As you walk around any modern city, nearly always your eyes will be drawn to the architecture. The style, scale, and shape of the buildings captures our attention, eliciting emotions and leaving an enduring impression. I have had the privilege of visiting many cities around the world and invariably it’s the government buildings which standout. Whether the Houses of Parliament in London, the White House in Washington, or the Reichstag in Berlin, these centres of political power are symbolized by the very buildings themselves. And, like so much of history, this is nothing new.

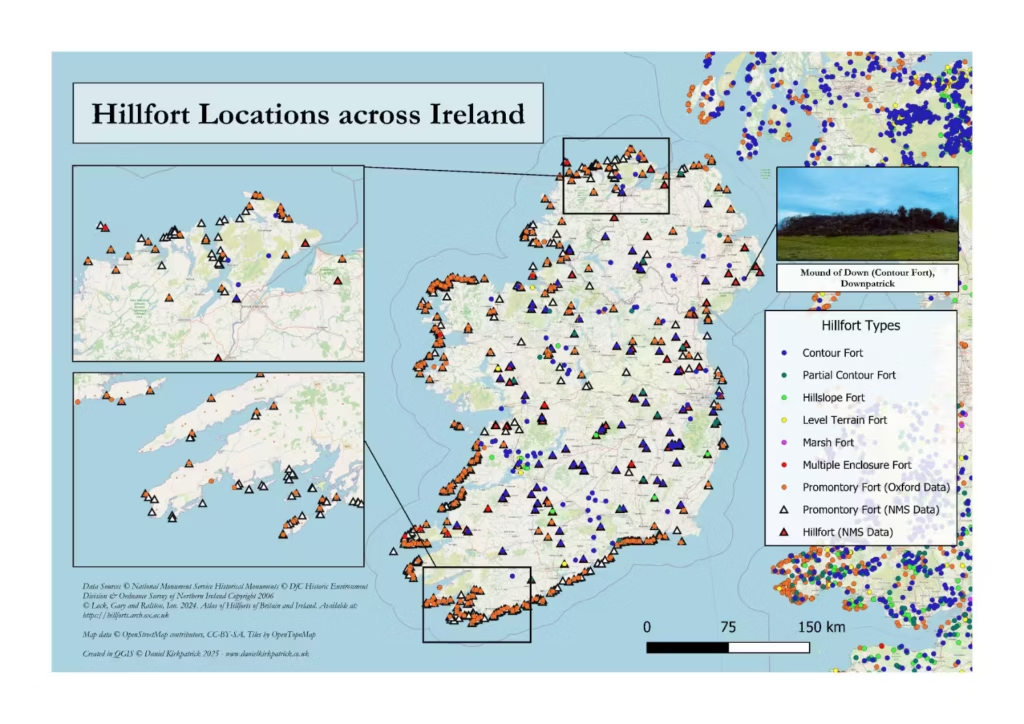

If you drive around Ireland today, it’ll not be long before you pass the ruins of an ancient hillfort. Located on strategic positions high above the landscape, many are obvious local landmarks. In fact, according to a recent study, over 500 hillforts have been documented across the whole island.1 For those counting, that’s more than 15 per county. But unless you’re one of the handful of scholars who study these ubiquitous ancient landmarks, you probably don’t know much about them. My recent post on Irish hillforts is like the painting of what life looked like in these settlements, whereas this post looks at the brush-strokes and contours of the paint – the detail.

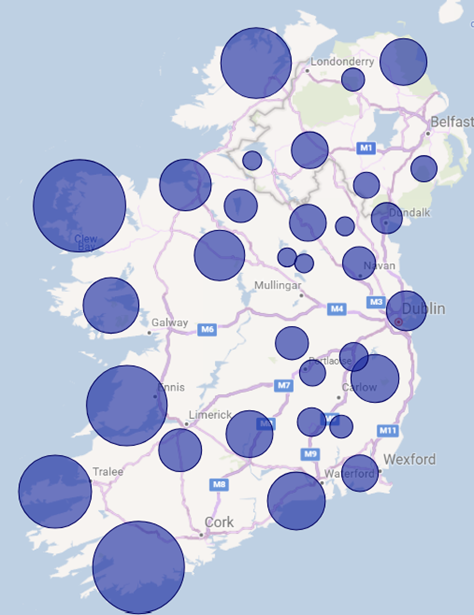

This post begins with an interactive map showing all hillforts which have been mapped by the respective governments of Ireland and Northern Ireland. It then sets these sites in the context of regional trends and some of the most recent research.

Interactive Map of Irish hillforts

This interactive map was created in QGIS using data from both Government datasets alongside a really impressive dataset from the Oxford University Atlas of Hillforts. Copyright for the data and basemaps attribution is as follows:

Data Sources

© National Monument Service Historical Monuments

© DfC Historic Environment Division & Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland Copyright 2006

© Lock, Gary and Ralston, Ian. 2024. Atlas of Hillforts of Britain and Ireland. Available at: https://hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk

Map data

© OpenStreetMap contributors, CC-BY-SA, Tiles by OpenStreetMap

Defining the Irish Hillfort?

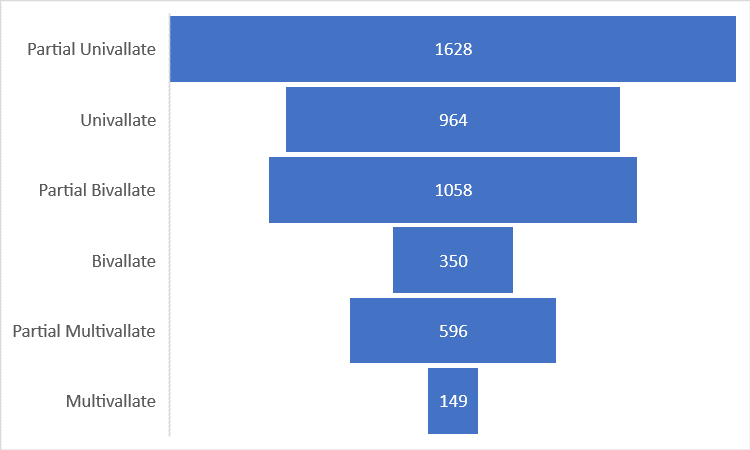

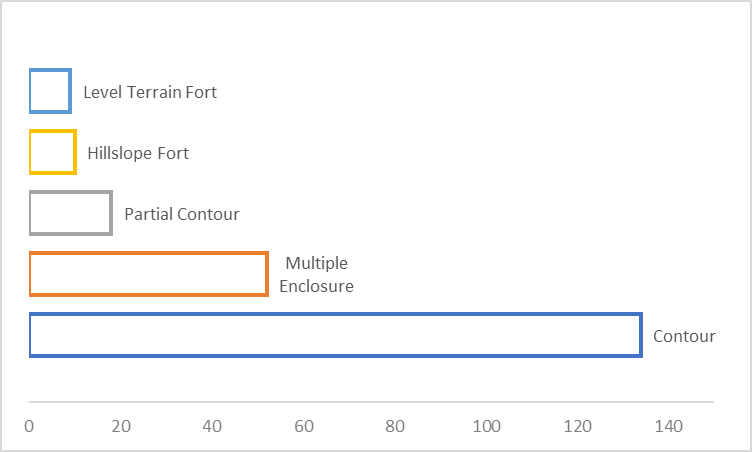

Hillforts were built all across Europe from the late prehistoric period onwards. Ranging considerably in size, hillforts typically consisted of a palisade wall with one or more external ramparts. Most British and Irish hillforts were univallate (had only a single circuit of defensive earthworks), but there were many with further earthworks as shown in Figure 1.2

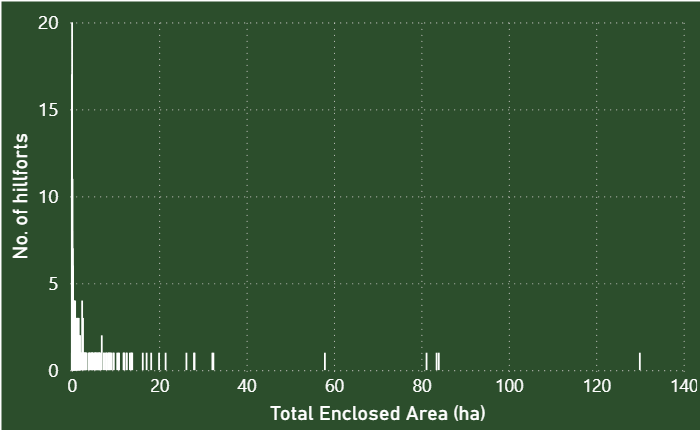

Inside this defensive exterior would have been a settlement with a mix of homesteads and industrial buildings depending on the location, dates, and size. The average hillfort size across both Britain and Ireland was 18,200m2, roughly equivalent to 72 medium sized house plots. Whereas in Ireland it was even larger at 27,800m2, a whooping 111 medium sized house plots. However, when you look more closely at the data, hillfort sizes are heavily skewed as 64% were less than 10,000m2. This suggests that the vast majority of Irish hillforts were relatively small, supporting less than 40 buildings. And then there were a few huge forts.3 With this sense of space, it makes sense to turn to its usage – to the life of these hillfort dwellers.

Data Visualisations on Irish Hillfort Locations, Density, Size and Classifications

A day in the life of a hillfort

What life looked like inside these ancient fortifications is still widely debated. Generalisation are difficult and often misleading.4 But we can make several confident assumptions. To begin with, these forts were used as settlements, so life would have demanded all of the daily necessities of the time. They’d have access to trade and places for hospitality to host guests and travellers. There would have been craftsmen of at least basic items (carpenters, bone-workers, weavers, smiths and so on). There would be access to freshwater and typically space for pasture.

Given their fortified nature, valuable goods and foodstuffs would have likely been stored inside, particularly cattle – a point we’ll return to later. Moreover, they’d have had a barracks and some martial buildings to support the defences depending on the fort size. But, as I note in my earlier post, these were not martial settlements in the Roman sense, housing large standing forces of militia.

Hillforts as Palaces of Power

There would have been a Chief with all the trappings of power including their residence, a place for hosting, servant quarters. Indeed, many of these elements are described in the Irish myths of the Ulster Cycle giving us a vivid depiction of what life was like. For instance, the description of Rathcroghan, the famed hillfort and palace of Queen Maeve, portrays a lavish royal residence which would be the envy of many today. The intricate carvings, bronze and silver facings, ornate oak ceilings and floors, combined to overwhelm visitors with the power of its inhabitants.

Similar, and even grander, examples can be found at the other Royal sites of Tara, Emain Macha and Dun Ailinne. But these are the exception rather than the rule. The vast majority of hillforts were nowhere near the size or scale of these palaces. So while a chief’s residence would have undoubtedly been a central part of any hillfort, they were much more modest and functional than these lavish centres of power.

Table of Significant Hillforts in Ireland

| Name | County | Period | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hill of Tara | Meath | c. 1000 BC | Ceremonial royal site, seat of High Kings, multiple ringforts |

| Navan Fort | Armagh | c. 95 BC | Associated with Emain Macha, large ceremonial wooden structure |

| Dún Ailinne | Kildare | c. 400 BC–AD 400 | Ritual centre, royal inauguration site for Leinster kings |

| Knockaulin | Kildare | Iron Age | Massive hilltop enclosure with prehistoric activity |

| Rathcroghan | Roscommon | c. 300 BC–AD 400 | Connacht royal complex, Oweynagat (“Cave of the Cats”) nearby |

| Cahercommaun | Clare | c. 400–100 BC | Triple-stone fort on a cliff edge, spectacular defensive setting |

| Mooghaun Hillfort | Clare | c. 1000 BC | Largest known hillfort in Ireland, associated with gold hoard |

| Knockdrum Fort | Cork | Late Bronze/Iron Age | Stone hillfort with internal buildings and outer ditch |

Hillfort Designs

Given their name, it may seem ridiculous to ask where hillforts were located (on a hill?). But the type and location of these settlements tells us a lot about their purpose and design. To start with, the vast majority of Irish hillforts (60%) were promontory forts. These used the natural landscape to provide defensive barriers, usually in the form of 2 or 3 steep sides such as on a rocky ridge. These were both inland and on the coast. By having natural defensive features, the forts could expend less resources by concentrating on the only vulnerable points. The costs in materials and labour made these forts were prohibitively high for but the most powerful. Any option to keep costs down would have been considered. So by using the natural defensive features of the landscape, builders could focus resources on a smaller area, reducing cost while not sacrificing their defensive strength.

Promontory forts being the most prevalent type, of the remaining forts around 28% were contour forts. With artificial ramparts on all sides (or natural steep slopes), these were situated on natural hilltop positions and are likely what you imagine of when someone mentions ‘hillfort’. Dotted around the countryside, the remains of these forts are as almost ubiquitous as the hills themselves. They appear to rise up like spears in the ground, puncturing the landscape with their imposing presence. One interesting finding about these, is how they were often located within sight of other similar forts. The prevailing theory is that if one were attacked, this enabled it to give warning to those nearby, thereby acting as a form of ancient collective defensive against raiders.

So now we have an idea of what the forts looked like, how they were built, and the size and scale. This brings us to where exactly in Ireland they were located.

Hillfort Locations

The Sea View

With promontory forts being the most common type, it is not particularly surprising that we see the greatest concentration of hillforts along the Irish coastline. There are likely many reasons and no concluding explanations, but for me I think there are a few key reasons why coastal positions were the most popular.

First is their strategic importance. The Irish coast has always been a critical navigation route for trade and travel. Sea transport was often safer (both from wild animals and bandits) and possibly faster (due to the weather and the quality of tracks). Building a fort on the coast also had the advantage of being easier to defend with natural, unassailable cliffs. Typically, they were also built along strategic waterways or travel routes, thereby enabling the chief to tax and control trade in the wider region.

Trade Hubs and Sites of Industry

Next is their economic importance. Huge volumes of lumber would have been required for such forts, and the sea provided a natural trade-route to transport such materials. The ready supply of fish and sea materials (such as kelp and salt) would have been a much more reliable source of food and income, being less dependent on weather conditions than the agrarian alternatives. This brings us to the third reason.

Lastly, and probably most important, is that these forts were located in areas favouring pasture over agriculture. The ancient Irish had an obsession of with cattle. It was how wealth was measure, power was evaluated, restitution compensated, and life itself protected. For, in your herd you had a source of a vast array of critical commodities, from meat to bone, fat to leather. While evidence of milking in early Ireland wasn’t particularly common, the plethora of other materials makes a compelling argument for their value. In this way, it makes sense that hillforts, which provided a key way to guard and protect your cattle, were located in regions favouring pasture over agriculture.

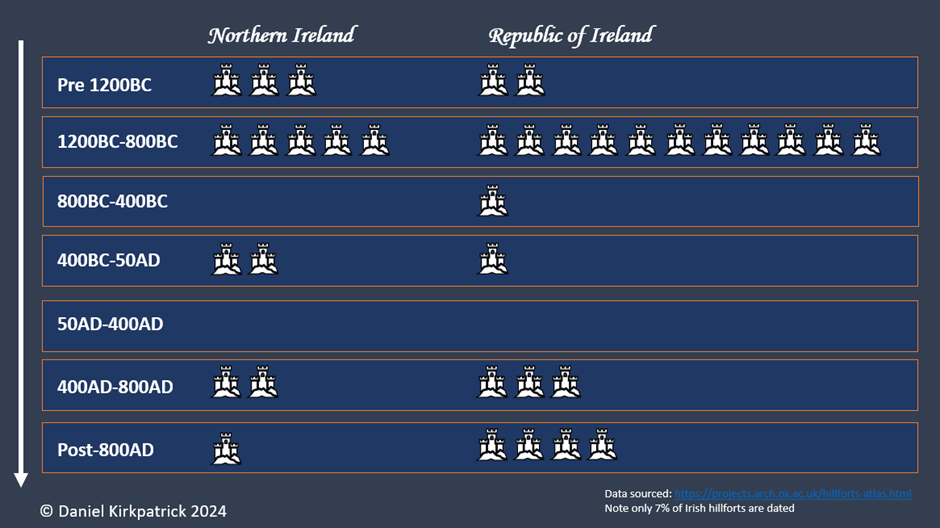

When were they built?

Dating of hillforts is fraught with incomplete data and skewed results. But there are a few observations we can make. The first is that there appears to have been a proportionate increase in hillfort building during the late bronze age and again in the late Iron Age. With the agricultural innovations in the late Iron Age and corresponding population increase, it is unsurprising that the number of hillforts increased too. Like our modern-day urbanisation, this ancient programme of fort building would have reflected the increased wealth generated by the growing population.

So while the Iron Age expansion of hillforts is quite easily explained away, the late Bronze Age is more difficult. One option would be to turn to the ancient myths which describe this period, the Ulster Cycle. While fraught with bias, they do provide several compelling theories. First is the frequent reference to raids and internecine conflicts which appear to have taken place. When considered against the wider decline in importance of bronze and advent of iron, this may have some truth.

As bronze declined in importance, the centres of power would have likewise shifted resulting in a highly unstable political environment. Shifting alliances and wealth would have, as we know throughout history, increase in fighting and war. Hillforts would have provided important centres for power, consolidating newly acquired land. Likewise, the advent of iron resulted in easier access to more lethal weapons and armour. Reinforced shields and weapons of greater strength would have only increased the risk of conflict. Hillforts therefore represent the shifting power struggles which would have ruptured the Irish political system during these centuries.

Significance of Hillforts Today

Irish hillforts are clearly important markers of ancient Ireland. Their enduring presence is emblematic of their historical importance. For me as a writer, they are reflection of the political and social structures of Ireland’s Iron Age. They were centres of life, much like our contemporary towns and cities. And yet, like so much of history, they are in danger of fading away.

Recent analysis of hillforts reveals that around 25% of known Irish hillfort sites have been destroyed. But this is almost certainly much lower than the real figure. To state the obvious – we don’t know what we don’t know. So to find destroyed hillfort sites is like searching for sandcastles after the tide. But it’s never too late for those that remain.

As a layman of such things, I won’t venture any more of an opinion except to reinforce the point of their historical significance. For they represent markers of Ireland’s identity. To lose them would be to lose something of what makes this island unique. It literally ground’s Irish identity, displacing the polarising narratives which seem to dominate so much of life today. So let’s celebrate and protect their presence, remembering it is sites such as these which preserve the memory of what came before.

Frequently Asked Questions: Irish Hillforts

Irish hillforts were large fortified settlements (often on hilltops or promontories) built in ancient Ireland (primarily Bronze/Iron Age). They typically enclosed homesteads, craft workshops and cattle pens, and served as centers of power. In these communities a local chief lived with family and retainers, hosting guests and controlling regional trade. (Many were more like villages than simple forts.)

They provide tangible links to ancient Ireland’s society and politics. As enduring landmarks, hillforts help us understand Iron Age communities and Irish identity. Protecting them preserves Ireland’s unique heritage, since they are among the few physical markers of our distant past

Many hillforts survive as earthwork ruins or archaeological sites. Famous examples like the Hill of Tara or Navan Fort (Emain Macha) are still studied and can be visited. However, about 25% of known hillfort sites have been destroyed by modern development, so preservation varies. The remaining sites are treasured heritage sites.

Over 500 hillforts have been identified across Ireland. They often occupy strategic hills, ridges or coastal promontories. About 60% are coastal promontory forts (using cliffs as natural defenses). Others sit on inland summits (contour forts) or river bends. This location strategy leveraged terrain for defense and access to resources.

Daily life in a hillfort included farming, crafting and trade. Inside the walls were homes, storage for food and goods, workshops (weaving, metalworking, etc.), and animals like cattle. Chiefs had residences and guest quarters. While defended by earthworks or palisades, hillforts were vibrant communities – not just military garrisons.

Most were constructed during the late Bronze Age and especially the Iron Age, coinciding with population growth and technological change. Innovations in farming and tools made larger communities possible, and periods of social conflict (e.g. declining Bronze wealth) spurred the building of defenses. In short, hillforts rose during times of wealth and warfare as fortified settlements for emerging elites.

Please note all graphs depicted in this post were produced by me so are under the following license: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

- For more background on this research see here: https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:091b8d2a-e222-4c17-82f9-3a0718ee9485/files/r9593tw03t ↩︎

- These statistics and all cited throughout this post are based on my analysis of the Hillfort Atlas ↩︎

- See for instance Spinans Hill 2 which was 131ha in size https://hillforts.arch.ox.ac.uk/records/IR0727.html ↩︎

- For a good summary of life in Welsh hillforts see here: https://the-past.com/feature/power-of-place-illuminating-iron-age-hillforts-in-wales/ ↩︎

For wider reading on the subject see:

O’Driscoll, J., 2017. Hillforts in prehistoric Ireland: a costly display of power?. World Archaeology, 49(4), pp.506-525.

Vengalis, R., 2016. Old and middle iron Age settlements and hillforts. A Hundred Years of Archaeological Discoveries in Lithuania. Vilnius: Society of the Lithuanian Archaeology, pp.160-181.

Armit, I., 2007, January. Hillforts at War: From Maiden Castle to Taniwaha Pā. In Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society (Vol. 73, pp. 25-37). Cambridge University Press.