For anyone who has read Tolkien’s Fellowship of the Ring, you’ll hopefully be familiar with his haunting depictions of the Barrow-downs. Infested with undead beings called barrow-wights, this is a liminal place where the boundaries between life and death are ‘thin’. Like much of Tolkien’s genius, this concept was rooted in a rich history dating back 1,000s of years, and embodied in these enigmatic monuments which still dot our islands today. So, in this post I have created an interactive map showing the location of all known recorded barrows across the whole of Ireland so that you can explore these yourself. We then consider what barrows were, how they were used, and why they still matter today.

Interactive Map of Barrow Locations in Ireland

Interactive Map of Barrows

Click to view all recorded Barrow locations across Ireland.

This interactive map was created in ArcGIS Online using data from both Government datasets. The data was originally cleaned in Excel using PowerQuery and then in QGIS. It includes all barrow locations recorded by either government using filters for classification and description. Copyright for the data and basemaps attribution is as follows:

Data Sources

© National Monument Service Historical Monuments

© DfC Historic Environment Division & Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland Copyright 2006

Map data

© OpenStreetMap contributors, CC-BY-SA, Tiles by OpenStreetMap

What is a Barrow?

Barrows are easily identified as they are a “circular or oval raised area (generally over 1m above the external ground level) with an external fosse and sometimes an outer bank.” (National Monument Service) In other words, they are a small earthen mound surrounded by an earthen bank. One way to think of them is as an earthen equivalent to stone cairns.

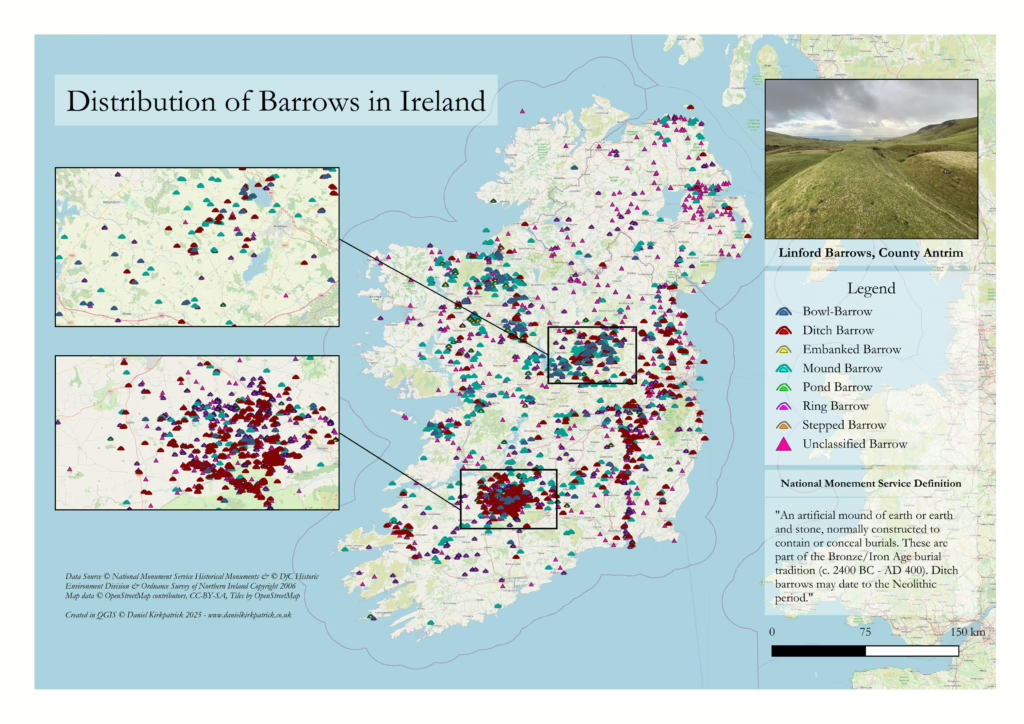

The National Monument Service distinguishes between 7 different types of barrows: bowl, ditch, embanked, mound, pond, ring and stepped. Each of these types are filtered on the map above so you can see their distribution. Regardless of type, all date to between 2,400BC-400AD – effectively in the Bronze or Iron Ages.

The various ‘types’ all relate to different physical characteristics which are fairly self-evident from their names (e.g. a bowl-barrow is like an inverted bowl). All are linked to a prehistoric burial tradition with archaeological finds supporting this interpretation.

So now we know broadly what is meant by a barrow, we then come to where they are located.

Where can you find Barrows in Ireland?

The first thing you’ll notice from the above map is the sheer scale of these monuments. They’re almost everywhere. It may look like Northern Ireland is relatively less densely populated, but I strongly expect this is a data quality issue rather than something more historically significant. But if we go down another layer, we can begin to see certain distributions.

First is the concentration near Mullingar in Westmeath, particularly around Lough Owel. This is particularly the case for bowl barrows which have the largest concentration (54) in this region. Embanked and pond barrows are relatively sparse. However, the greatest concentration is just west of Tipperary which has an overwhelming concentration of ditch barrows (515), ring barrows (1,200), and unclassified barrows (1,800). Mound barrows are concentrated in both the two regions noted above alongside near Roscommon.

I’ll be honest and confess I don’t know enough to explain why. So if you’re reading this and you do know, please get in touch.

The Linford Barrows

The Linford Barrows sit above Cairncastle in the Knockdhu Hills of County Antrim, overlooking the Irish Sea and nearby Ballygally and Larne. They form two adjacent prehistoric burial mounds, each surrounded by a ditch and earthwork, classified as ring-barrows (which you can see in the images). These features lie along an upland ridge that would have been readily visible in the Bronze Age, yet also embedded in a broader ritual-landscape of settlement and ceremony.

Both mounds are generally interpreted as Bronze Age funerary sites, likely built between about 2200 and 800 BC when barrow burial was the dominant tradition in Ireland and Britain. Cremated remains were typically placed within a wooden or stone vault at the centre of such barrows, which were then covered with earth to form low, circular mounds. One of the Linford Barrows measures roughly thirteen metres across, with the other slightly smaller.

They are overlooked by a nearby standing stone and also have several megalithic monuments in the nearby hills. Flint tools have been uncovered in the vicinity suggesting settlement of the region dates back much further into the neolithic period. Multiple cairns have been excavated too. So these barrows should be seen in the context of a much set of ancient monuments and paints a picture of a thriving community dating back 1,000s of years.

Indeed, I’d suggest if you’re interested in barrows, why not review some of my other maps of ancient monuments or posts on Irish history below.

Linford Barrows, Antrim

Click the image below to play the video.

Frequently Asked Questions: Barrows in Ireland

A barrow is a low earthen mound built to cover a burial, most often dating to the Bronze Age in Ireland.

Archaeology suggests they held single individuals or small family groups, often with grave goods.

Centuries of ploughing and land improvement flattened thousands of barrows, leaving only cropmarks or faint rises in fields.