In the early medieval centuries, Ireland developed a distinct form of Christianity—monastic, locally rooted, and led not by diocesan bishops but by charismatic founders. Among these figures, St Brendan of Clonfert stands out as both a historical abbot and the subject of one of the most captivating legends in European religious tradition.

Brendan’s story straddles two worlds. On the one hand, he was a real 6th-century monk whose foundation at Clonfert became a pillar of Irish Christian life. On the other, he became the central figure in the Navigatio Sancti Brendani, a fantastical voyage narrative that cast him as a seeker of paradise across the Atlantic. Understanding Brendan requires holding both threads in tension—what archaeology and early sources can confirm, and what later medieval imagination celebrated.

This post explores Brendan’s life and legacy, from his early education and monastic foundations to the legendary voyage and enduring influence. Along the way, we’ll examine what the historical record reveals, where myth begins, and how Brendan’s name became inscribed in Ireland’s sacred landscape—from Clonfert and Ardfert to Mount Brandon and beyond.

Early Life and Education of St Brendan

St Brendan was born around AD 484–490 near Tralee in County Kerry, into the Corco Duibne—a Gaelic lineage with royal ties in the Dingle Peninsula. Though firm records are lacking, later hagiographies and local traditions preserve key details of his early life. Brendan’s parents were Christian, reflecting the growing reach of the faith into elite Gaelic households by the late 5th century.

According to tradition, he was baptised at Tubrid, near Ardfert, and given the name Bréanainn, possibly meaning “teardrop” or “prince.” His spiritual education followed a path typical of early Irish saints: fosterage under female saints, then study under major monastic teachers. He was first entrusted to St Íte of Killeedy, revered as the “Brigid of Munster,” who nurtured several future founders. Around age six, Brendan is said to have studied under St Jarlath of Tuam, and later under St Finnian of Clonard, joining the generation known as the Twelve Apostles of Ireland—those who helped shape the island’s monastic future.

While these early associations rest on later sources and genealogies rather than contemporary annals, they place Brendan firmly within the interconnected monastic network that defined 6th-century Irish Christianity. By the age of 26, according to tradition, he had been ordained a priest—the first concrete milestone in a career that would soon mark the Irish landscape with enduring ecclesiastical foundations.

Table: Timeline of St Brendan’s Life

| Event | Approx. Date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Birth near Tralee | c. 484–490 | From later saints’ Lives |

| Baptism at Tubrid | Late 5th c. | Linked to Tubrid well |

| Founding of Clonfert | c. 563 | Later rebuilt as a cathedral |

| Alleged Atlantic Voyage | 6th c. (legend) | Symbolic Christian allegory |

| Death and Burial | c. 577–578 | Site of grave uncertain |

Ministry and Monastic Foundations

Brendan’s historical legacy rests above all on the monastic communities he founded across Ireland. These were not minor hermitages but influential centres of religious life—places that shaped Ireland’s spiritual geography for centuries. Among them, two stand out: Clonfert, his principal foundation, and Ardfert, the traditional seat of his activity in Kerry.

Clonfert: Brendan’s Chief Foundation

Brendan’s most enduring work began at Clonfert in County Galway, founded—according to later sources—around AD 563. Though not mentioned in the contemporary annals, the date fits the broader pattern of Irish monastic expansion in the mid-6th century. By the 12th century, Clonfert was well-established as a major Christian centre: at the Synod of Rathbreasail (1111), it was named the cathedral seat for the region.

The site remains one of the most visually striking in Irish ecclesiastical heritage. The 12th-century Romanesque cathedral—particularly its ornate west doorway—is celebrated as a masterpiece of Irish stone carving. Archaeological evidence confirms this cathedral stands on an earlier monastic enclosure, with activity dating back to Brendan’s lifetime. Though the wooden structures of the original foundation are long gone, the continuity of Christian worship at Clonfert speaks to the strength of Brendan’s influence.

By later tradition, Brendan served as Abbot of Clonfert, leading a community that likely included dozens of monks. These men would have followed a typical Irish monastic rule—combining prayer, study, craft, and agricultural labour. Excavations at sites like Nendrum (County Down) reveal what such communities may have looked like: tide-powered mills, metalworking workshops, and areas for manuscript production. It is plausible that Brendan’s monks built boats, copied texts, and maintained Clonfert as both a spiritual and economic hub. The now-lost title recorded on his tomb—Abbas Multorum Locorum (“abbot of many places”)—reflects the reach of his foundations.

Ardfert and the Southern Legacy

Brendan is also intimately associated with Ardfert, near his native Tralee. The name itself—Árd Fheidharta—is sometimes translated as “Brendan’s height,” and tradition holds that he founded a church there in the early 6th century. While the existing ruins date largely from the 12th–13th centuries, they sit on a site with strong claims to early Christian activity.

The Corpus of Romanesque Sculpture in Britain and Ireland affirms the tradition: “The site [at Ardfert] was founded by St Brendan of Clonfert.” By 1152, Ardfert had become the seat of the newly established Diocese of Kerry, confirming its ecclesiastical importance. Today, the ruins of Ardfert Cathedral preserve Romanesque doorways, medieval tombs, and Gothic tracery—layers of history built on Brendan’s early foundation.

The Voyage of St. Brendan the Navigator

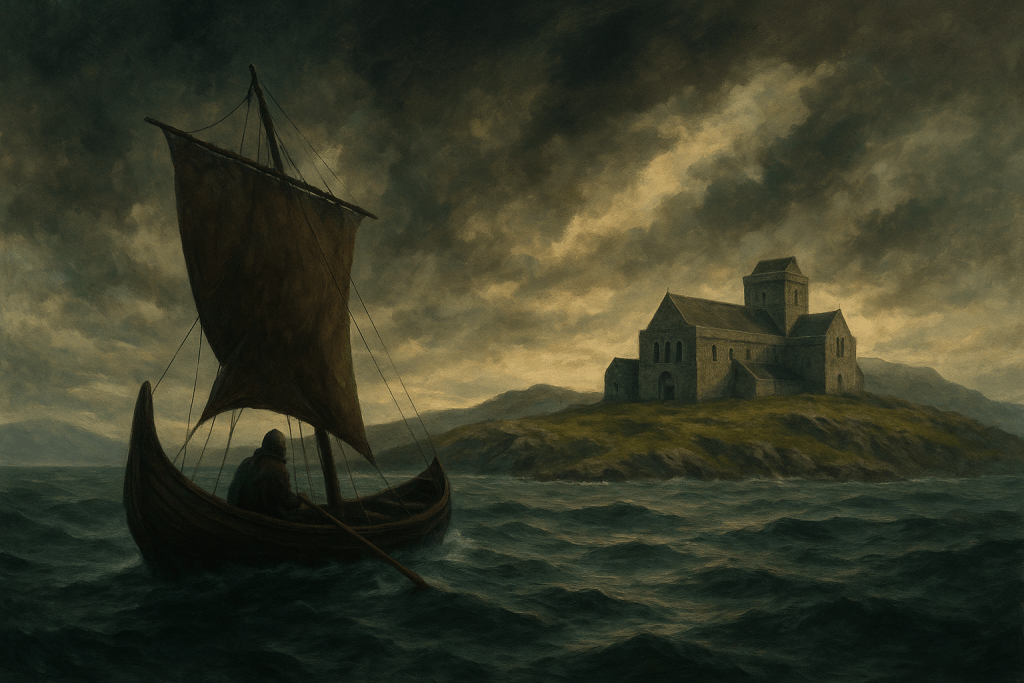

Perhaps the most famous story associated with Brendan is not grounded in history, but in spiritual imagination. The Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis (Voyage of Saint Brendan) is a medieval Latin tale that blends Christian allegory with maritime adventure. While it brought Brendan lasting fame as “The Navigator,” historians treat the text as religious literature rather than historical record. Indeed, there is considerable overlap with the mythological tale of Bran and his voyage linked to the Irish god Manannan.

The Voyage as Legend and Spiritual Literature

Composed in the 9th century—with manuscripts circulating widely across medieval Europe—the Navigatio tells of an elderly Brendan who sets sail with fellow monks in search of the Terra Repromissionis Sanctorum (“The Promised Land of the Saints”). Over seven years they encounter marvels: talking birds, floating crystal palaces, sea monsters, and a whale so vast they mistake it for an island.

Each of these elements carries symbolic meaning. The voyage serves as a spiritual allegory, mapping the monastic journey through temptation, trial, and divine revelation. Scholars compare it to both earlier Irish immrama (voyage tales) and Christian pilgrimage narratives. As such, the Navigatio is less about navigation than it is about faith, perseverance, and divine grace.

The tale was wildly popular. It survives in over 100 medieval manuscripts and was translated into Old French, Middle Dutch, German, and even Icelandic. By the 12th century, it had become part of Europe’s literary canon of saintly travels—often compared to the journeys of Moses, Aeneas, or Odysseus. Some later versions even claim Brendan reached distant lands across the Atlantic, inspiring speculative maps that featured “St Brendan’s Island”.

Historical Assessment of the Voyage

Despite its cultural popularity, no historical evidence supports the idea that Brendan sailed to North America or any distant Atlantic land. Claims linking Brendan to Iceland, Greenland, or the Americas are based entirely on imaginative readings of the Navigatio and later romantic retellings—not on reliable sources.

Modern historians are clear: the Navigatio is a spiritual voyage narrative, not a navigational account. It was likely composed by an Irish or Continental monk in a literary tradition of visionary seafaring, with parallels in Celtic myth (like the Isle of Apples or Tir na nÓg) and Christian eschatology (paradise beyond the sea).

While the voyage cannot be treated as historical fact, its legacy is significant. It shaped medieval conceptions of exploration, influenced early Christian understandings of paradise, and reinforced Brendan’s identity as a model pilgrim. Even mapmakers in the Age of Discovery included Brendan’s Island on charts—testimony not to his travels, but to the enduring appeal of the story.

Today, the Voyage of St Brendan is best understood as a work of imaginative faith, reflecting Ireland’s fusion of maritime culture, Christian devotion, and mythic storytelling. It adds depth to Brendan’s legacy, even as we keep it distinct from his more historically grounded contributions.

Archaeological Evidence and Historical Legacy

Though few contemporary records of Brendan survive, the archaeological footprint of his legacy is clear. His most enduring contributions lie not in manuscripts or miracles, but in the monastic communities he founded—particularly at Clonfert and Ardfert—which served as centres of worship, learning, and local authority for centuries.

Clonfert Cathedral and Brendan’s Foundations

The strongest archaeological link to Brendan is at Clonfert, County Galway. Tradition holds that Brendan founded a monastic community here around AD 563, and while early records are sparse, the site’s importance is undisputed. By the 12th century, Clonfert had become a cathedral city and diocesan centre, as confirmed by the Synod of Rathbreasail (1111) and Synod of Kells (1152).

The 12th-century Romanesque cathedral that now stands at Clonfert is among Ireland’s finest. Its elaborately carved west doorway—featuring animal heads, human faces, and geometric motifs—is a masterpiece of Irish Romanesque architecture. Though later than Brendan’s time, it stands on the site of his original monastery. Inside, the cathedral houses medieval tombs and inscriptions that attest to the site’s long ecclesiastical use.

Archaeological surveys have also uncovered traces of earlier settlement—enclosures, graves, and artefacts—suggesting continuous occupation from the 6th or 7th century onward. While no relics of Brendan himself have been found, the continuity of worship, the persistence of his name, and the location’s prominence all affirm its historical connection to him.

Ardfert and the Sacred Landscape of Kerry

In County Kerry, Brendan is closely linked to Ardfert, where local tradition holds he founded another monastic site. The name Árd Fhearta (“height of miracles” or possibly “Brendan’s height”) reflects this long-standing association. Although most visible remains date from the 12th–13th centuries, scholars agree that Ardfert was originally a 6th- or 7th-century foundation.

The ruins of Ardfert Cathedral today include Romanesque and Gothic elements, alongside traces of earlier ecclesiastical enclosures. The site continued to serve as the seat of the Bishop of Kerry into the late medieval period. Brendan’s memory remains alive here in local dedications, pattern days, and historical references to him as the patron of the region.

Pilgrimage and the Mythic Landscape

Beyond church buildings, Brendan’s legacy lives on in Ireland’s sacred geography. The peak of Mount Brandon (952 m) in west Kerry—named after the saint—became a medieval pilgrimage site, associated with his legendary voyage. Pilgrims walk the St Brendan’s Path to the summit each year, especially on May 16, Brendan’s feast day.

Though the pilgrimage developed long after Brendan’s death, its endurance speaks to how deeply his legend was woven into the land. Similar patterns can be seen in place-names (Brandon Hill, Brandon Creek), early cross-slabs, and medieval graffiti bearing his name—signs of a memory cherished across centuries.

In short, while the Navigatio is legend, the foundations Brendan left behind are real. His monasteries evolved into cathedrals, his pilgrimage sites endured, and his name was carved into the landscape itself. Through these physical traces, we find the enduring presence of a man whose spiritual influence outlasted the age of saints.

Table: Comparison between St Brendan and other Irish Saints

| Saint | Life Dates (approx.) | Chief Monastic Foundation | Known For |

|---|---|---|---|

| St Brendan of Clonfert | c. 484–578 | Clonfert (Co. Galway); also Ardfert (Co. Kerry) | Monastic founder; legendary Atlantic voyage |

| St Patrick | Active mid–late 5th century (d. c. 461) | Armagh (symbolically); actual missionary across north and west | Ireland’s patron saint; missionary credited with converting much of the island |

| St Brigid of Kildare | d. c. 525 | Kildare (Cill Dara – “church of the oak”) | Female monasticism, healing miracles, generosity, wisdom |

| St Columba (Colum Cille) | 521–597 | Iona (Scotland); also Derry, Durrow | Exile, missionary to Scotland, role in Christianising Picts |

| St Ciarán of Clonmacnoise | d. c. 549 | Clonmacnoise (Co. Offaly) | Monastic school and scribal culture |

Brendan’s Enduring Legacy

St Brendan of Clonfert stands at the crossroads of history and legend. As a historical figure, he was a 6th-century monk and abbot who founded enduring Christian communities in the west of Ireland. His principal monasteries at Clonfert and Ardfert became long-lasting centres of faith, education, and regional authority—places that retained their sacred role well into the high Middle Ages. Archaeological evidence, from the Romanesque grandeur of Clonfert Cathedral to the ruins of Ardfert and the pilgrim paths of Mount Brandon, affirms his tangible contribution to Ireland’s monastic heritage.

Yet Brendan’s legacy extends beyond stone and soil. Through the Navigatio Sancti Brendani, his name sailed into the realm of story, imagination, and spiritual longing. The tale of his Atlantic voyage—though never intended as historical fact—became a symbol of Christian pilgrimage, monastic devotion, and the search for divine truth. It placed Ireland’s early saints on a mythical map that stretched from the western seaboard to the edges of paradise.

In this way, Brendan embodies the two great currents of early Irish Christianity: the discipline of the monastery and the dream of the open sea. His life reminds us that faith in medieval Ireland was lived not only in prayer and silence, but in movement, exploration, and the reimagining of the world through story. Whether as founder, pilgrim, or navigator, Brendan left a legacy that shaped Ireland’s sacred geography—and continues to inspire those who walk in his footsteps.

Frequently Asked Questions: St Brendan of Clonfert

St Brendan of Clonfert was a 6th-century Irish monk and abbot best known for founding the monastery at Clonfert in County Galway. He was one of the most prominent early Irish saints and is also remembered in legend as Brendan the Navigator.

Brendan founded several monastic communities, most notably Clonfert and Ardfert. He played a key role in the spread of early Irish Christianity and is considered one of the “Twelve Apostles of Ireland,” a group of early monastic founders.

The tale of Brendan’s Atlantic voyage comes from the Navigatio Sancti Brendani, a 9th-century spiritual allegory. While it inspired later exploration legends, there is no historical evidence Brendan reached the Americas or any far western land.

Key locations include Clonfert Cathedral in County Galway, Ardfert Cathedral in County Kerry, and Mount Brandon, a major pilgrimage site linked to Brendan’s legend. These places preserve both historical ruins and local traditions tied to his life.

Brendan is honoured as a patron of sailors and voyagers. His feast day (16 May) is celebrated in Catholic, Anglican, and Orthodox traditions. His story blends monastic history with Irish myth, making him a lasting symbol of spiritual journey and exploration.