Last Updated: 16 December 2025

When we picture Iron Age Ireland, we often imagine scattered hillforts, small farming communities, and tribal rivalries. But beneath this surface, evidence reveals a society that was economically active and surprisingly well connected. Iron Age trade in Ireland was far more sophisticated than often imagined. Beneath the surface of scattered hillforts and tribal rivalries lay vibrant exchange networks—it was a core mechanism for survival, power, and cultural exchange.

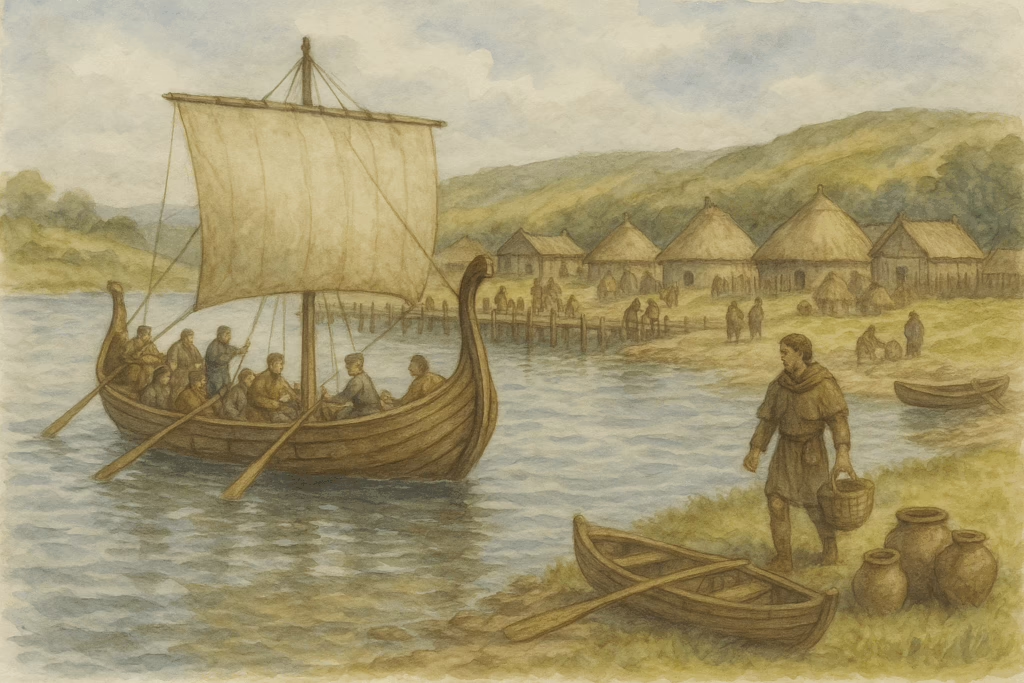

Despite the absence of coinage or cities, communities exchanged goods through well-established networks. Rivers, bog trackways, and coastal routes formed a framework that connected local túatha and linked Ireland to the wider world. Farmers bartered cattle and grain. Artisans traded tools, weapons, and ornaments. Foreign objects like glass beads and amber reached Ireland from across Europe, often through complex chains of exchange.

This post explores how trade shaped Iron Age Ireland. We’ll examine the economic foundations of local life, the role of elite-controlled redistribution, and the evidence for long-distance contact. From inland trackways to foreign luxury items, we’ll see that Iron Age Ireland was not an isolated outpost—it was part of a dynamic, interconnected landscape, where trade played a vital role in shaping power and identity.

The Economic Landscape of Iron Age Ireland

The economy of Iron Age Ireland was deeply rooted in land, livestock, and local production. While there was no coinage, urbanisation, or formal marketplaces, this did not mean Ireland lacked economic complexity. Instead, the economy functioned through a mix of subsistence farming, reciprocal exchange, and elite redistribution. People lived in dispersed rural settlements, often centred around ringforts or farmsteads. These communities were self-sufficient in food but relied on trade and exchange for tools, raw materials, and prestige goods.

Cattle were the backbone of wealth and status. Ownership of herds signalled prosperity and influence. Cattle served not just as food but as currency, tribute, and legal compensation. Many fines or agreements—later recorded in the early medieval Brehon Laws—were paid in livestock, reflecting much older traditions. Wealth was often measured not by coin, but by the ability to command cattle, land, and people. This pastoral economy created strong interdependence between households and between túatha (tribal units).

Ironworking was another key element of economic life. Blacksmiths produced tools for farming, weapons for defence, and decorative metalwork for social display. These objects were exchanged locally or passed upward through the social hierarchy as tribute or gifts. In a world without cash, production and redistribution were tightly bound to personal relationships, kinship obligations, and seasonal gatherings. Status was reinforced not only by what one owned, but by what one could give away.

The Iron Age economy in Ireland was therefore not primitive or static. It was adaptive, decentralised, and embedded in social and political life. Goods moved not only for practical use, but to bind people together. Trade, whether of cattle, grain, or bronze ornaments, was a way to reinforce alliances, settle disputes, and express power.

Local Trade and Internal Networks

Trade within Iron Age Ireland operated along well-worn paths, not just through geography but through social practice. Communities across the island exchanged goods regularly—between túatha, between farming households, and between elites and their dependents. This internal trade system did not rely on coinage or central marketplaces. Instead, it functioned through networks of obligation, hospitality, and seasonal gatherings that fostered both economic exchange and political cohesion.

Rivers served as Ireland’s earliest highways. Major waterways like the Shannon, Boyne, and Erne offered relatively efficient transport for bulky or heavy goods. Boats, rafts, or log canoes could carry supplies from inland farms to coastal gathering points. Where the land was wet or unstable, communities constructed wooden trackways—some of which survive today. The best known is the Corlea Trackway in County Longford, dated to around 148 BC. This massive timber causeway, laid through a bog, demonstrates that considerable resources were invested in overland transport, likely for both practical and ceremonial purposes.

Seasonal Festivals and Trade

Seasonal assemblies also played a major role in facilitating trade. These events, which often took place at ceremonial centres or tribal borders, allowed people to gather, exchange goods, form alliances, and renew social ties. At such fairs, a farmer might trade livestock or grain in return for iron tools, salt, or woollen cloth. Skilled craftspeople—such as blacksmiths, weavers, or potters—likely sold or exchanged goods directly to elites or their representatives.

Elites managed and benefited from these networks. They acted as brokers of goods and protectors of trade routes. By hosting feasts and redistributing goods at large gatherings, they reinforced their authority and extended their influence. This redistribution was both practical and symbolic—it allowed elites to demonstrate their generosity and power, while also ensuring access to key resources within the community.

Trade, in this context, was not simply economic. It was a system bound up with political relationships and ritual practice. The movement of goods—whether across rivers, roads, or social hierarchies—reinforced the structure of Iron Age society, linking everyday survival to the performance of status and community belonging.

Table: Internal Trade Goods and Routes

| Goods | Likely Source | Transport Method | Use or Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | Pastoral communities | Herded overland | Wealth, food, status |

| Iron tools | Local blacksmiths | Carried or carted | Agriculture, construction |

| Salt | Coastal settlements | Traded inland | Preserving meat and dairy |

| Textiles | Local households | Exchanged at gatherings | Clothing, status displays |

| Grain | Arable farms | Local exchange | Food and tribute |

International Connections and Imported Goods

Although Iron Age Ireland lay on the periphery of Europe, it was by no means cut off from the wider world. Archaeological finds reveal that Irish communities were part of long-distance exchange networks that stretched across Britain, the Atlantic coasts, and into continental Europe. These connections brought prestige goods into Ireland—objects that were rare, exotic, and politically valuable. While direct control of seaborne trade remains uncertain, the presence of foreign items in high-status contexts strongly suggests consistent, if selective, international contact.

Iron Age Imports to Ireland

Among the most striking of these imports are glass beads, often found in burial or ritual settings. These brightly coloured objects were not produced in Ireland. Their origins lie in workshops in southern Britain or the continent, likely in regions influenced by Roman or pre-Roman industry. Their distribution across Irish sites points to a demand for prestige adornments that carried both aesthetic and social meaning. In Iron Age societies where status was performed visually, imported items signalled both wealth and connection.

Amber is another key indicator of long-distance exchange. Mined in the Baltic region, amber travelled through a series of trade nodes before arriving in western Europe. Its discovery in Irish contexts—though relatively rare—confirms that Irish elites participated in far-reaching exchange systems. Amber was not just decorative; in many societies it held ritual or symbolic power, adding to its value as a diplomatic or elite good.

Metal objects also show external influence. Some La Tène-style ornaments, including brooches and weapons, appear in Ireland, particularly in eastern and southern regions. Whether imported directly or copied locally, these items demonstrate contact with Celtic-speaking regions of Gaul and Britain. In some cases, such as spiral-decorated torcs or scabbards, continental styles were reworked in distinctly Irish forms—suggesting both imitation and adaptation.

What did Ireland offer in return?

Though archaeological evidence is limited, it is likely that Ireland exported animal hides, wool, and possibly gold, along with livestock or even slaves. These goods were abundant within Ireland and would have been valuable to neighbouring communities. Irish metalwork itself, especially gold, was renowned in earlier periods and may have remained a desired commodity.

Some coastal sites, such as Drumanagh and Lambay Island, have produced Roman artefacts, including coins, amphorae, and brooches. These finds raise the possibility that these locations served as trading outposts or points of contact with Roman Britain. Whether through raiding, gift exchange, or diplomacy, these Roman goods made their way into elite Irish circles—adding to the prestige economy and reflecting Ireland’s indirect role in the Roman world.

Far from being isolated, Iron Age Ireland engaged selectively with broader trade systems. The goods that entered were more than material—they were markers of power, identity, and international awareness in a society that knew the value of what came from beyond its shores.

Control, Elites, and the Politics of Exchange

In Iron Age Ireland, trade was not a neutral or evenly distributed process. It operated within a social and political structure in which power and prestige were concentrated among elite groups. These elites—chieftains, kings, or high-ranking members of tribal lineages—played a central role in directing and controlling the flow of goods, both within and beyond their territories. Access to exotic or high-status items was closely tied to elite authority, and the distribution of such goods was a key tool in maintaining loyalty, asserting dominance, and reinforcing social hierarchies.

Imported items such as glass beads, amber, and continental-style metalwork rarely appear in everyday domestic settings. Instead, they are found in ritual deposits, hoards, and ceremonial sites—places associated with symbolic power and elite control. These goods were not just commodities; they were political instruments. Possessing and redistributing rare items allowed leaders to create bonds of allegiance. When given as gifts, these objects expressed generosity and superiority. When displayed, they signalled a connection to distant lands and the ability to command resources far beyond the local economy.

Politics of Trade

Some foreign items may have entered Ireland as diplomatic offerings or marriage gifts, while others could have been acquired through raiding or alliance-building. Regardless of their source, such items passed through the hands of elites who used them to strengthen their own position. Control over trade routes—whether overland, riverine, or coastal—also added to a ruler’s strategic power. A chieftain who controlled access to a harbour or assembly site could influence not only economic activity but political negotiations as well.

This politicisation of trade helps explain why Iron Age economies are difficult to map in modern terms. Economic activity was never purely transactional; it was part of a broader social fabric in which status, obligation, and display were constantly negotiated. In this world, the elite were not just consumers of luxury goods—they were the gatekeepers of exchange itself.

Transition to the Early Christian Period

The arrival of Christianity in Ireland during the fifth century AD marked a cultural transformation, but it did not bring an abrupt break with Iron Age economic practices. Instead, many of the structures and behaviours associated with trade—such as redistribution, elite control, and long-distance contact—persisted, though now shaped by new institutions and religious ideologies. As political power became increasingly aligned with Christian leaders and monastic communities, the centres of exchange shifted from royal sites to monasteries, which soon emerged as focal points of both spiritual and economic life.

Monasteries were not only places of worship; they were also economic hubs. They collected tribute from lay communities, managed agricultural production, and oversaw craft industries. In many cases, they became storehouses of wealth—accumulating livestock, grain, precious objects, and manuscripts. Some of these goods were redistributed to local communities or exchanged with other monastic houses, continuing the patterns of reciprocity and status-driven exchange that had defined Iron Age society. At the same time, monastic scribes began to record legal and economic transactions, introducing literacy into economic life and altering how value and obligation were documented.

The Merchant Monks of Ireland

Contact with the outside world intensified during this period. Irish monks travelled abroad, and foreign clergy arrived in Ireland. Along with them came goods such as wine, books, reliquaries, and metalwork, many of which were not locally produced. These imported items, like the Roman and continental artefacts of earlier centuries, reinforced the prestige of those who owned or displayed them. Ireland also became an exporter—not only of raw materials like hides and wool, but of intellectual and religious culture. Irish scholars, missionaries, and craftsmen played active roles in Christian Europe, and their movement sustained cross-channel and cross-continental exchange.

While the Iron Age had lacked coinage, the early Christian period saw a slow adoption of monetary systems, particularly in areas with strong British or continental connections. Even so, barter remained dominant for many everyday exchanges. Economic life remained local and kin-based in structure, but it was now embedded within a Christian worldview and a literate, ecclesiastical framework.

In this period of transition, we can see not the replacement of one economy by another, but the transformation of trade practices within a changing social order. The influence of Iron Age exchange patterns persisted beneath the surface, even as Ireland entered a new era of faith, writing, and expanded horizons.

Conclusion

Trade in Iron Age Ireland was not a marginal activity—it was central to how society functioned. Far from being an isolated or inward-looking culture, Ireland was part of a network of exchange that linked households, túatha, and distant lands. Goods moved not through formal markets or coins, but through relationships built on trust, status, and shared custom. Whether in the form of cattle exchanged at seasonal gatherings or foreign ornaments gifted between elites, trade helped shape the political and social fabric of the island.

The archaeology paints a picture of a decentralised economy where power and wealth were deeply tied to control over resources and redistribution. Elites leveraged trade to display their influence, strengthen their alliances, and maintain their authority. Imported items such as amber, glass, and La Tène metalwork were more than decorative—they were tokens of a wider world and tools of social performance.

This dynamic economy did not vanish with the arrival of Christianity. Instead, it evolved. Monastic centres absorbed the roles once held by royal sites, and trade continued along familiar paths, now guided by the hands of clerics and chroniclers. The rhythms of exchange endured, even as the spiritual and intellectual life of Ireland transformed.

In tracing these patterns, we uncover a richer view of Iron Age Ireland—one not defined by isolation or simplicity, but by movement, adaptation, and enduring ties. Trade was not just about goods. It was about meaning, identity, and the shaping of an interconnected world at the western edge of Europe.

Frequently Asked Questions: Iron Age Trade in Ireland

They traded cattle, textiles, tools, foodstuffs, and imported luxury items like beads, amber, and bronze.

Yes. Internal routes used rivers and timber trackways, while coastal forts likely supported international trade.

Local elites or chieftains controlled access to goods and redistributed items to reinforce their authority.

Indirectly. Irish goods reached Roman Britain and vice versa, though Ireland remained outside the empire.