As of the time of writing, the average UK house price is £290,000, almost 8 times the average salary. Most of us purchase our houses on credit, working 20-30 years to pay off our debt. No wonder then that we spend so much of our lives obsessing over them. It’s where we eat, play, socialise, and – more recently – work. In 1,500 years time I wonder whether our ancestors will do – like we are here – and consider what sort of lives we lived from the remains of our homes. The answer is almost certainly ‘yes’, for the buildings of today are a reflection of the way we live and what we value. So too with buildings in Iron Age Ireland.

This post explores the archaeology of Iron Age buildings in Ireland. While there are many types of buildings, here I’ll focus on three of the most significant for Ireland: roundhouses, ringforts, and crannogs. These structures offer a window into the daily life, social hierarchy, and environmental adaptation. We’ll look at what the evidence tells us about how these buildings were made, what they were used for, and how they shaped communities. But first, here’s an interactive map of all recorded crannog and ringfort sites across Ireland.

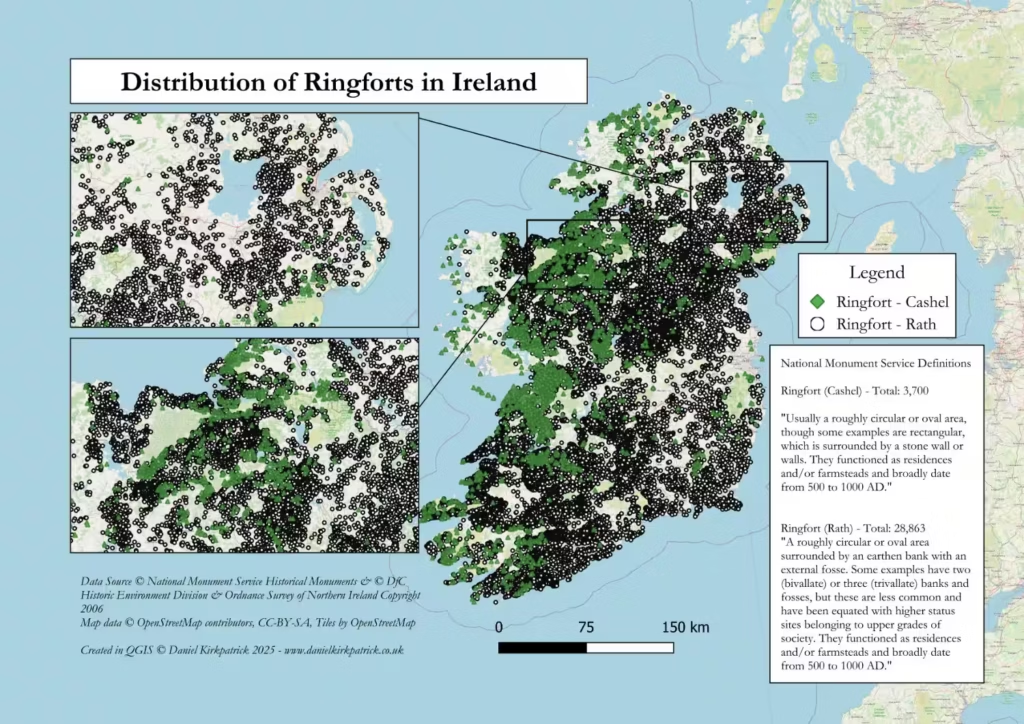

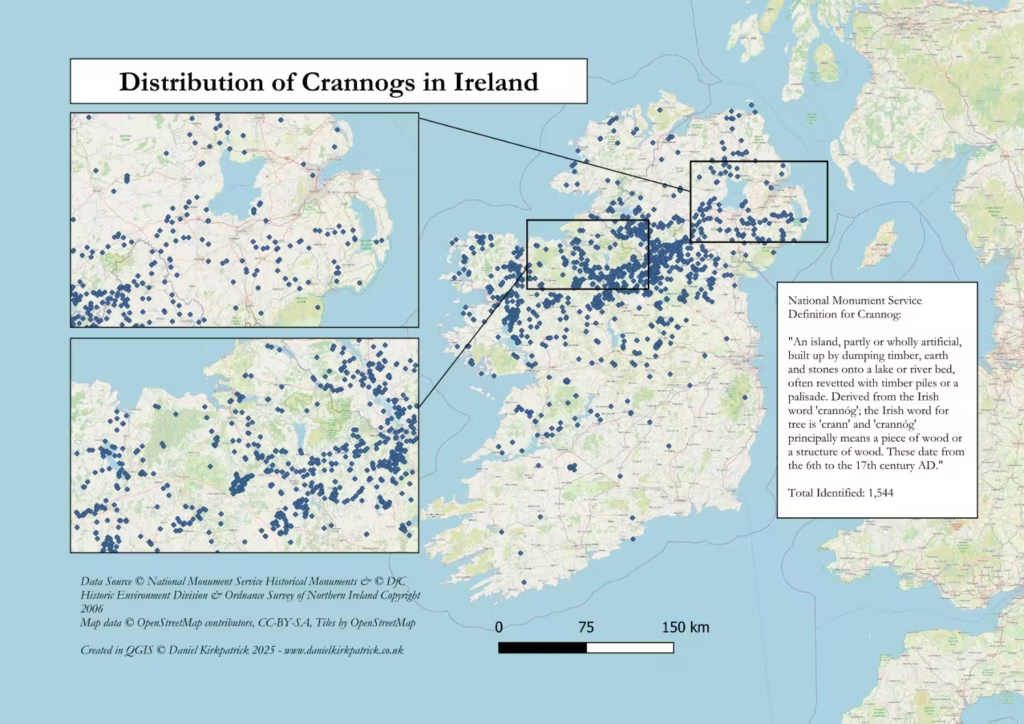

Interactive map of Ringforts and Crannogs in Ireland

This interactive map was created in QGIS using data from both Government datasets. It includes all crannog and ringfort sites recorded by either government using filters for classification and description. Copyright for the data and basemaps attribution is as follows:

Data Sources

© National Monument Service Historical Monuments

© DfC Historic Environment Division & Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland Copyright 2006

Map data

© OpenStreetMap contributors, CC-BY-SA, Tiles by OpenStreetMap

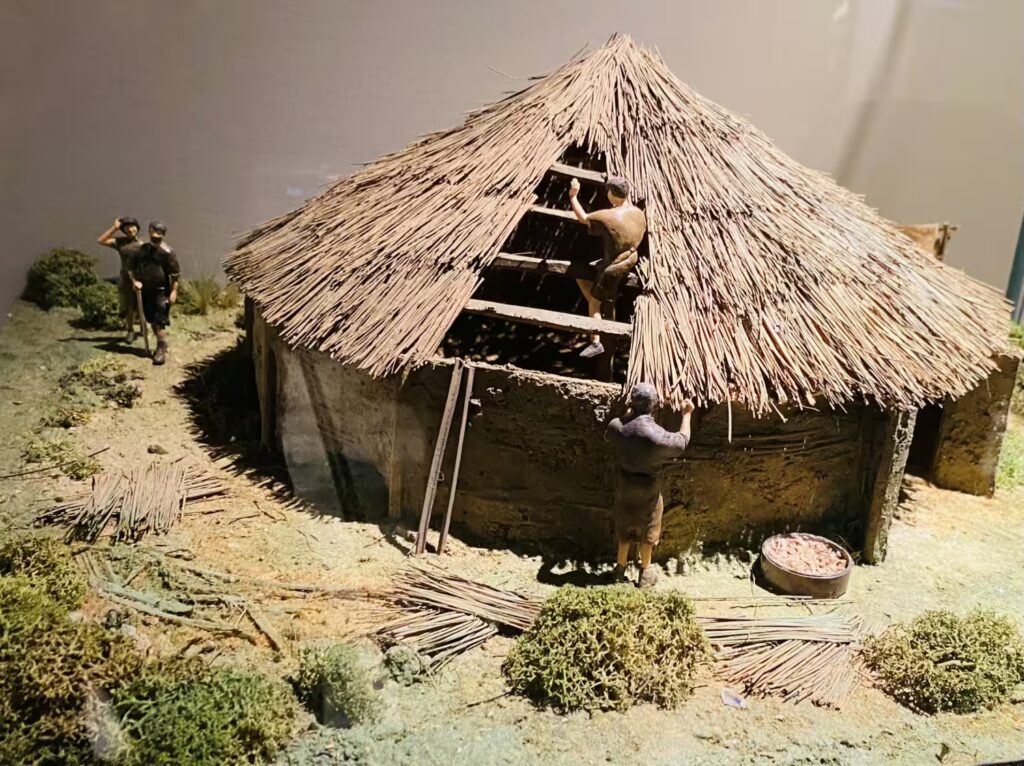

Common House Types: Roundhouses and Timber Huts

The most common domestic structure in Iron Age Ireland was the roundhouse. These circular dwellings were typically made from timber posts, wattle-and-daub walls, and thatched roofs. Some had stone foundations or revetments where timber was scarce. Postholes and floor plans survive at sites like Fort Navan in Armagh. These remains confirm circular domestic structures with defined doorways and internal divisions. Finds such as spindle whorls, quern stones, and animal bones help reconstruct the rhythm of daily life.1

Most roundhouses were single-roomed and modest in size, often between 5 to 10 metres in diameter. The entrance usually faced east or southeast. A central hearth provided warmth and light, and smoke escaped through the thatch. Inside, daily life revolved around the hearth. People slept, cooked, worked, and told stories in the same shared space. Animal pens or storage sheds may have stood nearby, forming small farmsteads.

Many of the excavations of roundhouses shows phases of settlement and reuse. They are far from an Iron Age phenomena, but should instead be seen as a continuation and evolution of existing building patterns. Examples dating back to the Bronze Age have been found at Slievemore, across Co. Cork, and Co. Westmeath, to name but a few.

Ringforts and Homesteads

From the late Iron Age onwards, many people lived in enclosed settlements known as ringforts. The National Monument Service distinctions between cashel and rath ringforts, the former being: “[A] roughly circular or oval area, though some examples are rectangular, which is surrounded by a stone wall or walls. They functioned as residences and/or farmsteads and broadly date from 500 to 1000 AD.” In contrast, rath ringforts were surrounded by “by an earthen bank with an external fosse” with variations in terms of the number of earthen banks.

But to be clear, ringforts were principally farmsteads — not defensive forts — though their defences would have clearly offered protection from raiders or wild animals. Most would have contained one or two houses, storage buildings, and animal pens. Livestock could be brought inside the enclosure at night. If interested in hillforts, you can read my research on them separately as they deserve there own post.

Some ringforts, like those at Caherconnell and Garranes, show signs of higher status. Larger size, multiple banks, imported goods, and evidence of craft production suggest elite occupation. These sites may have belonged to minor kings or important families.

Though most visible today in the early medieval period, ringforts likely began in the Iron Age and evolved over centuries. Excavations have revealed long phases of occupation and rebuilding. Their persistence into early Christian Ireland speaks to their practicality and symbolic importance.

Crannógs and Water-based Settlements

Crannógs are partially or wholly artificial islands built in lakes, rivers, or bogs. These unique sites were constructed using layers of timber, brush, and stone, often anchored with wooden piles driven into the lakebed. Dwellings were then built on top, creating secluded and defensible homesteads.

The word crannóg itself comes from crann (tree) and a suffix indicating a place or structure. It reflects the wooden nature of these constructions and their deep integration with the natural environment.

The National Monument Service for Ireland dates them to anywhere between 6th century up to the 17th century, but other sources point to much earlier examples too.

Unsurprisingly, they were often associated with high-status individuals or families. The effort required to build and maintain a crannóg points to a well-organised household with control over labour and resources. Their defensive nature also suggests there was something worthy of defending. In this way, living on a crannóg offered security, but it also symbolised prestige. These island dwellings stood apart — physically and socially — and likely served as both homes and symbols of authority.

Indeed, archaeological evidence from crannógs includes wooden platforms, walkways, and domestic artefacts. Finds like fine metalwork, decorated pottery, and imported goods suggest both wealth and wide-ranging connections. Sites often show long occupation, with phases of rebuilding over centuries.

Legacy and Continuity

The buildings of Iron Age Ireland have long since crumbled, but their imprint remains. Whether it’s the over 30,000 ringforts dotting the countryside, or 1,500 crannóg remains beneath quiet lakes, and in the shape of old place names, their presence is still felt.

Many architectural forms persisted into the early medieval period. Roundhouses evolved into timber-framed cottages. Ringforts continued to serve as farmsteads or even sacred spaces. Crannógs remained occupied in some places well into the later Middle Ages. Modern Irish architecture, especially in rural areas, reflects this deep continuity — in building materials, layouts, and even communal values. The clustering of homes, shared hearths, and connection to land and water endure.

Understanding these ancient buildings offers more than historical knowledge. It reconnects us with how people once lived — grounded, interdependent, and in tune with the landscape. These structures weren’t just shelters. They were stories, status, and belonging made visible. By tracing the stones and timber of Iron Age buildings, we uncover the foundations not just of ancient homes — but of Irish identity itself.

Frequently Asked Questions: Iron Age Buildings in Ireland

Most lived in roundhouses — circular timber huts with thatched roofs. These were clustered in small farmsteads or inside ringforts.

Ringforts were enclosed farmsteads with earthen banks and ditches. They provided protection for families and livestock and sometimes indicated higher status.

A crannóg is an artificial island built in lakes or rivers. These often housed elite families and offered security and status.

Though none survive intact, many leave clear traces in the landscape — including foundations, postholes, and place names. Some types, like ringforts and crannógs, continued into medieval times.

- There’s considerable evidence that Fort Navan was a religious site as well as royal site. But there archaeological remains of a series of roundhouses have been identified and are discussed at length in Francis Pryor’s Britain BC pp375-380. ↩︎