In Ireland, festivals are more than just seasonal markers or religious observances. They are signposts pointing back through history to a time of pre-Christian rites, agricultural rhythms, and deep mythological symbolism. The Irish language, with its rich descriptive texture and historical layering, encodes a worldview where time, nature, and the sacred are intertwined. Names like Samhain, Imbolc, and Lughnasadh, are not arbitrary labels but fossilised fragments of cultural memory. They tell us when communities gathered, what they feared or revered, and which deities once governed the land and sky. Understanding the etymology of Irish festivals reveals a vivid picture of ancient Ireland – one which this post stops to consider.

Through unpacking this festival etymology — from fire rites to Christian feast days — we can understand how language preserves ancient cultural traditions. By comparing these names with similar observances in other ancient cultures such as the Gauls, Anglo-Saxons, and Greeks, we can trace a pan-European consciousness of the seasons, but also pinpoint what made the Irish experience unique. So let’s turn to these four great festivals of the ancient Irish calendar.

Meaning and Significance of the Four Great Gaelic Festivals

The oldest named festivals in Irish tradition form what scholars often call the Gaelic ritual calendar — four major quarter days that correspond to critical points in the agricultural and cosmic year. These are Samhain, Imbolc, Beltaine, and Lughnasadh — all names originating in Old Irish, and all revealing insights into the seasonal psyche of early Ireland.

Table: The Linguistic Layers of the Quarter Festivals

| Festival | Literal Meaning | Associated Deity/Myth | Primary Function | Parallel Traditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Samhain | “Summer’s end” | Spirits / Ancestors | Threshold, death, liminality | Anglo-Saxon Blōtmōnaþ |

| Imbolc | “In the belly” | Brigid | Fertility, spring return | Roman Februa |

| Bealtaine | “Bel’s fire” | Bel (possible deity) | Fire ritual, protection | Gaulish Belenus, Vedic Agni |

| Lughnasadh | “Assembly of Lugh” | Lugh | Harvest, games, tribute | Roman Consualia |

Samhain – Summer’s End and the Opening of the Otherworld

The festival of Samhain, traditionally observed around 1 November, is linguistically rooted in the Old Irish sam (summer) and fuin (end), making its literal translation “summer’s end.” This name reflects a fundamental cosmological belief in ancient Ireland: that the year was divided into a bright and a dark half, with Samhain marking the end of the light and the beginning of the winter season.

More than a calendar event, Samhain was a moment of transition and liminality — when the boundary between the living and the dead was believed to thin. The dead might return, and the aos sí (otherworldly beings) could cross into the human realm. This thematic emphasis on death and transition echoes similar festivals in other cultures.

Similarly, the Anglo-Saxons observed Blōtmōnaþ, or “sacrifice-month,” in November, while the Romans held Lemuria (though earlier in the year), during which rites were performed to appease the restless dead. What distinguishes Samhain, however, is the specificity of its name — it directly refers to the temporal shift and changing season.

Imbolc – The Language of Fertility and Light

Imbolc, celebrated on 1 February, is derived from the Old Irish phrase i mbolg, meaning “in the belly.” The name is an unmistakable reference to the early stages of lambing season, when ewes begin to carry young. This etymology reveals a uniquely grounded focus in early Irish culture on biological and agricultural rhythms as indicators of seasonal change.

Imbolc was closely associated with Brigid, the pre-Christian goddess of fertility, healing, and poetry — later syncretised as Saint Brigid in Christian tradition. The festival heralded the return of light and new life, yet unlike solstices or equinoxes, its name is not astronomical but embodied: it is about gestation, about life developing unseen but inevitable.

This biological grounding finds parallels in Roman Februa, a purification festival, and the Greek Anthesteria, both of which marked seasonal transition and renewal. But Imbolc stands out in how explicitly its name connects with the natural processes of birth and reproduction — its language encodes hope and quiet transformation.

Bealtaine – Fire as Protection and Passage

Bealtaine – taking place around 1 May – is named for its defining ritual, namely the lighting of protective fires. The word is likely a compound of Bel — possibly a deity related to brightness or light, perhaps linked etymologically to the Gaulish god Belenus — and tene, meaning “fire.” Thus, Bealtaine literally means “Bel’s fire.”

This was a liminal moment in the calendar, not unlike Samhain, though facing the opposite direction — into the growing season. Cattle were driven between two fires to purify and protect them before being sent to summer pastures, and the community itself was ritually safeguarded against disease and malevolent forces. The rite echoes broader Indo-European traditions of fire worship, particularly the Vedic Agni cult in India and the solar associations of continental Celtic religion.

While many cultures used fire in seasonal rites, the Irish naming of the festival after the fire itself — rather than the time or the deity alone — reflects an emphasis on ritual action as the centre of meaning.

“Lughnasadh – The God in the Grain

Lughnasadh – celebrated around 1 August – offers the most explicitly mythological name of the four Gaelic festivals. The word combines Lugh, the god of light, skill, and kingship, with násad, meaning assembly or gathering. The result — “the assembly of Lugh” — preserves both the deity and the function of the celebration.

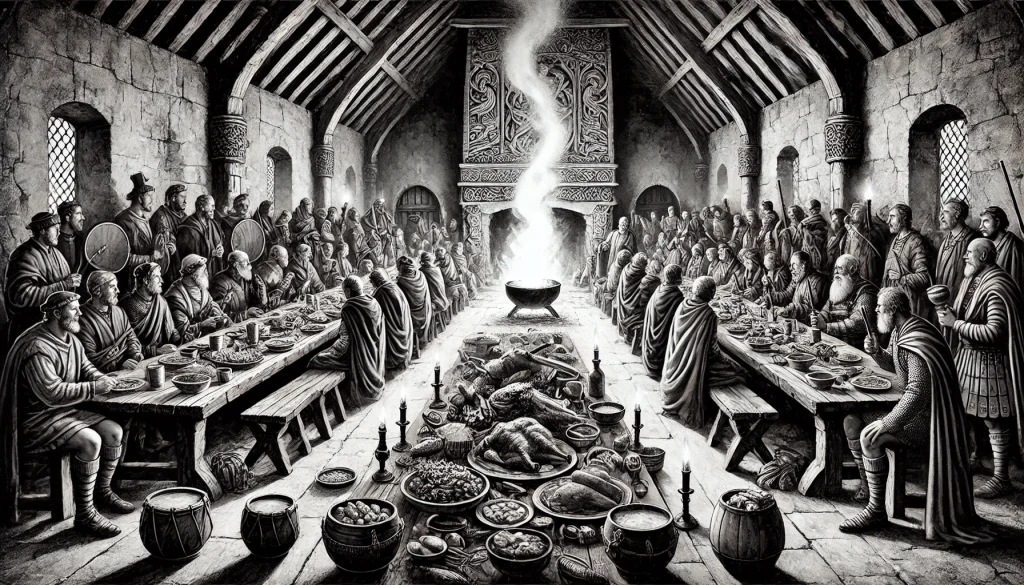

According to medieval Irish sources, the festival was established by Lugh to honour his foster-mother Tailtiu, who died clearing the land for agriculture. This story not only places divine sacrifice at the heart of harvest, but it grounds the practice in specific landscape and kinship lore. Lughnasadh was marked by fairs, athletic contests, trial marriages, and offerings of the first fruits. Effectively a communal expression of gratitude and renewal.

Roman Consualia, dedicated to the god Consus, similarly tied harvest to divine favour and horse racing. But it lacked the personified mythical narrative embedded in Lughnasadh’s etymology.

The Irish festival name thus reveals a culture where myth, deity, and seasonal economy were deeply entwined — and remembered not just in action, but in speech.

Christian Feast Days and Solstices: Layers of Meaning

While the four major festivals—Samhain, Imbolc, Bealtaine, and Lughnasadh—anchor the traditional Gaelic calendar, later centuries introduced new names and observances, especially with the arrival of Christianity. These new feast days did not erase earlier traditions but rather layered new meanings onto them.

By examining the names of these events, we can trace both cultural continuity and strategic transformation in Ireland’s ritual landscape.

Saint Days

Take Lá Fhéile Bríde, the Irish name for Saint Brigid’s Day. Linguistically, Lá Fhéile means “feast day,” while Bríde (genitive of Bríd) directly invokes the saint herself—who is, of course, a Christianised continuation of the earlier goddess Brigid. Thus, even in Christian usage, the name retains echoes of the divine feminine, seasonal fertility, and poetic inspiration.

Similarly, Lá ’le Pádraig (St Patrick’s Day) translates as “the day of Patrick’s festival.” While modern interpretations frame it around national identity, the name follows the same formulaic structure as older feast days, preserving both religious and social significance in its phrasing.

Solstices

The summer solstice, though not one of the four major named festivals in Irish tradition, is deeply embedded in the archaeological record. Sites such as Newgrange and Loughcrew demonstrate sophisticated solar alignment, particularly with the winter solstice. Yet there is no Old Irish name for the summer solstice preserved in medieval texts.

This silence in the language may reflect a ritual tradition more focused on local monuments and ancestral gatherings than calendrical regularity. Later, feast days like St John’s Eve (Lá Fhéile Eoin) came to be celebrated near midsummer. The name retains the Christian form, but the customs—such as lighting bonfires—resemble Bealtaine more than scripture. Once again, the name conceals and preserves: the “feast of John” acts as a linguistic vessel for a much older celebration of light and fire.

Irish Christmas

Even Christmas (Nollaig) bears etymological interest. The Irish word Nollaig comes from the Latin natalicia, meaning “birth,” reflecting the Christian story. But in practice, Irish Christmas traditions often integrated pre-Christian customs, from midwinter feasting to the veneration of evergreens and symbols of renewal. Unlike English, where the name “Christmas” foregrounds Christ, the Irish word hides the religious reference in a Latinised root, suggesting a smoother linguistic fusion with earlier seasonal practices.

Table: Comparison between Irish Christian Festivals and those of Saxons, Gauls & Greeks

| Irish Feast Day | Irish Name | Timing | Similar in Anglo-Saxon | Gaulish/Roman Equivalent | Greek Parallel | Notes on Linguistic/Cultural Overlap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St Brigid’s Day | Lá Fhéile Bríde | 1 February | Imbolc > Candlemas | Festival of Juno Februa (2 Feb) | Anthesteria (Feb/March, fertility) | “Fhéile” = feast; Bríde links to Brigid, a pagan goddess. |

| St Patrick’s Day | Lá ’le Pádraig | 17 March | Vernal rites emerging | Liberalia (17 March, fertility) | Dionysia (early spring revelry) | Pádraig = Patrick, but timing and celebration echo seasonal rebirth. |

| Easter | Cáisc (from Lat. Pascha) | March–April (varies) | Ēostre (spring goddess) | Resurrection rituals (Roman) | Eleusinian Mysteries (spring renewal) | Irish Cáisc reflects Latin root, but customs reflect seasonal rebirth. |

| St John’s Eve | Lá Fhéile Eoin | 23–24 June (Midsummer) | Midsummer fires | Sol Invictus / Feast of St John | Kronia (June/July harvest rites) | Bonfire tradition continues pagan solar observance. |

| All Saints’ Day | Lá na Naomh Uile | 1 November | Samhain > All Hallows | Lemuria (Roman ancestor rites) | Genesia (Greek ancestral festival) | “Naomh” = saint; date echoes Samhain’s ancestral focus. |

| Christmas | Nollaig | 25 December | Midwinter / Yule | Dies Natalis Solis Invicti | Lenaia (winter Dionysian festival) | Nollaig from natalicia, Latin for “birth,” overlays solar worship. |

| Epiphany | Lá Fhéile Eipifine | 6 January | Twelfth Night traditions | Roman calendar reset (Kalends) | Theogony-themed sacred time | Language mirrors Christian theology, but time marks renewal. |

These examples reveal a subtle but powerful finding: names are not passive labels. They encode cultural inheritance. In Ireland, the shift from pagan to Christian timekeeping did not replace the language of ritual—it repurposed it. Feast days still announce sacred time, and solstice rituals are still whispered through the alignment of stones and the lighting of fire. The Irish calendar, when read through the lens of language, is not a straight road but a palimpsest: one belief system written over another, never fully erased.

Local Calendars and Forgotten Festivals

While national observances such as Samhain or Lá Fhéile Pádraig dominate the Irish cultural landscape today, Ireland’s past is rich with regional festivals and sacred days that never made it into widespread ecclesiastical calendars. These were often tied to particular locations, family traditions, or seasonal markers, and their memory survives chiefly through place-names, oral tradition, and occasionally archaeological features.

Day of the Wren

One of the clearest examples of local Irish festivals is Lá an Dreoilín (“Day of the Wren”), observed on 26 December. Though now associated with St Stephen’s Day, this custom of hunting or parading with a wren — an dreoilín in Irish — has ancient echoes.

The bird itself may symbolise sacrifice or the old year, with parallels found in Celtic and Classical ritual where small animals were symbolic offerings. The use of Irish in the name (Lá an Dreoilín) ensures that the wren, and not the saint, remains the day’s primary symbol in linguistic memory.

Garland Sunday

Another example is Garland Sunday, often celebrated on the last Sunday of July. In Irish, this was sometimes known as Domhnach Crom Dubh (“Crom Dubh’s Sunday”), named after a mysterious, likely pre-Christian figure.

Local fairs, hilltop gatherings, and rituals were held on this day, especially in counties Kerry, Mayo and Sligo.

Crom Dubh’s name, meaning “Dark Bent One,” may represent a harvest spirit or local deity supplanted by later Christian legends. While the religious overtone has faded, the linguistic retention of his name in place-names and oral calendars preserves a trace of the divine in the local landscape.

Reek Sunday

Reek Sunday, the last Sunday in July, when thousands climb Croagh Patrick, is another regional observance with deep linguistic and ritual layers. While today it’s a Christian pilgrimage site honouring St Patrick, the mountain’s older name—Cruachán Aigle—and its prominence in Dindshenchas lore suggest it was a sacred site long before its saintly associations.

The word cruachán (“conical hill”) not only describes the shape but implies ritual status, as similar terms appear in place-names linked to other high places of worship.

Interpreting the Legacy of Irish Festivals

The language of Irish festivals is more than poetic flourish—it is a cultural archive. Each name is a preserves echoes of pre-Christian rituals, mythological figures, and agrarian or cosmological cycles. In the names of events – like Lá Fhéile Bríde, Bealtaine, or Lughnasa -we find layered histories that reach back to the Bronze Age and beyond, surviving the overlay of Christian reinterpretation and colonial suppression.

By tracing the etymology of these festivals, it becomes evident that the Irish calendar is not simply a list of events but a narrative structure—a story of people’s relationships with their gods, the land, the seasons, and one another. Language acts here as a mnemonic: a way to remember sacred time and transmit cultural memory. Names such as Imbolc (from i mbolg, “in the belly”) reflect agricultural lifecycles; Lughnasa commemorates a divine hero; Bealtaine encodes ancient fire rites. Even Christian feast names like Lá Fhéile Pádraig or Lá Fhéile Eoin retain linguistic forms shaped by earlier, indigenous modes of marking time.

Therefore by understanding the etymology of Irish festivals, we can peer into the ancient history of Ireland itself. Its calendar becomes a form of cultural cartography, mapping belief through vocabulary. And in this map, words are not just signposts—they are ancient places themselves.

Frequently Asked Questions: Etymology of Irish Festivals

Imbolc comes from the Old Irish i mbolg, meaning “in the belly,” referring to lambing season and fertility. It marks the beginning of spring and is linked to the goddess Brigid.

Feast days like Lá Fhéile Bríde (Brigid’s Day) kept Irish language forms, preserving continuity with earlier pagan rites and reinforcing national identity through religious observance.

No. Samhain means “summer’s end” and predates Halloween. It marked a liminal time when the boundaries between worlds were thin, allowing spirits to pass through.

Lughnasa is named for the god Lugh and marked a tribal assembly and harvest festival. The name itself encodes its religious and social significance.

The word Bealtaine combines Bel (possibly a deity associated with brightness) and tene (fire), referencing large bonfires lit for purification and transition into summer.