Ireland is full of incredible historical sites which shaped vast swathes of history, yet are forgotten to most of us today. Dundrum Castle in County Down is a prime example. Perched high above Dundrum Bay, the ruins of Dundrum Castle command one of the most striking coastal views in Northern Ireland. While once one of the most important Norman strongholds, its history dates back long into prehistory. Archaeological finds suggest that the site had been occupied for centuries — possibly as an early Christian fort or even earlier. What made it attractive to the Normans, would have been same to their ancient forebears.

This posts explores these ancient roots, contextualising the Norman site you can visit today. We will consider the surrounding neolithic monuments, early Christian artifacts, and then the history which shaped the very political formation of Ireland for centuries throughout the medieval era. But first, like with most of Irish history, we must begin with the megaliths.

Pre-Norman Origins: The Hill Before the Castle

Long before the Normans arrived in the 12th century, the strategic hill at Dundrum was already part of a much older ritual and defensive landscape. Just a short distance to the north lies the Slidderyford Dolmen, a Neolithic portal tomb dating back to around 3,500-2,500BC. It is one of numerous megalithic sites around the region, with a series further north near what is now Downpatrick, and another cluster south of the Mournes mountain range.

Like other dolmens, Slidderyford’s presence signals that this area had long held ceremonial and symbolic importance, chosen by communities millennia earlier for burial and ritual. It would have been considered sufficiently important to merit the extraordinary effort required to build such a monument. And even today, from the dolmen’s vantage point, one can see the same sweeping views over Dundrum Bay and the Mourne foothills — a reminder that this elevated ground has attracted settlement and reverence across ages.

Archaeological evidence from the hill itself1 reveals early medieval activity, with traces of an enclosed rath or fort likely constructed during the early Christian period. Such defended enclosures were typically built by local rulers or ecclesiastical communities seeking both security and visibility in a contested landscape.

Given its strategic position — commanding the coastal approaches to Lecale and within reach of Downpatrick (Dún Dá Lethglas) — it’s likely that Dundrum functioned as a local stronghold long before the Normans arrived. So when John de Courcy launched his conquest, he chose not an empty hill but a place that had served as a fortress, a symbol of local power, and a landmark in the spiritual geography of ancient Ireland.

That’s enough context though – let’s turn to the castle itself.

The Norman Conquest and Founding of Dundrum Castle

When the Anglo-Norman adventurer John de Courcy led his invasion of Ulster around 1177 AD, he pushed deep into eastern Ireland from the coast of Lecale, establishing his power base at Downpatrick. Dundrum’s commanding position above the bay — overlooking both the Irish Sea approaches and the inland routes toward Lecale and Down — made it an obvious choice for the defensive outpost of Dundrum Castle.

The earliest phase of the castle dates to the late 12th century. Archaeological surveys suggest that de Courcy may have reused existing fortifications, perhaps incorporating remnants of the earlier rath into his first bailey. References in the Annals of the Four Masters refer to to the site as Dun-droma suggesting it was already in use as a hillfort in 1147AD, providing additional evidence to support that it predated the Normans.

De Courcy arrived in Ireland following the Anglo-Norman invasion led by Henry II. Seeking land and power beyond the Pale, he led a bold, unauthorised expedition north into Ulster. Initially very successful, De Courcy captured Downpatrick and established his base there, consolidating control over eastern Ulster through a series of fortified sites including Carrickfergus and Dundrum Castle. His rule brought new administrative systems, stone castles, and religious foundations. Though initially successful and semi-independent, his power waned after rival Norman lords and the English crown moved against him, ending his dominance by the early 1200s.

So it was that Dundrum castle was soon caught up in the politics of the time. Following de Courcy’s downfall around 1203 AD, Dundrum passed to another Norman knight, to Hugh de Lacy.

Norman Fort to Mountjoy Garrison

After John de Courcy’s downfall around 1204, Dundrum Castle passed into the hands of Hugh de Lacy, Earl of Ulster. This transfer marked a turning point in the region’s political landscape. De Lacy, acting under royal authority, sought to consolidate what remained of the Norman foothold in Ulster and to strengthen English influence after years of instability.

Throughout the thirteenth century, Dundrum remained a key part of the Anglo-Norman frontier. It guarded the route between Lecale and the interior of Ulster, acting as both a garrison and administrative centre. However, the surrounding territory was never entirely subdued. Gaelic Irish families, including the Magennises and MacCartans, continued to resist Norman authority, leading to frequent skirmishes and shifting control of the region.

By the early fourteenth century, following the Bruce invasion of Ireland (1315–1318), Anglo-Norman influence in Ulster collapsed. Dundrum Castle fell into Irish hands and remained contested for much of the following centuries. It was later reoccupied and repaired by the Magennises, who adapted parts of the castle for residence rather than defence.

In the early seventeenth century, during the Nine Years’ War, Dundrum was retaken by English forces under Lord Mountjoy. It was refortified but gradually declined in military importance as the region stabilised under English rule. By the mid-seventeenth century, following the Cromwellian campaigns, the castle was largely abandoned and fell into ruin. Over time, its stones were repurposed by local builders, and nature reclaimed its walls.

Today, the remains of Dundrum Castle stand as a layered record of Norman ambition, Gaelic resilience, and the gradual transformation of medieval Ulster. Which brings us to consider these walls themselves.

Design and Architecture

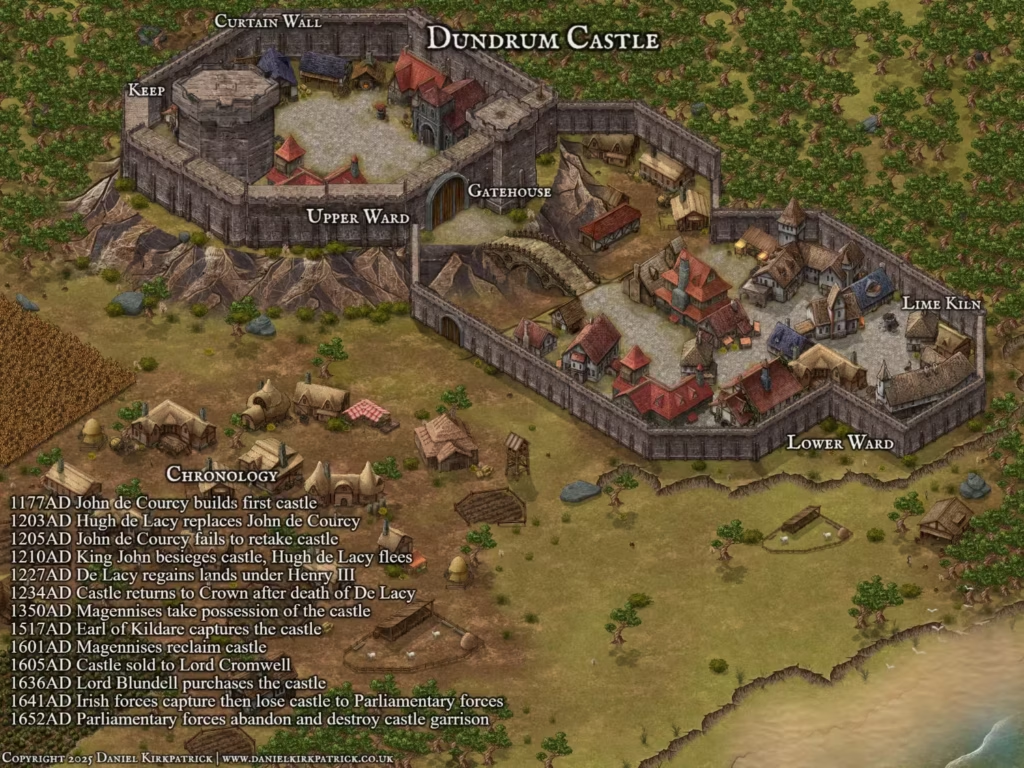

Dundrum Castle is a striking example of early Anglo-Norman military architecture adapted to the Irish landscape. Built strategically on a rocky hill with sweeping views over Dundrum Bay and the Mourne Mountains, its design took full advantage of the natural topography. The earliest stonework dates to John De Courcy in the late 12th century. It consists of a circular keep enclosed by a curtain wall, a layout typical of transitional Norman fortifications in Ireland.

The great circular keep, rising from the summit of the inner ward, was both a stronghold and a statement of power. Its walls, over three metres thick in places, were constructed from locally quarried stone bound with lime mortar. The upper levels likely contained private chambers and defensive platforms, while the lower floors served for storage and refuge. A spiral staircase within the thickness of the wall connected the levels, illustrating the careful engineering typical of early Norman masons.

Surrounding the keep stood a polygonal curtain wall with projecting towers added in later centuries. These features reflect the castle’s adaptation from a simple Norman fortress into a more complex stronghold as military technology advanced. The gatehouse, guarding the main entrance, once featured a portcullis and timber doors, while the outer ward housed stables, workshops, and lodgings for retainers.

From its commanding position, Dundrum’s architecture communicated dominance over land and sea. Its circular keep, unlike the square towers common in England, symbolised both innovation and adaptation to Irish terrain — a blend of imported Norman strategy and local practicality.

For me, however, while the architecture and design matters – it’s the day-to-day lives of the people who lived here which brings the site to life. For that, we must turn to archaeology.

Life at Dundrum Castle

Excavations at Dundrum have shed light on it’s evolution throughout the medieval period. Within the Norman layers, archaeologists uncovered lime-mortared masonry, iron nails, weapon fragments, and glazed pottery. The discovery of imported ceramics — particularly Saintonge ware from France — points to trade and contact with wider Anglo-Norman networks. These imported wares, along with high-quality masonry, reinforce Dundrum’s importance as a key military and administrative hub in Ulster’s early Anglo-Norman frontier.

One of the most interesting discoveries was a remarkably well-preserved lime kiln in the outer ward, dating to the mid- to late thirteenth century. When the kiln fell out of use, its five metres of fill became a sealed deposit of everyday refuse, preserving hundreds of artefacts that capture the castle’s working economy. These included large quantities of animal bone, oyster shell, and pottery fragments—some imported from continental Europe—indicating a diet that combined local produce with traded goods. Again reinforcing the view that this was a hub connecting medieval Ireland with the world across the sea.

Discoveries of metalwork and worked bone point to skilled craftsmanship on site, likely connected to blacksmithing, maintenance, and household repairs. The presence of iron nails, fittings, and tools suggests active construction and repair activity, while the recovery of antler and bone offcuts may reflect the production of combs or small domestic items.

Together these finds evoke a busy, semi-industrial environment supporting a critical permanent garrison.

Legacy and Visiting Today

Dundrum Castle stands today as one of the most atmospheric ruins in Ulster. Perched high above Dundrum Bay, it offers a sweeping panorama that makes clear why generations of settlers — from prehistoric Irish lords to the Normans — chose this site. Though time has exacted its toll, the ruins remains remarkably well-preserved, with the circular keep, curtain walls, and later gatehouse still outlining the castle’s formidable plan (all photographed in this post).

For all those reasons, it remains a worthwhile site to visit. The views alone are stunning on a clear day. And the history of the site certainly justifies more than passing photograph, for it embodies so much of medieval Ireland which has been eclipsed by the spectre of our more recent past.

Now managed by the Historic Environment Division, Dundrum Castle remains freely accessible year-round. There really is no excuse not to visit. But for those of you who don’t have the luxury of living within driving distance, hopefully this article will suffice. For it really is a wonderful example of a site which has endured throughout the ages.

Frequently Asked Questions: Dundrum Castle

Dundrum Castle was founded around 1177 by John de Courcy, following his conquest of eastern Ulster. It was constructed on an earlier fort site overlooking Dundrum Bay, chosen for its commanding views and natural defences.

Yes. The site is managed by the Historic Environment Division of Northern Ireland and is free to visit year-round. Visitors can explore the stone keep, curtain walls, and outer ward while enjoying panoramic views of Dundrum Bay and the Mourne Mountains.

After de Courcy’s downfall, the castle passed to Hugh de Lacy in the early 13th century. It was later occupied by the MacQuillans, Magennises, and English Crown forces, reflecting shifting power struggles in Ulster’s turbulent medieval politics.

Its strategic location allowed control over routes between Downpatrick, the Lecale peninsula, and the Mourne Mountains. From its vantage point, defenders could watch movements across Dundrum Bay and the surrounding lowlands, making it an ideal frontier fortress in medieval Ulster.

Archaeological finds show early Christian and possibly Iron Age occupation at the site, including traces of a ringfort beneath the Norman defences. Nearby, the Slidderyford Dolmen, a Neolithic portal tomb, adds evidence of prehistoric settlement in the surrounding landscape.

- Finds including iron implements, domestic artefacts, and imported pottery sherds suggest a site that was already prosperous and connected before the 12th century. ↩︎

![Dun Ailinne Excavation Photograph. Hamish Forbes. Notebook East Area 1975 Book 3 Hamish Forbes Field Notes. Text [Type]. Digital Repository of Ireland (2024) [Publisher]. https://doi.org/10.7486/DRI.ns06j259](https://www.danielkirkpatrick.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/Dun-Ailinne-Exacation-Photograph-120x120.jpg)