For anyone tracing Irish ancestry, family history often reaches back a few hundred years — to famine, migration, or clan origins. Yet the story of Ireland stretches far deeper. At Mountsandel Fort in Coleraine, we find traces of life from around 8000 BC — a staggering 400 generations before written history. This quiet riverside site, overlooking the Bann, marks the earliest known human settlement in Ireland. Here, small bands of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers built circular huts, fished the river, and shaped the first chapter of Ireland’s human story.

This post explores the archaeological evidence discovered at the site, what it tells us about how life would have been like, and the sites subsequent transformation throughout the millennia which followed.

The Settlement of the Mountsandel Fort

If you were to visit Mountsandel today you could be forgiven for wondering what the fuss is all about. Situated on the edge of the River Bann, the settlement looms 30m above the waters on the edge of a beautiful woodland. But a closer look will show just how strategic a location it would have been to our ancestors.

Overland travel in ancient Ireland was dangerous and challenging due to dense woodlands and an abundance of predators. Rivers and coasts offered the safest and fastest way to traverse the island. Evidence of water transport has been well-established dating back almost as long as humans themselves. Even after humans had developed an agrarian society, the abundance of salmon and eels would have been invaluable. Situated on an easily defensive escarpment and overlooking a key fording point in the river, makes this a clear choice for any early human settlement.

In fact, evidence of human activity dates not only back to the ancient Mesolithic, but also throughout Irish history with many other later buildings and artifacts discovered. But if you were to visit this site today, it is hard to imagine what secrets lie buried beneath the verdant, grassy hilltop. For that we must turn to my favourite subject, to archaeology.

Archaeological Significance

Finding evidence of the earliest human activity in Ireland has occupied archaeologists for almost as long as the discipline has existed. But the Mesolithic site of Mountsandel presents one of the earliest yet most complete discoveries in this search. From it we can develop a picture of the diet, lifestyle, and living conditions these ancient ancestors enjoyed. It gives us a picture of what life involved and what our forebears might have been like. Similar to when our family histories reveal some exciting secret, these finds provide us with rare insights into these ancient Irish peoples.

In the 1970s, archaeologist Peter Woodman conducted a series of excavations which revealed surprising evidence of human habitation. It was surprising because it dated the site to a staggering 8000BC – the time of hunter-gatherers.1

Archaeological Evidence

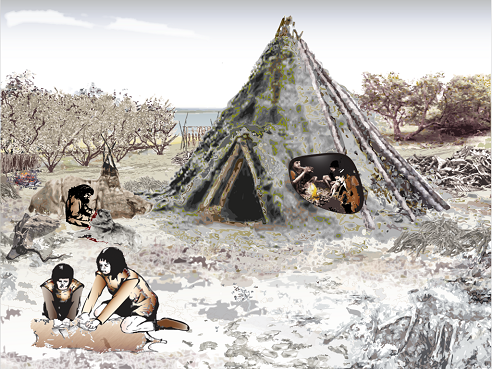

The settlement consisted of a series of wigwam-shaped huts, like sliced eggs, grouped together. Each ranged in size between 3-6m in diameter. Archaeologists estimate this could have supported anywhere between 3 and 15 people.2 The huts themselves were built using a structure of sapling poles overlaid with hide and turf. Inside, a small firepit sat at the centre.

Within these pits were found the remains of fish (mostly salmon and eel), birds, wild pig, hare, and even a dog bone. You can imagine these early hunters using traps and spears to catch the migrating salmon or trapping eels. Able foragers, there was evidence of hazelnuts, water-lily and apple seeds, providing a relatively varied and full diet for this period of history. These were a healthy and likely happy people.

They were also able builders and craftsmen. Besides the structures themselves (which only show us a partial impression of what they built), over 1100 flint tools were discovered at the site. Varying in shape and size, these picks, axes, and hammers, show just how developed and skilled these craftsmen were. But the sheer number and range begs a wider question of where they originated from.

Ancient culture and society

Significant research has gone into the provenance of such artifacts with much speculation. At the very least, it is likely there was a small industry around harvesting and producing these tools. Nearby quarries would have been used from the surrounding coastline. It is very possible that other settlements and trade existed to facilitate the production and transportation of these.

There was also evidence of red ochre discovered on one of the axe-heads.3 This may indicate the use of paint for ceremonial purposes, but such speculation is just that – speculation. All we can say for certain is that they were using the paint. You can let your imagination fill in the blanks. But to even have had access to paint shows these people had some form of culture and practices to require it. Life wasn’t merely about survival. Indeed, life would have reflected much of what we know and can relate to today.

A Day in Ancient Ireland

You can picture the scene. Waking up in your smoke-filled hut to the smells of burnt fat and soot from the night before. After wrapping up in your fur and hide garments, you begin your daily routine. Rising with the dawn, you start by checking your traps down by the river, taking stock of any needing mending. You pause to listen to the sound of gulls and gushing rapids.

As the day wears on, everyone knows their duties. Children will be gathering firewood. Others mending traps and tools. Foragers will range into the forests or preserving the stocks already harvested. Clothes will be mended using bone tools and animal sinews. Like a healthy body, the settlement operates together for the survival of the whole.

But not only this, they would have there own special days: celebrations when they gathered an abundant harvest, inexplicable weather they’d regard with reverent wonder, or celestial events they observe with each cycle. Children would have games. Elders would have stories. Parents rules. Craftsmen specialisms. Cooks recipes. They would laugh and cry, sing and dance. In many ways, we can see much more in common with these people, than the 10,000 years which separate us.

Mountsandel Fort Post-Mesolithic Use

Mount Sandel remained occupied after the Mesolithic era, with evidence hinting at Bronze- and Iron-Age activity in the wider River Bann valley. Artefacts dredged from the Bann during channel works include Neolithic and Bronze-Age finds, suggesting persistent albeit lighter occupation or use of the area between c. 4,000–500 BC.

The prominent earthwork mound known today as Mount Sandel Fort is a much later construction—dating from the Anglo-Norman period, likely the late 12th century. Positioned strategically on a natural promontory above the Bann, it features a large oval mound encircled by a deep ditch. Archaeologists interpret this mound as an unfinished—or possibly abandoned—motte-and-bailey castle, a type of Norman fortification common throughout Ireland following the Norman invasion (c. 1170–1230 AD).

Archaeological monitoring during bank-stabilisation work in 2014 revealed a few unstratified flint tools of Mesolithic date but also 13th-century coarseware pottery shards on the mound itself, which further strengthen its attribution to Norman activity. No structural remains—such as stone walls or timber palisades—have been uncovered within the mound, so the precise nature and extent of medieval occupation remain uncertain and unexcavated.

Following its medieval use, the site eventually fell into disrepair. In the 21st century, it has been placed under State Care for heritage conservation. Stabilisation efforts—such as re-forming the ditch slopes with stone core and reseeding—were undertaken in 2014 to prevent erosion and maintain the integrity of the monument .

Table of Mountsandel Fort’s Historical Timeline

| Period | Event / Development |

|---|---|

| c. 7600–7900 BC (Mesolithic) | Earliest human activity in the area evidenced by flint tools and campsite remains in nearby woodlands. This precedes the fort itself. |

| Neolithic–Bronze Age | Artefacts found in the River Bann suggest occasional use, but no permanent structure from this era at the fort site. |

| Late 12th century (c. 1197) | Construction of the earthwork mound and surrounding ditch, interpreted as a Norman motte-and-bailey castle (possibly unfinished or abandoned). |

| Medieval period (13th century) | Unstratified sherds of coarse medieval pottery found on the mound confirm Norman-era activity; structure itself avoided full excavation. |

| Possibly 16th century onwards | The mound may have been modified for artillery or adapted for later defensive use, though exact evidence is limited. |

| 2014 (21 May – 6 June) | A bank-slip triggered erosion; the fort received conservation work including stabilisation, re-profiling, and reseeding of the mound and ditch. |

| Present Day | The site is a publicly accessible State Care Historic Monument with interpretive signage, woodland trails, and free entry year-round. |

The Mountsandel Fort’s Significance Today

For me it is bittersweet researching this site, for I grew up within mere miles of its location, yet never knowing its significance. This is the reality for so many of us in Ireland; where the history and present rarely meet. And when they do meet, it is rarely a happy reunion. But I hope seeing just how incredible these discoveries are, perhaps you may see the beauty and richness of this small island. That it represents much more than what our tireless endeavours into genealogy show; a collective narrative which shows how much more we have in common than separates us.

And that is what Mountsandel represents for me. It’s a wonderful portrait of life in ancient Ireland, of what our descendants 400-generations ago lived. We are all so quick to point to difference that we forget how much we share with those around us. If even with the passing of 10,000 years we can find so much in common, how much more can we with our neighbours and communities today?

Visiting Mount Sandel Fort

Mount Sandel Fort is easily reached via Mountsandel Road just outside Coleraine, with its own small car park for visitors. Entry is free and open-access year-round, and the Causeway Coastal Route is signposted to the site. Once there, a well-maintained trail leads through Mountsandel Wood up to the fort. The surrounding woodland is gentle to walk, and the path is clearly marked by interpretive signs.

Today the fort itself is a grassy oval earthwork – essentially a green mound with a surrounding ditch, the remains of its medieval motte-and-bailey origins. Visitors can walk around the mound and enjoy views from the summit over the River Bann and Somerset Wood. A loop path descends from the fort to the banks of the Bann, passing the old salmon-weir called “The Cutts”. Along the way, educational panels explain the site’s layers of history (from Mesolithic camp to Norman fort). The atmosphere is very peaceful – at any time you might spot swans, kingfishers or herons along the river, or simply hear birdsong in the trees.

For those interested in the region, I’ve created an interactive map of all historical sites in North Antrim here.

Frequently Asked Questions: Mountsandel Fort

It’s an archaeological site in Coleraine, Northern Ireland, noted as one of the oldest known human settlements in Ireland. Excavations found Mesolithic huts and tools dated to about 8000 BC

Because it contains Ireland’s earliest evidence of settled life. Archaeologists uncovered flint tools and hearths showing people lived there ~9,000 years ago, long before sites like Newgrange were built.

They found circular post‑holes of wooden huts (supporting 3–15 people), as well as microlith flint tools, fish bones (eels, salmon), wild boar bones, and hazelnut shells. These remains give insight into Mesolithic diet and lifestyle.

Significant digs were done in the 1970s by archaeologist Peter Woodman. His work revealed that the site dated to around 8000 BC, making it vastly older than previously thought.

Yes. The site is a state-care historic monument open to the public with no entry fee. There’s a small car park, and visitors can walk through the wood and over the hilltop to see where the settlement once stood. (Note: it’s largely undeveloped as a tourist site, so amenities are minimal.)

- Woodman, Peter C. In: Ancient Europe, Encyclopedia of the Barbarian World, New York: Thomson and Gale, 2004. Pages 151-153. ↩︎

- Laurence Flanagan, Ancient Ireland: Life Before the Celts. Dublin: Gill and Macmillan, 2000. Page 22. ↩︎

- Jonathan Bardon, A History of Ulster. Belfast: The Blackstaff Press, 2001. Page 3. ↩︎