom of Alba (Scotland), while in Ireland the remnants of Dál Riada’s territory were absorbed by other local powers. By the 10th and 11th centuries, the area around Dunseverick likely fell under the influence of the O’Catháin (O’Cahan) clan (related to the Cenél nEógain) or other regional overlords. Still, as a strong defensive site with rich lands nearby, Dunseverick would not have been abandoned – it remained a prize to be claimed by whoever could hold it. The stage was set for new conflicts and new castle builders in the medieval era.

Dunseverick’s Medieval History

In the Norman period (late 12th–13th centuries), the Earldom of Ulster was established by Anglo-Norman conquerors. While Norman control in the far north coast was tenuous, they did recognise key strategic sites. Dunseverick was utilised as a manorial base by the Earls of Ulster (notably the de Courcy/de Lacy and later de Burgh families who held the earldom in the 13th and early 14th centuries). This suggests the Normans maintained some presence or garrison at Dunseverick as part of their network of control – even if they did not build a massive castle there, they would have appreciated the defensive value of the existing fort.

The situation shifted after 1333, when the last de Burgh Earl of Ulster was assassinated and Norman authority in Ulster collapsed. Irish Gaelic clans rose to reclaim lost ground. Through the 14th and 15th centuries, north Antrim (including Dunseverick) became a contested zone among local dynasties. Eventually a family known as the MacQuillans (Mac Uílhíollain) emerged as the dominant force. They were descendants of a Norman family (Savages or de Mandevilles) who had become thoroughly Gaelicised. The MacQuillans ruled the territory called the Route10 and held several strongholds in the region. By the 1400s, Dunseverick Castle was counted among their possessions.

Dunseverick Castle’s Medieval Revival

Around the same era, the O’Cahans of Derry (Cenél nEógain stock) also extended their influence toward the Causeway Coast. Some accounts claim the O’Cahan clan built or significantly rebuilt Dunseverick Castle during the late 1500s. It’s possible that an O’Cahan chieftain, acting as a tributary or ally to the MacQuillans, was responsible for constructing the sturdier stone gatehouse tower whose ruins we see today. However, politically, the O’Cahans’ hold on this area was soon overshadowed by an even more powerful incoming force – the MacDonnells.

The MacDonnell family, padrt of the Scottish Clan Donald, established themselves in Antrim in the early-to-mid 16th century. Led by figures like Sorley Boy MacDonnell, they aggressively contested the MacQuillans for control of the Route. After a series of fierce battles (including the Battle of Orra in the 1550s), the MacDonnells defeated the MacQuillans and took over their lands. By around 1560, Dunseverick Castle had thus passed into MacDonnell hands. It became one of a chain of coastal castles the MacDonnells commanded – along with Dunluce Castle (their new principal seat), Kinbane Castle, and others stretching along the Antrim coast.

The Castle: Medieval Design and Fortification

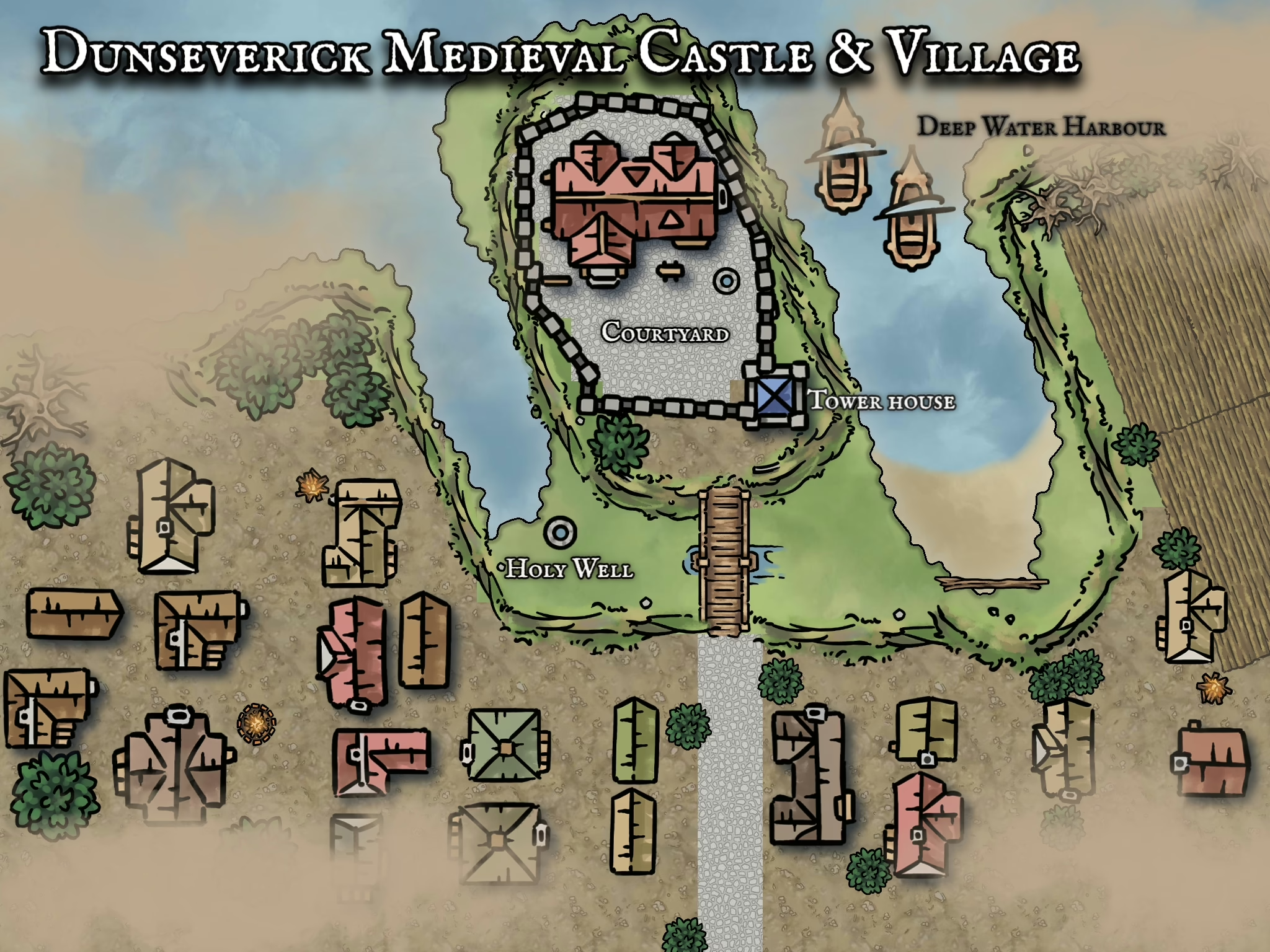

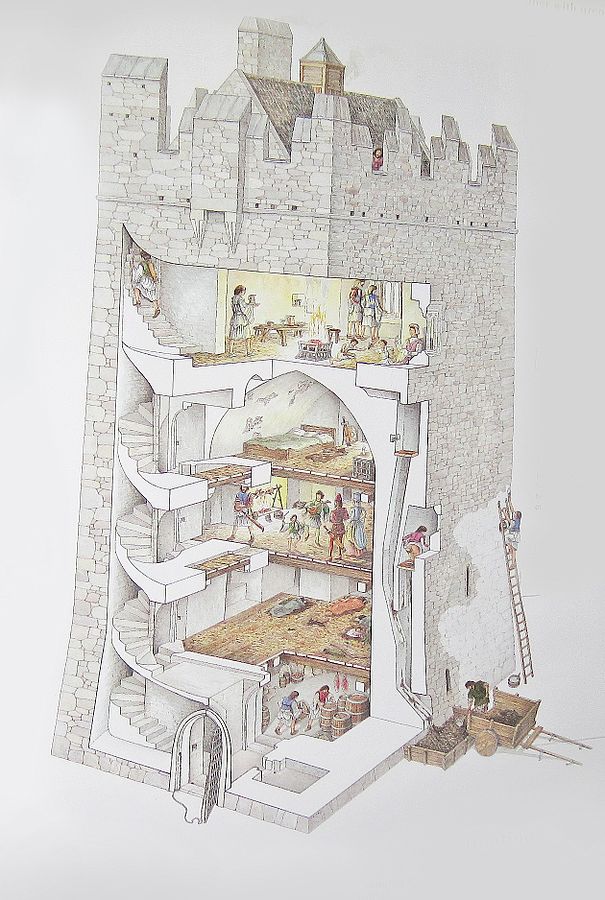

Given its position in the north of Ulster, the castle would have been closely “modelled on the coastal castles of the Scottish Highlands”, typically being “on a promontory across which a trench may be cut for protective isolation.”11 During this medieval period, the castle would have therefore likely reflected the design of the tower houses. A clear description of which is provided by the historian Jonathan Bardon:

“Typically, the tower house in Ulster…was a single tall keep, at least twelve metres high, with two towers flanking the main entrance. The dimly lit ground floor was the storeroom, with a semi-circular barrel-vault roof, temporarily supported by woven wicker mats until the mortar had set. The upper storeys were reached by a narrow winding staircase up one of the towers, lit by arrow slits; food was cooked in braziers on the first floor and taken to the banqueting hall above; and the lord slept on the uppermost storey under a gable roof shingled with oak. Most Ulster tower houses had cells, built-in latrines, window seats, secret chambers, and a bold arch connecting the two flanking towers; here there was a ‘murder hole’ for shooting at – or pouring boiling water on – assailants attempting to ram the door below.”12

Dunseverick’s natural defenses were also fully exploited. A deep trench exists across the neck of the headland, effectively isolating the castle rock from the mainland. This ditch, possibly once crossed by a drawbridge or wooden bridge, forced any attacker to approach via a narrow land bridge under the guns (or bows) of the defenders. The outline of this trench is still faintly visible on the site today.

Around the base of the tower, a bawn or courtyard would have been enclosed by a defensive wall. Within this courtyard, ancillary structures – stables, kitchens, storage sheds, maybe a forge – would support the castle’s occupants. By the 16th century, a small village or cluster of huts existed near Dunseverick. This indicates a community lived under the castle’s protection. In later times, traces of cobbled pathways and stone footings for buildings were noted around the site.

Timeline of the History of Dunseverick Castle

| Time Period | Role of Dunseverick Castle |

|---|---|

| Bronze Age (c. 1500 BC) | Legendary founding as Dún Sobhairce by King Sobhairce, marking it as a prime seat of power ruling the northern half of Ireland (in myth). |

| Iron Age (c. 100 BC – 100 AD) | Northern terminus of the Slige Midluachra (royal road from Tara), indicating status as a major Ulster power centre and trade hub. |

| Heroic Era (legendary) | Fabled home of Conall Cernach, champion of Ulster’s Red Branch Knights – showcasing its cultural and military significance in legend. |

| 5th century AD | Visited by St. Patrick, who baptises Olcán at Dunseverick – demonstrating the site’s prominence in the early Christian landscape of Ulster. |

| 6th century AD | Key site in the Kingdom of Dál Riada; King Fergus Mór reigns here before expanding to Scotland (legendary departure of the Lia Fáil from here) – making Dunseverick a bridge between Ireland and Scotland. |

| 9th–10th centuries AD | Target of Viking raids (870 and 924 AD), which underscores its continued wealth/strategic value in the early medieval period. |

| 13th–14th centuries | Incorporated into the Anglo-Norman Earldom of Ulster, then contested after 1333 – a frontier post between Norman and Gaelic spheres. |

| 15th century | Stronghold of the MacQuillan Lords of the Route – part of a chain of castles securing north-coastal Ulster. |

| 16th century | Prize in clan wars; seized by the MacDonnells (c. 1560) – used to consolidate MacDonnell control of Antrim and as a defence against incursions (English or rival Gaelic). |

| 1642 (17th century) | Destroyed by Munro’s Scots during the Confederate Wars – considered strategically enough to deny its use to Irish rebels or Scottish Catholic allies. |

| After 1650 | Strategically obsolete in the era of centralized power and artillery; left as a ruin, symbolizing the end of the Gaelic stronghold era. |

Decline and destruction

It was only then in 1642 that Dunseverick’s political significance would be closed once and for all. Following the Ulster rebellion which began in 1641, the castle was destroyed by Major-General Robert Munro and his army of Scots. Ireland was engulfed in conflict during the 1641 rebellion and the ensuing Wars of the Three Kingdoms, which in Ireland became the Irish Confederate Wars.13 In Ulster, the MacDonnells of Antrim (then led by Randal MacDonnell, Earl of Antrim) were Catholics and initially involved in the uprising against British rule. By 1642, the British Parliament had dispatched a Scottish Covenanter army to Ulster to crush the rebellion and protect Protestant settlers.

General Robert Munro, commanding these Scottish forces, targeted strongholds that could serve as rebel bases or refuges. Dunseverick Castle – still held by the MacDonnell clan or their allies – was one such target. In 1642 Munro’s troops arrived and laid waste to Dunseverick, effectively dismantling its defenses and rendering it militarily useless. Contemporary accounts note that in East Ulster the Scots “slighted” many castles (meaning they deliberately damaged them to prevent their use by the enemy). At Dunseverick, this likely meant breaking down walls, burning wooden roofs and interiors, and perhaps even using gunpowder to breach parts of the structure.

Dunseverick’s destruction in 1642 marked the close of its long chapter as an active fortress. However, the turbulence of the mid-1600s did not end there. A few years later, Oliver Cromwell’s Parliamentarian army invaded Ireland (1649–1653). In Ulster, additional Parliamentarian forces under commanders like Colonel John Venables advanced through Antrim in the early 1650s. Any stronghold that might still have been defensible – including ruined Dunseverick – was further neutralized. Local lore suggests Cromwellian soldiers visited Dunseverick and may have toppled whatever Munro left standing, to ensure it could never be garrisoned again.

Dunseverick today

If you were to travel to Dunseverick castle today, you will only see the ruins of the gatehouse that was likely built during the late Medieval period. All else has faded away with the passing of time. But, that said, it still presents a wonderfully imposing site particularly given its striking setting along the rugged Antrim coastline.

As you walk amongst these stones, you can begin to imagine the millennia of history which has it seen. Warriors, priests, Viking invaders, medieval knights, druids and kings, have all graced the same steps you take. That’s the beauty of such sites. Like the glint of buried treasure just peaking out of the earth, it gives us the glimpse into a wealth of history we can barely grasp.

I hope you get to enjoy it as I have many times before and, perhaps, this post will help bring its history to life a little more.

Frequently Asked Questions: Dunseverick Castle

Dunseverick Castle is situated on the north coast of County Antrim, Northern Ireland, near the Giant’s Causeway. It occupies a dramatic promontory overlooking the Atlantic Ocean.

Its origins are unclear, but the site was likely fortified in the early medieval period. According to tradition, it was associated with Fergus Mór and the Dalriadan kings, and may have had earlier significance during the Iron Age.

Yes. Local tradition claims that St Patrick visited Dunseverick and baptised a local chieftain named Olcán, who later became a bishop. The castle thus holds both Christian and pre-Christian historical resonance.

The castle was besieged and destroyed in 1642 during the wars of the Three Kingdoms. Today, only one ruined gate tower remains visible on the headland.

Yes. While much of the structure is lost, the site is publicly accessible. It offers scenic views and is a stop on the Causeway Coastal Route, just a short distance from the Giant’s Causeway.

- https://archive.org/stream/annalsofclonmacn00mage/annalsofclonmacn00mage_djvu.txt ↩︎

- Flanagan, Lawrence (1998) Ancient Ireland: Life Before the Celts, Palgrave Macmillan. Page 161. ↩︎

- Getty, J., 1833. Dunseverick Castle. The Dublin Penny Journal, 1(46), p362. ↩︎

- Hamilton, G. E. (1913). The Northern Road from Tara. The Journal of the Royal Society of Antiquaries of Ireland, 3(4), 310–313. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25514310. Page 310. ↩︎

- Lawlor, H. C. (1938). An Ancient Route: The Slighe Miodhluachra in Ulaidh. Ulster Journal of Archaeology, 1, 3–6. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20627196 ↩︎

- It’s important to note the original dates of the site are highly unreliable, and likely exaggerated. But, even still, it is probable the site was first inhabited in the Irish Bronze Age and enjoyed a remarkably long tenure as a political centre of power spanning centuries of ancient Irish history. ↩︎

- Hayward, R. (1938). In Praise of Ulster. Iran: A. Barker. Page 111. ↩︎

- Getty, 1833: 362. ↩︎

- Hayward, 1939:111 ↩︎

- An Anglicisation of an Rúta, referring to this stretch of north coast. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- John Bardon (2005) A history of Ulster. Blackstaff Press. Page 66. ↩︎

- For more see Bardon, 2005:136-147 ↩︎