We all know the age-old adage that: ‘We are what we eat’. If we eat well, we feel well. If we eat and drink like there’s no tomorrow, we’ll soon regret it when tomorrow comes. Our diet individually and collectively says a great deal about the lifestyle, wealth, and social customs today. How much more so for Iron Age Ireland? For in the Iron Age, food and drink were far more than fuel. They reflected status, belief, and community. What people ate — and how they prepared and shared it — shaped everyday life.

This post explores what we know about food and drink in Iron Age Ireland. Drawing on archaeology, Irish language, and early literature, I look at farming, cooking, feasting, and the role of food and drink in society. From butter buried in bogs to banquets fit for kings, I uncover a diet rich in meaning as well as nourishment.

What did Iron Age people eat?

The Iron Age diet in Ireland was shaped by farming, foraging, and seasonal produce. Cereal grains — mainly barley and oats — were key staples. These were ground into meal and used in porridge, bread, or griddle cakes. Bread was likely cooked on flat stones or over open fires.

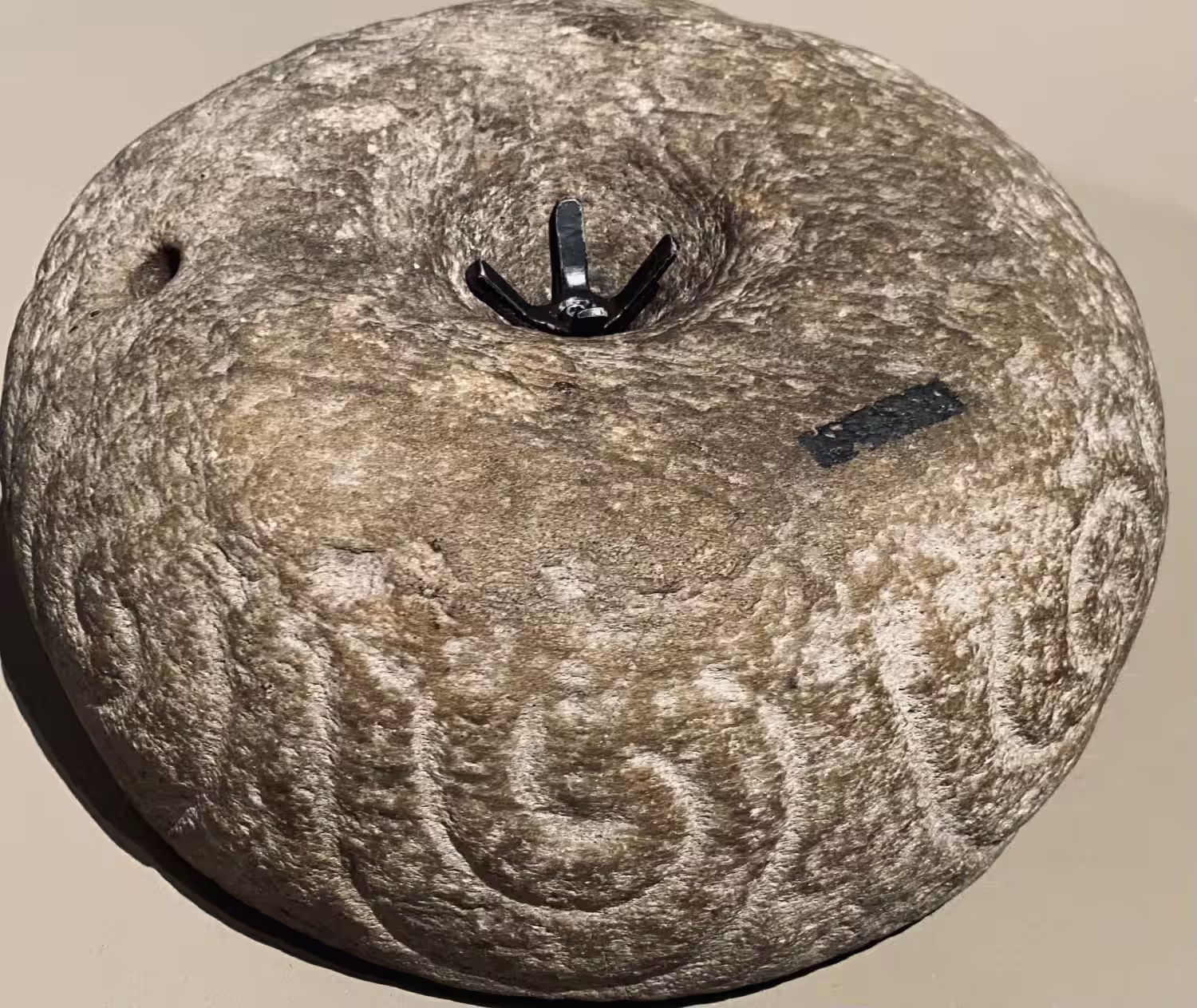

Dairy played a major role. Cattle were central to the economy, and their milk provided butter, curds, and soft cheese. The Irish word gruth refers to curds, and the tradition of milk-based foods is reflected in later law and myth. Butter was sometimes buried in bogs, possibly for storage or ritual.

Meat came from cattle, pigs, and deer. However, pork seems especially prized, appearing often in myth and feasting tales. Though there was relatively few finds of pig-bones in Ireland suggesting it was likely scarcer than the alternatives of mutton or beef. Fish and shellfish were eaten too, especially near lakes and rivers. Wild foods — hazelnuts, crab apples, bilberries — added seasonal variety.

Archaeological finds support this picture. For instance, carbonised grains, pollen data, animal bones, and cooking sites reveal a varied and often localised diet. People ate what they could grow, trade, or gather, with preferences shaped by environment and status. Moreover, the survival of words like arán (bread), im (butter), and lachta (milk) in modern Irish points to the deep roots and long continuity of these foods in Irish culture.

Iron Age foods in Ireland

| Food Type | Archaeological Evidence / Source | Prevalence |

|---|---|---|

| Barley | Charred grains in fulachtaí fia and crannóg sites (e.g. Lough Gur) | Very common |

| Emmer Wheat | Grain samples at wetland and hillfort sites (e.g. Deer Park Farms) | Common |

| Dairy (Milk, Butter) | Bog butter deposits (e.g. Glenarm, Co. Antrim), dairying tools | Widespread |

| Meat (Beef, Pork) | Animal bones at settlement sites (e.g. Navan Fort, Rathgall) | Very common |

| Wild Game | Red deer, boar, and hare bones from middens | Moderate |

| Fish | Fish bones and hooks (e.g. crannógs, riverside sites like Lough Gara) | Regionally common |

| Shellfish | Shell middens on coasts (e.g. Dún Aonghasa) | Locally common (coastal areas) |

| Hazelnuts | Charred shells in pit features (e.g. Ferriter’s Cove) | Very common |

| Honey | Literary references; possible remains of beekeeping (skep fragments) | Unclear but likely |

| Herbs | Pollen analysis and seeds (e.g. coriander, wild garlic, watercress) | Local and seasonal |

Iron Age Cooking

How we cook a meal is as important as the ingredients we use. And in the Iron Age, the Irish used a variety of distinctive methods.

First are the cooking sites known as the fulacht fiadh. These were low mounds found near water, often with a trough cut into the ground and signs of burnt stone. The most common theory is that water was heated with hot stones to boil meat. It’s likely they were also used for brewing, dyeing, or even steam cooking. Efforts to reconstruct this method have found that by adding hot stones to water they could achieve boiling water in 20 mins per pound of meat.

Second, the most common method was to use open hearths inside roundhouses. Meat might be roasted on spits or cooked in clay or bronze cauldrons. These pots have been found at crannóg and ringfort sites. Flatbreads and oatcakes could be cooked on hot stones placed near the fire.

Storage Methods

Storage was a challenge in a damp climate. Pits were dug for keeping grain dry. Dairy products may have been kept in cool, shaded places — or even in bogs, where anaerobic conditions preserved butter for centuries. The many finds of bog butter suggest both practical and symbolic reasons for this practice.

Preservation techniques included drying, smoking, and salting — especially for meat and fish. Herbs may have been used for flavour, though direct evidence is limited. Vessels made of wood, leather, or pottery helped with storing liquids and grains.

These methods reveal a society skilled in working with the land. Food wasn’t wasteful. It was seasonal, often communal, and shaped by the knowledge of what worked best in a particular place. But one food group above the others stands out – dairy.

Cattle, Status, and Dairy

Iron Age Ireland was not for the lactose intolerant – for dairy was central to diet and identity. Milk could be drunk fresh or turned into butter, curds, or soft cheese. Butter was highly valued and may have been a trade item. Seasonal cycles shaped dairy use. Cattle were milked during the warmer months, so summer and early autumn were peak times for dairy production. Lughnasadh, the harvest festival, likely featured seasonal dairy foods alongside grains and fruit.

But cattle were more than mere food – they denoted your status and wealth. They were used for meat, milk, leather, and labour — but also served as currency, dowry, and legal compensation. The more cattle a person owned, the higher their status. Brehon Law confirms this. Many laws refer to fines paid in cattle, or the number required to support a noble household. Ownership of dairy herds indicated prosperity. Some laws even regulated the grazing of cattle or the rights of herders.

Cattle also appear throughout mythology. Stories often revolve around cattle raids, prized bulls, or contests of wealth. The Táin Bó Cúailnge (Cattle Raid of Cooley) centres on the attempt to steal a famous bull — showing how livestock shaped stories as well as society.

The language reflects this central role. Terms like bó (cow), bainne (milk), and im (butter) are among the oldest in the Irish language. Together, they show how cattle were tied to food, economy, and power.

Ale, Fermentation, and Drink Culture

As you’d expect, drinks in Iron Age Ireland were typically made at home or at the level of the local community. Water was common, but fermented drinks — especially ale — had deep cultural and social roles. Ale was drunk during feasts, offerings, and daily meals.

Ale was made from barley, sometimes oats, and possibly flavoured with herbs like meadowsweet. Hops were not yet used. The brewing process likely involved heating water in large vessels, soaking grains, and allowing the mixture to ferment. Some fulachtaí fia may have been used to heat water for brewing.

Residue analysis from wooden tubs and clay pots shows traces of barley and fermentation. These finds confirm that brewing took place on a domestic and ceremonial scale. Drinking horns and carved cups from later periods suggest that drinking also carried symbolic weight.

Mead — a honey-based fermented drink — is harder to confirm archaeologically but appears in early literature. It was often associated with kingship and honour. In some tales, the rightful king was the one who received the first cup of mead at a feast.

The Irish language includes old terms for ale (coirm) and mead (mid). These appear in myths and place names, hinting at how drink was tied to landscape and memory. Together with food, drink helped define the rhythm of Irish life — from everyday gatherings to great ceremonial feasts.

Table: Drinks in Iron Age Ireland

| Drink | Evidence | Ingredients | Social Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ale (Barley Beer) | Residue analysis on pottery (Traprain Law), charred barley grains in hearths, fulacht fiadh brewing experiments | Barley, water, wild yeast | Feasting, communal gatherings, possibly ritual events |

| Mead | Literary references (e.g. Táin Bó Cúailnge, Brehon Laws); no firm residues yet | Fermented honey, water, herbs | Elite and ceremonial use, likely rare |

| Milk | Bog butter finds, faunal evidence for dairying (e.g. Navan Fort, Deer Park Farms) | Cow, goat, or sheep milk | Daily use, cooking, and symbolic in mythology |

| Herbal Infusions | Charred herb seeds (e.g. wild garlic, yarrow); early medical texts | Herbs, hot water | Medicinal and ritual purposes |

| Spring Water | Springs and wells noted in myth and settlement patterns; sacred wells | Fresh spring water | Everyday consumption; sacred in mythology (e.g. Sláine) |

Feasting and Ritual in Iron Age Ireland

Feasting in Iron Age Ireland was about more than eating. It was ritual, politics, celebration, and memory. It marked alliances, honoured the gods, and tested a leader’s generosity. Foremost amongst this, feasts followed a seasonal rhythm. The great festivals — Samhain, Imbolc, Bealtaine, Lughnasadh — each involved food rituals. At Lughnasadh, the first fruits were offered. At Samhain, cattle were slaughtered and shared. These gatherings united communities and reaffirmed shared beliefs.

Moreover, feasts marked life events from births and weddings, to victories and funerals. They often involved roasted meats, dairy, grain dishes, and ale. Who sat where and who was served what reflected a strict social order. Who drank first, what they drank from, and how much they received were matters of protocol. Indeed, law texts mention feasting rights. A noble might be owed a set amount of food or drink from their followers. Kings hosted feasts to secure loyalty. Poets were expected to praise or satirise depending on what they received.

But we can also can see these rituals if we turn to the myths which have survived.

Food and Drink in Irish Mythology

Food and drink in Irish mythology have symbolic meaning. For instance, the Dagda – the great father-figure of the Tuatha Dé Danann – possessed a cauldron known as Coire Anseasc (meaning the ‘Cauldron of Plenty’). It was said to leave no one unsatisfied, offering limitless nourishment. Those who could satisfy the hunger and needs of their people held rightful rule. The cauldron’s boundless bounty mirrored the Dagda’s role as provider, judge, and warrior, all bound into one.

In one of the best-known tales of the Fenian Cycle, the young Fionn mac Cumhaill gains wisdom not through study, but by tasting the Salmon of Knowledge, a fish that had absorbed all the world’s truths after eating hazelnuts from sacred trees. When Fionn burns his thumb cooking it and instinctively places it in his mouth, he absorbs the salmon’s knowledge. From that point on, wisdom is his whenever he bites that thumb. The episode underscores how food, even accidentally consumed, could confer insight — especially when drawn from nature.

Feasting was also tied to wealth, status, and ambition. For example, Queen Medb of Connacht, in the Táin Bó Cúailnge, is driven by a desire to equal her husband’s wealth — particularly his prize bull — because equality in possessions was seen as symbolic of equality in power. Her assertion of dominance centres around cattle raids and hosting grand feasts.

Enduring Irish Culinary Traditions

The foods of Iron Age Ireland may seem distant, but many traditions remain. Barley remains central to Irish baking and brewing, from soda breads to craft beers. Dairy — especially butter and cheese — continues to hold cultural weight, with echoes of ancient bog butter preservation lingering in rural lore.

Even cooking methods show continuity: pits and fire-heated stones survive in the memory of traditional boxty, coddle, and turf-cooked stews. Words like arán (bread), im (butter), and braon (drop or sip) reflect linguistic links to prehistoric habits. And the symbolism of food — as hospitality, honour, and heritage — remains strong in Irish life today.

Therefore, just as food in Iron Age Ireland was practical, social, and sacred, so too today. It connected people to each other and to the land. And though centuries have passed, the rhythm of eating — in season, in company, and with story — still echoes in Irish life.

Frequently Asked Questions: Iron Age food and Drink in Ireland

They ate cereals like barley and oats, dairy products such as butter and curds, and meat from pigs, cattle, and wild game. Wild fruits and nuts were also common.

Bog butter may have been a method of preservation or a ritual offering. Its burial in anaerobic bogs helped preserve it for centuries.

Yes. Ale made from barley or oats was common, and mead appears in early literature. These drinks were important in feasts and rituals.

A fulacht fiadh was a cooking site typically near water. Heated stones were used to boil water in a trough, possibly to cook meat or brew ale.