From gods to a mythical race, the Irish Aos Sí have become a myth about a myth. They are a reflection of an ancient narrative which has been morphed by modern culture. But the real myth is far more compelling than our modern inventions. Whether it’s their roots in the Tuatha de Dannan, their relationship with the ‘otherworld’, or their evolution into the lore surrounding fairy mounds, the Aos Sí are part of the very culture and land of Ireland. With the references to the Aos Sí appearing as early as the 8th century – in saga literature like Echtrae Chonnlai – their presence in Irish history remains one of the oldest and most enduring.

From etymology to mythical sagas, from ancient comparisons to contemporary interpretations, this post sets out the origins, folklore and legacy of the Aos Sí.

Etymology of the Aos Sí

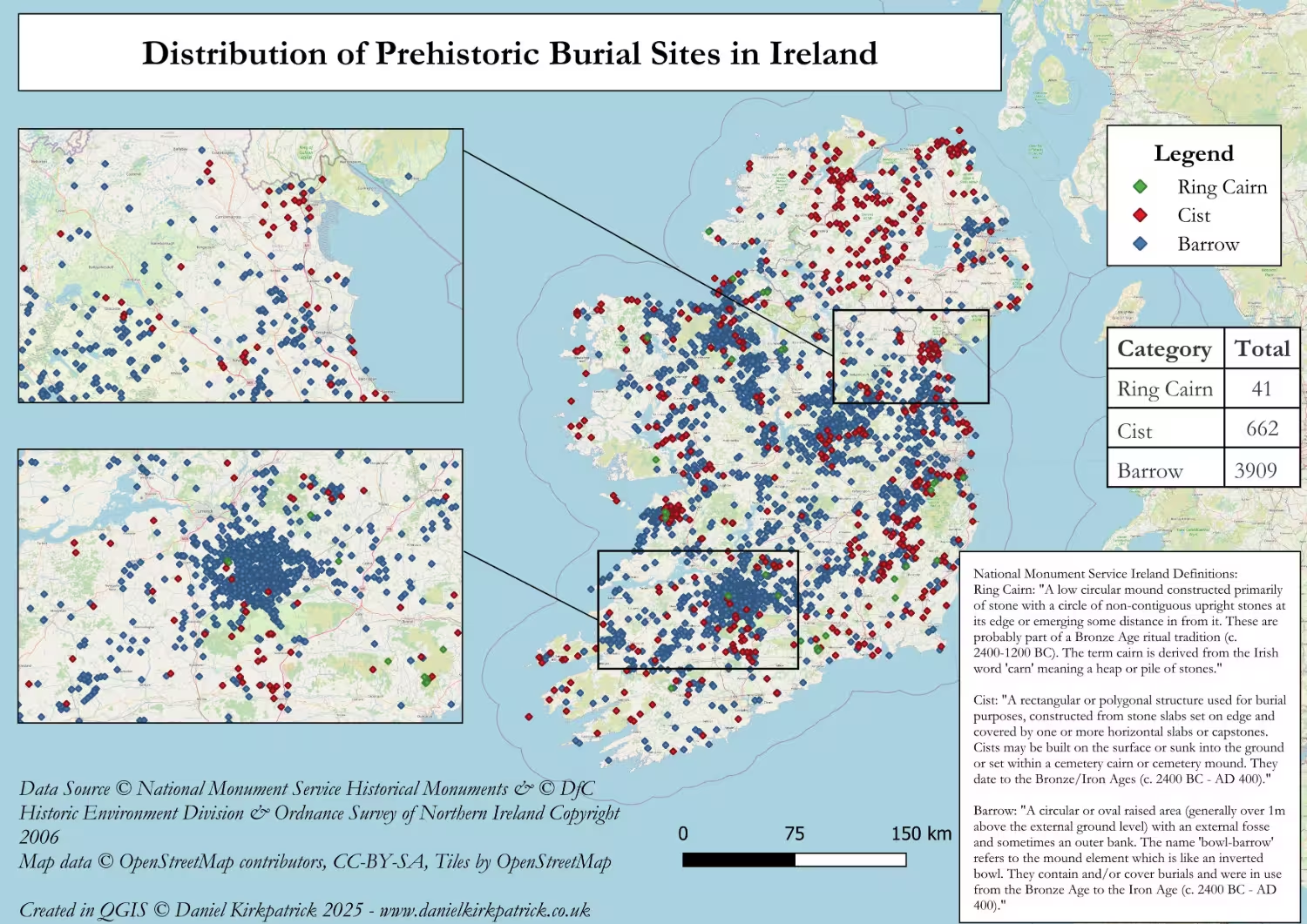

The name Aos Sí [pronounced ‘ees shee’] comes from the Old Irish Aes Sídhe, meaning “people of the mounds.” The word sídhe (modern Irish sí) refers to the ancient earthen mounds that dot the Irish landscape — passage tombs, barrows, and ringforts — many of which date back to the Neolithic and Bronze Ages. And from at least medieval traditions – likely much earlier too – these mounds were believed to be portals to the otherworld, the so-called realm of the Aos Sí. For it was into these mounds that the ancient gods were believed to have retreated.

However, over time the term evolved into something much looser and removed. In English, sídhe was often rendered as “fairy,” though this translation risks oversimplifying their complex role. In fact, fairies are essentially a folkloric taxonomy for a subset of mythical creatures, like cats refers to lions and leopards. And unlike the short-gnomelike fairies of later European folklore, the Aos Sí were depicted as tall, noble, and formidable beings – more akin to more modern depictions of elves. Indeed, there’s been much speculation about whether they were the source of inspiration for Tolkien’s elves – though that’s a whole post in and of itself. Instead, we shall turn to what we do know – the origins of the Aos Sí in Irish mythology.

Aos Sí Origins in Mythology

The Aos Sí are most often connected with the Tuatha Dé Danann, the divine race of Irish mythology. According to the Lebor Gabála Érenn (Book of Invasions), the Tuatha Dé Danann were defeated by the Milesians, the mortal ancestors of the Irish. But rather than being destroyed, the Tuatha were forced to retreat underground, taking residence in the great burial mounds and hollow hills scattered across the landscape. From there, they became the Aos Sí — the hidden people who continued to influence the world above.

This myth offers a fascinating explanation for Ireland’s ancient monuments showing us one possible view from at least the 8th century – likely much earlier. Sites like Brú na Bóinne (Newgrange), Knowth, and Dowth, which would have been shrouded even then in mystery, became associated with gods who moved beneath the earth. Local folklore extended this to smaller features too — ringforts, liosanna, and even lone bushes in fields were seen as entrances to their world. To damage or disturb such places was to risk the wrath of these ancient beings.

Yet the Aos Sí were not always seen as malevolent. In early stories they appear as hosts of noble, otherworldly figures — beautiful, powerful, and sometimes willing to aid mortals. The god Aengus, for instance, was believed to reside at Newgrange, while the Dagda was said to rule from there (before being tricked by his son Aengus). Over time, and as Christianity reshaped Ireland’s culture, the Aos Sí shifted into more ambiguous spirits. They became neither fully divine nor fully mortal, but beings whose respect was to be carefully maintained.

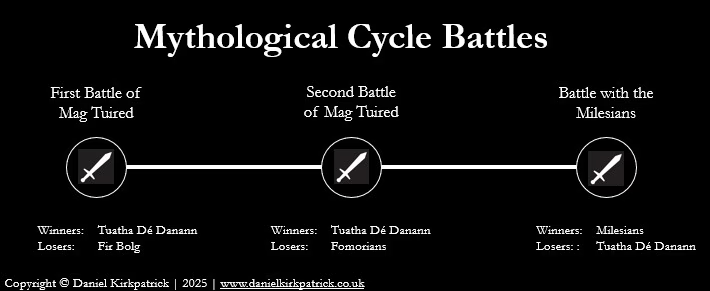

The Second Battle of Moytura

One of the most significant mythological accounts involving the Aos Sí is found in the Cath Maige Tuired (The Second Battle of Moytura). This epic narrative details the conflict between the Tuatha Dé Danann and the Fomorians, a race of supernatural beings. The Aos Sí are often associated with the Tuatha Dé Danann, and their involvement in this battle underscores their role as powerful and influential entities within the mythological hierarchy.

In the battle the Tuatha Dé Danann are led by their king Nuada against the Fomorians. They engage in various acts of valor and strategy, employing magical arts and supernatural abilities to combat the Fomorians. After their victory, the goddess Morrigan announces their victory notably to the Aos Sí:

“Then after the battle was won and the slaughter had been cleaned away, the Morrígan, the daughter of Ernmas, proceeded to announce the battle and the great victory which had occurred there to the royal heights of Ireland and to its síd-hosts, to its chief waters and to its rivermouths.”1

Following their victory, the Tuatha de Danann settle as the victors. But their victory is soon curtailed with the so-called arrival and conquest of the Milesians.

Defeat of the Tuatha Dé Danann

In the final episode of the Mythological Cycle, the Tuatha Dé Danann faced their greatest challenge — the arrival of the Milesians, descendants of Míl Espáine, whose people had journeyed from Iberia. According to the Lebor Gabála Érenn (Book of Invasions), the Milesians came to Ireland in fulfilment of a prophecy that foretold their dominion over the island. When they landed, conflict quickly arose between them and the Tuatha Dé, who had ruled since their victory at Mag Tuired.

The Milesians were skilled in war and magic, and the Tuatha sought to outwit them with their own supernatural arts. The goddess Ériu, one of the sovereignty figures of Ireland, welcomed the newcomers and promised them the land if they honoured her. Her sisters Banba and Fódla did the same, and the island came to bear Ériu’s name: Éire (Ireland). Yet not all encounters were peaceful.

The Milesians were challenged to take their ships “nine waves out” before attempting to return, a magical test imposed by the Tuatha. As they sailed back, storms were raised against them by the Tuatha’s druids, but the Milesian poet Amergin calmed the seas with an invocation to Ireland itself.

When battle followed, the Milesians prevailed. Their victory marked the end of the Tuatha Dé Danann’s rule in Ireland. Defeated but not destroyed, the Tuatha withdrew into the great burial mounds and hollow hills, thereby becoming the Aos Sí — the “people of the mounds.” From that point, they lived on not as gods but as the hidden fairy host, shaping Ireland’s otherworldly folklore for centuries to come.

Seasonal Associations and Rituals

The Aos Sí are also closely linked to specific times of the year, particularly during seasonal transitions and festivals. Samhain, marking the end of the harvest and the beginning of winter, was a time when the veil between the worlds was believed to be at its thinnest. Folklore said this allowed for increased interaction between humans and the Aos Sí. Therefore, during this period it was customary to offer sacrifices and perform rituals to appease the Aos Sí thereby ensuring protection through the coming winter months.

Similarly, Beltane – celebrating the arrival of summer – is associated with the Aos Sí through fire festivals and fertility rites. These seasonal observances highlight the Aos Sí’s integral role in the cyclical nature of life and death, growth and decay, within the Irish cultural and spiritual landscape.

Comparisons and Parallels

While the Aos Sí are distinctly Irish in character, similar beings appear across Celtic tradition.

In Scotland, the Sìth share both the name and the association with hills and mounds, while in the Isle of Man, tales of the Mooinjer Veggey (“little people”) echo the same themes of hidden folk who demand respect from mortals. These shared traditions suggest a common Celtic belief in spirits of the landscape who guard liminal spaces.

Beyond the Celtic world, parallels can be drawn with other European traditions. Roman writers described local gods and spirits tied to natural features such as rivers and groves, while in Norse mythology the álfar (elves) played a similar role as otherworldly beings living alongside humans.

What sets the Aos Sí apart, however, is their strong connection to Ireland’s prehistoric monuments. The mounds and ringforts that dot the Irish countryside gave the fairies a physical presence in the land itself, rooting them in a way that many other traditions lack.

The contrast with later Victorian ideas of fairies is also striking. In the nineteenth century, fairies were often softened into miniature, whimsical beings with delicate wings, far removed from the powerful Aos Sí of Irish belief. This transformation reflects the shift from a living tradition bound to the landscape into a romanticised vision shaped by art, literature, and children’s tales.

Comparison between Aos Sí and other Mythological Creatures

| Culture | Mythical Beings | Nature / Role | Dwelling Places |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irish (Celtic) | Aos Sí | Supernatural race, descendants of Tuatha Dé Danann; guardians of nature and liminal spaces | Fairy mounds (sídhe), barrows, lakes, forests |

| Scottish (Celtic) | Sìth / Daoine Sìth | Similar to Aos Sí; sometimes equated with fairies or spirits of the dead | Mounds (sìthean), hills, remote landscapes |

| Welsh (Celtic) | Tylwyth Teg | Fair folk; beautiful, otherworldly beings with links to abduction and time distortion | Underground or lakes |

| Norse | Álfar (Elves) | Supernatural beings tied to fertility, prosperity, and the natural world | Álfheimr (Elf-home), burial mounds |

| English / Anglo-Saxon | Fair Folk / Fae | Trickster-like fairies, often capricious and tied to folk belief | Woods, hills, fairy rings |

| Classical (Greek) | Nymphs | Female nature spirits linked to rivers, trees, and groves | Natural sites (springs, woods, mountains) |

| Slavic | Vila / Rusalka | Enchanting female spirits; sometimes benevolent, sometimes dangerous | Forests, lakes, rivers |

Legacy and Modern Influence

By the nineteenth century, writers and folklorists such as Lady Gregory, W. B. Yeats, and Douglas Hyde recorded living traditions of the Aos Sí. In their collections, fairies were still spoken of with caution and respect, especially in rural communities where fairy forts and mounds remained sacred. Even in recent decades, roads have been diverted to avoid cutting through fairy paths, showing how persistent these beliefs remain.

In modern culture, the Aos Sí continue to influence literature, art, and film. They appear in fantasy fiction and role-playing games, often as otherworldly beings both beautiful and dangerous. Yet this contemporary image often simplifies or romanticises them, overlooking the complexity of the traditions that portray them as guardians of Ireland’s sacred places.

Despite these changes, the Aos Sí endure as one of the most recognisable and powerful elements of Irish mythology, a living reminder of how the landscape and the supernatural remain entwined.

For readers interested in exploring related traditions, the Aos Sí can be seen alongside other mythological beings such as the cailleach or the merrow — each reflecting a different aspect of Ireland’s supernatural imagination.

Frequently Asked Questions: Aos Sí

The Aos Sí are the supernatural fairy folk of Irish mythology. Often called the “people of the mounds,” they inhabit ancient burial mounds, ringforts, and other sacred sites. They are closely linked to the Tuatha Dé Danann and appear in numerous myths and folktales as both guardians and tricksters.

The term Aos Sí literally translates to “people of the mounds.” The word sí (or sídhe in older texts) refers to earthen hills or burial mounds believed to be entrances to the Otherworld.

Yes and no. While the Aos Sí are often referred to as fairies, they are much older and more powerful than the diminutive, whimsical fairies of Victorian folklore. They represent supernatural forces tied to the land and Irish mythological history.

The Aos Sí are believed to dwell in raths, barrows, and other ancient mounds, often located in rural or sacred landscapes. These places were treated with caution, as disturbing them was thought to bring misfortune.

Key stories include encounters with humans who trespass on fairy mounds, and their association with the Tuatha Dé Danann, such as in the Second Battle of Moytura. Folklore also links them to festivals like Samhain and Beltane.