The Fomorians (Fomóire) are among the most mysterious and fearsome beings in Irish mythology. Often described as monstrous, deformed, or giant-like, they represent the destructive and chaotic forces of nature — the darkness that opposes order and civilisation. However, they are far more than simple villains.

The Fomorians embody primal powers connected to the sea, storms, and death. With gods like Lugh being a descendant of the Fomorians, and others intermarrying (which would have indicated ancient alliances), their relationship was far from mere enemies. Whether as raiders from across the waters, or as an ancient Mesolithic race of Ireland, their legacy is complex. To explore the stories of the Fomorians is to uncover Ireland’s oldest myths about creation, conflict, and the balance of power between destructive and creative forces.

In this post we will consider the etymology, primary sources, and chronology of this legendary people group. Whether they are truly the mythological creatures they’re often portrayed as today, I will leave that judgement to you.

Etymology of Fomorians

The very name Fomóire (singular Fomóir) has long fascinated scholars and storytellers alike. Its meaning is uncertain, and medieval commentators offered multiple accounts, each coloured by the way these beings were imagined in story and tradition.

From a linguistic perspective, the debate centres on the second element of the word. One widespread interpretation sees fo- (“under, below”) combined with muir (“sea”), giving “those from under the sea.” This matches the narrative depiction of the Fomóire as sea-borne raiders, arriving from overseas to oppress Ireland. Yet this is not the only possibility. Some philologists argue that the second element is not muir but instead related to mor (“great”) or mare (“phantom, spirit”). If so, the term might mean “great under-ones” or “phantoms from below,” evoking a more otherworldly character. This aligns with the belief that they were the ancient Irish cthonic beings, both dwellers of Ireland and of the otherworld.

To see these narratives played out, we need to turn next to the mythological record.

Mythology of the Fomorians

The earliest accounts of Ireland stem from four narrative cycles, the first being the mythological cycle. The other three are the Ulster Cycle, Fenian Cycle, and the Historical Cycle, each charting later periods of prehistory. These are – at most – pseudo-historical accounts written down by monks in the early medieval period, blending mythology with historical narrative.

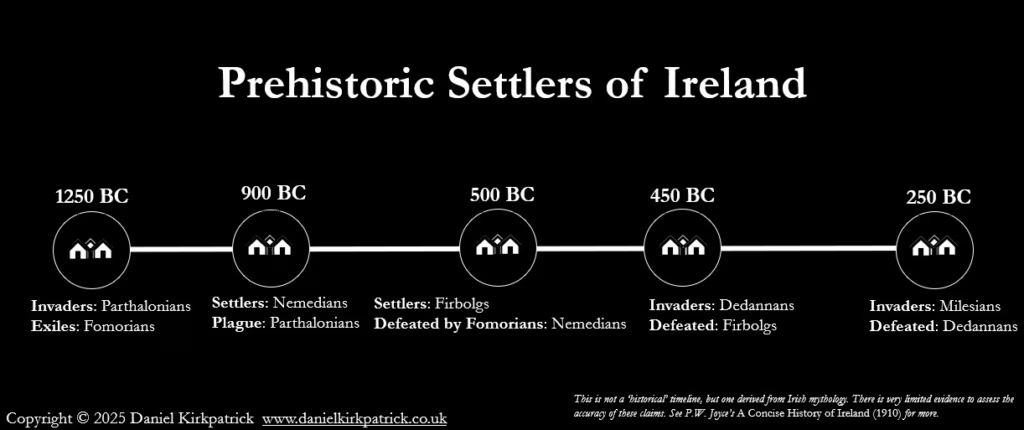

Within the Mythological Cycle, the Fomorians act as key figures across a series of battles and invasions. But their role is far from binary and it’s worth charting the chronology itself, as it contextualises the various ways they are represented.

Defeat by Partholón

Their story begins with defeat. According to Lebor Gabála Érenn, or The Book of the Taking of Ireland, the Fomorians were one of the earliest peoples to have settled Ireland. But in the late Bronze Age, a mythological people group led by a figure named Partholón invades. Partholón and his people battle the Fomorians, who are led by Cichol Gricenchos, at the Battle of Mag Itha.

Retreating into exile, the Fomorians are said to have fled to the Hebrides and the Isle of Man.1 Some have pointed to this relating to them being later regarded as sea-raiders, or sea dwellers, despite being the earlier inhabitants of Ireland. However, others gloss over this account entirely and describe their arrival as coming later (after the Nemedians) as “pirates from Africa”.2

But fate has her way and the Parthalonians later die of the plague leaving Ireland once again open to the Fomorians. Only this time, another group have settled – the Nemedians.

Oppression of the Nemedians

The Nemedians are said to have settled Ireland sometime around 900BC having come from Sythia. However, they soon become victims to Fomorians raiders who place impose punitive tribute upon them. Demands for grain, cattle and slaves, drive the Nemedians to eventually strike back and rise up against their oppressors.

One of the earliest conflicts describes how the Nemedians fought the Fomorians near Tory island, an island fortress said to lie off the coast. Though the Nemedians achieved a partial victory, they suffered devastating losses, leaving only a small remnant of survivors. This story established the Fomorians as both conquerors and destroyers, capable of crushing entire peoples from their sea-based strongholds. Today Tory island remains remembered for this mythical battle, located just north-west coast of County Donegal.

But the real fighting hadn’t yet truly begun.

The First Battle of Mag Tuired

The next chapters in the Mythological Cycle portray a more complex picture of the Fomorians. At this stage in the narrative, the Fir Bolg settle dividing Ireland into five kingdoms between their leaders. But it’s not long before another race invades and war ensues.

The Dedannan are the next to invade Ireland and eventually culminating in two great battles. In the first of these, known now as the First Battle of Mag Tuired, the Tuatha Dé Danann fight and defeat the Fir Bolg. In this conflict, the Fomorians remain in the background and appear to play both sides. First they form an alliance with the invading Tuatha Dé Danann. marrying one of their great leaders to the daughter of the King of the Fomorians:

“The Túatha Dé then made an alliance with the Fomoire, and Balor the grandson of Nét gave his daughter Ethne to Cían the son of Dían Cécht. And she bore the glorious child, Lug.”

The result of this union was none other than the god Lugh (known here has Lug), but we’ll return to this point later. On the other side, after the conflict concludes the Fir Bolg then retreat to the lands of the Fomorians.

“Then those of the Fir Bolg who escaped from the battle fled to the Fomoire, and they settled in Arran and in Islay and in Man and in Rathlin.”

It’s not until later that we see the Fomorians reveal their true nature, once the weakened forces of the Tuatha Dé Danann have secured victory. Having clearly learned nothing from their devastating encounter with the Nemedians, the Fomorians once more impose an oppressive tribute upon the inhabitants of Ireland.

The Second Battle of Mag Tuired

In the first Battle of Mag Tuired, the king of the Dedannan’s – Nuada – is severely maimed, losing his hand. His right to rule is thus called into question and the Fomorians seize upon the opportunity to enthrone one whose parents are a mix of the two races: Ériu of the Dedannan’s and Elatha of the Fomorians. Their child, Bres, is enthroned in place of Nuada and so begins the trouble of the Tuatha Dé Danann anew.

“But after Bres had assumed the sovereignty, three Fomorian kings (Indech mac Dé Domnann, Elatha mac Delbaith, and Tethra) imposed their tribute upon Ireland—and there was not a smoke from a house in Ireland which was not under their tribute.”

Bres’ rule is disastrous, impoverishing the people and himself. Eventually he falls victim to a satire and his authority begins to unravel. His maternal kinsmen seek him to stand aside. Bres pretends to agree, only to then call aid from his paternal allies in the Fomorians.

The war which follows is a fascinating narrative itself and far longer than this post can cover here. But for our purposes here, the war reaches its climax at the Second Battle of Mag Tuired. Victory is only secured once Balor, King of the Fomorians, is slain by his grandson Lugh – I said we’d return to him. In this way, the Fomorians are both the villains and heroes. This isn’t a simple good versus evil narrative, but reflects the complex intermingling of peoples on both sides – a fact often missed throughout much of Irish history.

End of the Fomorians

The mythology of the Fomorians ends with a simple declarative statement that: “Immediately afterwards the battle broke, and the Fomoire were driven to the sea.” In other words, they went back to where they’d come from never to return. But this isn’t the whole truth for their legacy remained and intermarriage had ensured their children would continue to inhabit key leadership roles thereafter.

For me, this narrative reflects themes which would have undoubtedly been in the minds of the original listeners. Ireland was a land beset by raiders, whether from Scotland, Wales, or further afield again. Indeed, if this was truly a medieval creation, the invasions of the Vikings or Normans would have likely been in the mind of the authors. In this sense it was a fantastic piece of propaganda.

Legacy and Significance

The Fomorians stand as one of the most striking forces in Irish mythology. They are more than villains in a mythic tale; they embody the destructive powers of nature, the chaos of the sea, and the dangers of tyranny. Through stories of Balor, Lugh, and the battles for Ireland, the Fomorians represent the eternal struggle between disorder and civilisation.

Their myth reflects the fears and realities of early Irish life, when storms, invasions, and famine could undo communities overnight. Yet it also carries a hopeful message: order and renewal can overcome destruction, just as Lugh triumphed over Balor.

Even today, the Fomorians remain powerful symbols. They connect Ireland’s mythic past to wider traditions of cosmic conflict found across Europe, while continuing to inspire literature and fantasy. To explore the Fomorians is to glimpse how the Irish once understood the balance between chaos and order — a theme that is as relevant now as it was in the time of the mythology.

Frequently Asked Questions: Fomorians

The Fomorians were a race of supernatural beings, often later depicted as monstrous or deformed, representing chaos and destruction in early Irish myths.

Derived from Old Irish Fomóire (Modern Irish Fomhóraigh), the name’s exact meaning is debated. Common interpretations include “undersea beings,” “great under-ones,” or “underworld demons,” reflecting their otherworldly and fearsome nature.

They frequently clashed with the Tuatha Dé Danann in the Mythological Cycle, particularly during the Battles of Mag Tuired, symbolising the struggle between chaos and order.

Not entirely. While they are often antagonists, some traditions portray them as rulers, kings, or ancestors, embodying both destructive and primordial forces.

They were said to originate from across the sea or from beneath the earth, representing forces beyond human control or understanding.

- Celtic Mythology. Geddes & Grosset. Scotland, 1999. p376. ↩︎

- While none of this likely has any historical bearing, this reading appears potentially even racist in its connotations particularly given the time it was written. https://www.libraryireland.com/WestCorkHistory/FirstInhabitants.php ↩︎