Last Updated: 18 August 2025

Earlier this summer I watched the road outside my home slowly broken up and resurfaced. The many weeks of hard labour (granted they took far longer than needed), disruption and chaos created, and the army of trucks carrying materials, all got me thinking about how such roads were built and used in our ancient past. For, while there wasn’t a need for our great road network, travel and trade were as critical 2,000 years ago as they are today requiring ancient roads which appear lost to time – or not.

The 5 Highways of Ancient Ireland

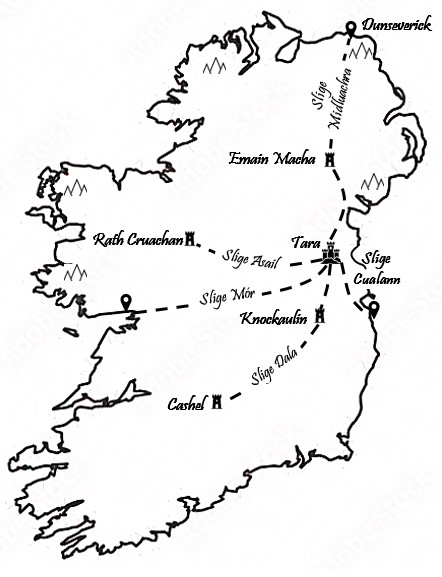

In the Lebor hUidre, or Book of the Dun Cow, there’s a passage which describes five separate roads that connected the political centre of Tara with the regions of Ireland.1 The Hill of Tara not only served as the inauguration seat of the High King, but also a religious centre due to its proximity to Newgrange, as an economic hub with the various fairs, banquets, and as a strategic centre given its location at the centre of the island. Like all capitols, it makes sense that Tara would have been a key hub for travel across the entire island.

© Daniel Kirkpatrick

Table of the 5 Ancient Highways of Ireland

| Road Name (Irish) | Translation / Meaning | Key Destinations / Termini | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Slighe Asail | “Way of the Donkey” | From Tara toward Cruachan (Rathcroghan), Connacht | Possibly linked to cattle routes or a symbolic journey west |

| Slighe Midluachra | “Way of Midluachra” | From Tara to Emain Macha (Navan Fort), Co. Armagh | Prominent in Ulster Cycle; passed through the ancient Gap of the North |

| Slighe Cualann | “Way of Cualu” | From Tara to the region of Cualu (modern Wicklow/Dublin) | Possibly a coastal or inland trade route to the Leinster coast |

| Slighe Mhór | “Great Way” | From Dublin to Galway, intersecting Tara | Believed to have cut across the island, connecting east and west coasts |

| Slighe Dála | “Way of the Assemblies” | From Tara to Cashel (Munster) via Knockaulin (Dún Ailinne) | May reference ceremonial or royal processions to southern power centres |

North to Ulster

The first road to consider is that leading north, up through the ancient capital of Ulster, Emain Macha, and then onto the Fort of Dunseverick on Ireland’s north coastline.2 This route provided a straight-highway north-south across half the island. Connecting these three settlements, it would have served an important trade route for produce and materials overland and through the various mountain passes.

This road was named Slige Midluachra, meaning ‘the way of the middle rushy place‘.

West to Connacht

To the West went Slige Asail, or Donkey trail.3 It went from Tara to Lough Owell and then north-west. I’ve drawn this heading to the ancient fort of Rath Cruachan (near modern-day Roscommon), though there’s no definitive evidence that I could find for this. However, it would seem logical that these two political centres would have been connected in such a way and the general description we are given implies as much.

Another road also travelled west, namely Slige Mhór, meaning ‘The Great Highway’. It went South-West from Tara “till it joined the Esker-Riada near Clonard, along which it mostly continued till it reach Galway.”4 This followed a series of ridges which enabled travellers to traverse over the bogland cutting right across the entire island from east to west.

South to Munster

To the South ran Slige Dala, or road of the Chief Dala. It ran through Ossory in Kilkenny and on to Cashel.5 The exact road would have, therefore, likely passed through the ancient site of Knockaulin or Dun Ailinne (or close by), as shown in the map.

This would have connected Tara with the many copper mines and other rich mineral sources from the South. It ensured a reliable trade route between the eastern and southern ports if overland travel were required.

East to Leinster

To the South-East ran Slige Cualann, or road to Cuala.6 It went from Tara through present-day Dublin, across the Liffey, and then southwards until it reached Bray. This would have connected Tara with the eastern seaboard and the many trade-routes from across the Irish sea.

Constructing Ancient Roads

While I’m sure many of us hold our present road system somewhere between merely functional to completely useless, it is not comparable to what these ancient highways. These roads were often little more than cleared paths passable only in good conditions. There were distinct stretches of impressive engineering, like the wooden walkways over bogland or bridges and fords. But these were exceptions rather than the rule.

That said, there are many references to their use by chariots and other wooden vehicles, meaning they’d have had to been at least functional for these. They would have been well maintained and likely the responsibility of local chiefs. It would have been in their interest to ensure their utility given the many economic benefits they’d have brought (something often forgotten today when it comes to transport infrastructure).

Archaeology of the Ancient Road Network

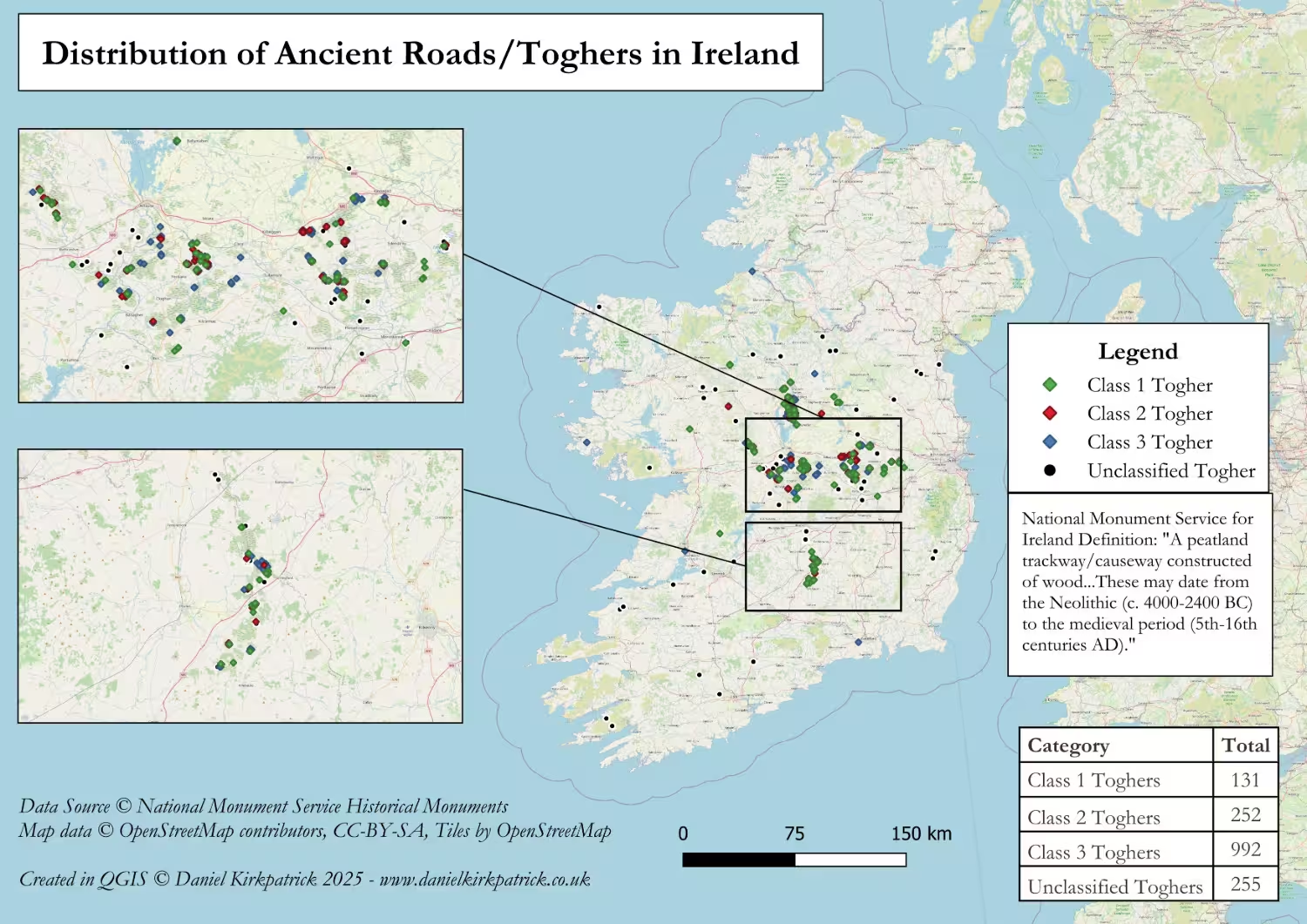

One of the most significant archaeological contributions to our understanding of ancient Irish roads comes from the study of wooden trackways or togher roads, particularly in bogland environments. These structures, made from planks, brushwood, or split timber, were often constructed to facilitate movement across otherwise impassable wetland areas. Over 1,500 of these have been recorded across Ireland, with some dating as far back as the Neolithic period (c. 4000–2500 BC).

Corlea Trackway

A notable example is the Corlea Trackway in County Longford, discovered in the 1980s. This togher, dated by dendrochronology to 148 BC, was built of oak planks laid across a corduroy foundation. It stretched for over 1 kilometre and is interpreted as a monumental construction—possibly a ceremonial or symbolic route, given its scale and apparent short period of use. Other examples, like the Edercloon complex in County Roscommon, reveal networks of wooden roads spanning several centuries and layers of use.

These trackways offer critical insights not only into engineering techniques but also into patterns of mobility and exchange. The labour-intensive construction suggests that some routes were of considerable importance, whether economically, socially, or ritually. While they may not align precisely with the legendary Slíghe routes, they demonstrate that Ireland had a sophisticated system of land travel long before the advent of stone-paved roads.

Evolution of Irish Roads

Outside of boglands, evidence for overland roads is more difficult to detect. In dryland areas, early routes may have consisted of simple beaten paths, eroded or built over in subsequent centuries. However, some early causeways and embanked roads have been excavated, particularly near major royal and ritual centres such as Tara, Emain Macha, and Rathcroghan. These are often associated with linear earthworks or alignments of standing stones, suggesting that movement and ceremony were closely linked.

By the early medieval period (c. 400–1100 AD), Ireland had developed a more formalised road system, with bóthar (roads) and slighe (ways) referenced in legal texts and property boundaries. Archaeological evidence from this period includes sunken roads or hollow ways, often deeply worn through continuous use and marked by boundary ditches. Some were reinforced with gravel or cobbles, indicating increasing concern with durability and maintenance.

Table Comparing Ancient Roads Across Cultures

| Culture / Region | Example | Construction Type | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient Ireland | Corlea Trackway (Longford) | Timber trackway over bog | c. 148 BC |

| Roman Empire | Via Appia (Italy) | Engineered paved road | From 312 BC |

| Bronze Age Britain | Sweet Track (Somerset) | Plank walkway over marsh | c. 3807 BC |

| Inca Empire (Peru) | Qhapaq Ñan | Stone-paved and stepped paths | 15th century AD |

| Ancient Greece | Sacred Way (Athens–Eleusis) | Beaten path, partially paved | Classical period |

| Medieval Ireland | Slige Midluachra (legendary) | Undefined (textual only) | Early medieval (legendary origin) |

| Han Dynasty China | Silk Road routes | Gravel and earth, some paved | From 2nd century BC |

Purpose of Irish Ancient Roads

It is easy to lose sight of the significance each of these roads had. Being able to cut East to West or North to South would have been invaluable for the economy and politics of Iron Age Ireland. These ancient highways of Ireland provided an alternative to traversing rough seas and the oft-unpredictable currents which surround this island. They also would have enabled control by chiefs and kings over the routes into and out of their territory. Think of the taxes, tribute, and trade this allowed them to manage.

Looking back on these highways gives us a sense of the connectivity which existed during this period of history. All too often it’s easy to portray Iron Age civilisations as isolated communities. But the very existence of these highways, indeed their persistence into our modern day travel routes, shows that this couldn’t have been more wrong.

Frequently Asked Questions: Ireland’s Ancient Roads

The five great roads of ancient Ireland—Slige Midluachra, Slige Mhór, Slige Chualann, Slige Dála, and Slige Assail—formed the backbone of the island’s transport system, all converging at the Hill of Tara. These roads connected ceremonial sites, royal centres, and key fording points.

Some stretches, like parts of the Esker Riada and remains of the Corlea Trackway, are accessible to the public and interpreted through visitor centres. Others survive only as place names or buried features but are often referenced in local heritage trails.

Ancient roads served multiple purposes: connecting royal sites like Tara and Emain Macha, enabling trade and cattle drives, and facilitating ritual processions. They also had symbolic importance, tying together sacred landscapes and power centres.

Most ancient Irish roads were earthen or wooden, often raised over wet ground using split oak planks or brushwood. The Corlea Trackway is a prime example of a well-engineered prehistoric timber causeway, showing advanced construction techniques.

While many of the formal road names date to the early medieval period, archaeological evidence like the Corlea Trackway in County Longford suggests wooden trackways existed as early as 148 BC, in the late Iron Age. These roads may have followed much older land-use patterns.

- See Joyce’s description of these here: https://www.libraryireland.com/SocialHistoryAncientIreland/III-XXIV-1.php ↩︎

- For a more academic discussion of this route see: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20627196 ↩︎

- This is a literal translation which is based on my very limited knowledge of Irish ↩︎

- P.W. Joyce, Available at: https://www.libraryireland.com/SocialHistoryAncientIreland/III-XXIV-1.php ↩︎

- For more see: http://www.carrowkeel.com/sites/crosses/roscrea.html ↩︎

- https://www.oxfordreference.com/display/10.1093/oi/authority.20110803095651920#:~:text=The%20area%20takes%20its%20name,way%20or%20road%20to%20Cualu. ↩︎