Last Updated: 22nd July 2025

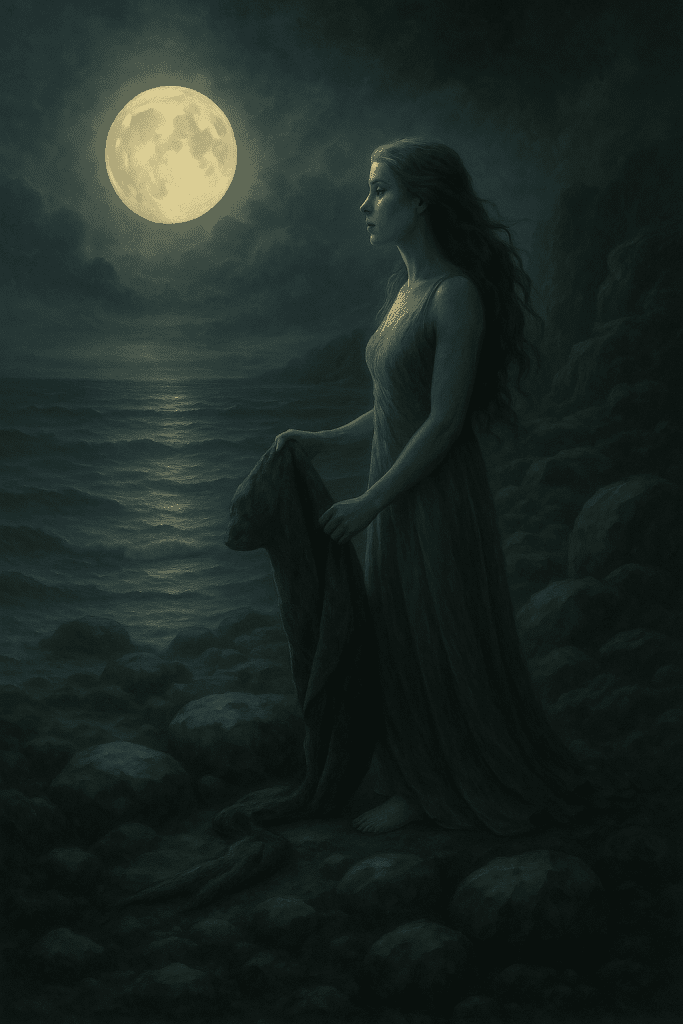

The boundaries between death and life, love and tragedy, hope and despair, are often far more permeable than we image. And in Irish mythology, these boundaries are central to the narratives which have been passed down through centuries of storytelling. And no more so, than for the Selkies: creatures carrying the souls of drowned sailors; shedding their animal skin to become human and live on land; forced to choose between lives of captivity with their children or escape alone to the sea. The Selkies – living between land and sea – pass between life and death. Their love for life exists in tension with the life they love. They are the embodiment of much we struggle to express.

It’s no wonder, then, that the Selkies have inspired generations of folktales spanning multiple cultures and beliefs. This post considers who they were and the stories that surround them. It discusses their significance and symbolism, their Celtic roots, comparisons with wider mythological traditions, and archaeological evidence. Hopefully they will inspire you as they have done countless generations before, as symbols of the paradoxes of life.

This links to other Irish mythical creatures I’ve covered including the Cailleach and the Merrow.

Irish Selkie Folklore

The word selkie derives from the Scots term selchie/silkie, literally “seal” – a usage recorded in Orkney and Shetland dialect glossaries of the mid-1800s. Irish storytellers often call the same beings maighdean mhara (“sea-maid”) or, in Ulster Scots pockets of Donegal, simply “seal-woman”. While Orkney ballads situate the dramas on islets like Sule Skerry, collectors in Galway and Clare repeat virtually identical plots, underscoring the motif’s migration along the North Atlantic region.1

At the heart lies the “stolen skin” tale. A fisherman surprises seals dancing in human form under the moon, snatches one skin and refuses to return it unless the woman becomes his wife; she bears children but eventually recovers the hidden pelt and escapes, sometimes leaving a sorrowful message etched on a sea-rock.2 Variants reverse the genders or add tragic elements – for instance, in the Child-ballad “The Grey Selkie of Sule Skerry”, the seal-father prophesies his own harpooning by the woman’s future husband.3 In Ireland, the descendants of silkes were said to be prohibited then from hunting seals. But to understand the selkies, we must understand how these communities viewed seals themselves.

Table: Primary Selkie Myths and Folklore

| Region / Culture | Story / Legend | One-Sentence Synopsis | Core Motifs | Principal Sources & Collectors* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orkney (Scotland) | “The Goodman o’ Wastness” | A farmer hides a selkie woman’s sealskin; she bears him seven children but escapes the moment she finds it. | Stolen skin, captive bride, children of two worlds | Walter Traill Dennison, Orcadian Sketch-Book (1880) |

| Shetland (Scotland) | “The Great Selkie of Sule Skerry” (ballad) | A selkie fathers a child with a crofter’s daughter; years later he reclaims the boy before both perish at sea. | Shape-shifting lover, foretold tragedy, sea-claim | Child Ballad 113; Francis James Child, The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (1882–98) |

| North Uist (Outer Hebrides) | MacCodrum Selkie Wife | Clan ancestor Donald MacCodrum marries a seal-woman; her hidden skin is found by their son, freeing her to return to the sea. | Founding lineage, inherited “seal blood”, skin concealment | Alexander Carmichael, Carmina Gadelica (1900); local oral tradition |

| Faroe Islands | “Kópakonan” (Seal-Woman of Mikladalur) | Fishermen steal skins from dancing selkies; the captured bride vows revenge, later causing many drownings after regaining her pelt. | Revenge oath, drowned fishermen, coastal warning | Jakob Jakobsen, Færøske Folkesagn og Æventyr (1898); statue in Mikladalur (2014) |

| Ireland (Donegal) | “The Seal-Hunter and His Selkie Bride” | A hunter weds a selkie girl; when he breaks a taboo and kills a seal, she disappears, leaving their half-selkie children. | Taboo breach, animal kinship, loss & lament | Seán Ó hEochaidh field recordings, Irish Folklore Commission (1930s) |

| Iceland | “Selshamurinn” (The Seal-Skin) | A farmer coerces a seal-maiden into marriage; after years she finds her skin and vanishes, but later saves their sons from drowning. | Coerced marriage, maternal return, protective magic | Jón Árnason, Íslenzkar Þjóðsögur og Æfintýri (1862–64) |

Selkies in Celtic Mythology

The relationship between seals and sea communities has always been complex. With some revering them, such as parts of the Hebrides where seals were believed to carry the souls of drowned fishermen.4 Other Irish traditions hold that seals were the drowned children of the giant Balor, the mighty king of the Fomorians.5 As the mythological tradition explains, these were the people group who populated Ireland before the Tuatha de Dannan arrived. It was through a series of battles that they were defeated, but it seems some believed that defeated warriors lived on through seals.

Even St Patrick was said to have said Mass while standing on a seal skin, which was then attributed with many miracles. In another Christian legend, St Mochua was refreshed by four salmon which a seal brought to him.6 Regardless of their accuracy, such legends show the sacredness of seals and superstitions that would have surrounded them.

Their spiritual significance was likely interlinked to their value and role in the lives of early coastal communities. Seals were both as a source of many key resources (meat, hide, bone, oil) as well as a competitor competing for fish stocks.7 Mesolithic middens on Orkney contain juvenile seal bones deposited alongside human hand bones, suggesting symbolic as well as subsistence value. While no artefact “proves” selkie belief, the archaeological record illustrates an ancient intimacy with seals that could fertilise myth.

Did you know?

In some Irish coastal communities, it was once believed that seals were the souls of drowned fishermen—killing one could bring misfortune to an entire village.

Selkie Comparative Mythology

The Selkie myth broadly falls under the “The Swan-Maiden” class: a supernatural woman whose skin or feather cloak is stolen to secure marriage. In such plots, the key framing is possession of the transformative garment; the difference is zoological, not structural. That consistency suggests a very old narrative spine that coastal regions likely coopted as their own.

Irish selkies share the sea with Norse fin-folk, amphibious sorcerers who likewise kidnap human spouses but crave silver rather than skins. Mermaid lore parallels the desire/loss cycle yet lacks the shedding of skin, signalling a shift from shape-shifting to hybrid anatomy (much like the centaur or other human/animal combinations). The comparison underlines how each culture negotiates maritime danger: seals are familiar, fin-folk uncanny, mermaids seductive but fatal.

Inuit mythology has Sedna/Nuliajuk, the sea-mother who controls seals and whose fingers—severed by her father—become marine mammals. Instead of a stolen skin we meet a cosmic origin myth, yet both traditions treat seals as boundary-markers between human survival and the unknowable deep. The likeness strengthens the view that subsistence economies – like those of coastal ancient Ireland – shape narrative tropes around the animals that feed them.

Selkies and Archaeology

Mesolithic and early Neolithic middens on Oronsay, Shetland and Orkney consistently mix seal and human remains, hinting at ritual as well as diet. The Shetland West Voe’s layered oyster- and limpet-shell dumps, dated c. 4800–3500 BC, yielded repeated clusters of seal and seabird bones. Zoo-osteological work on Baltic Pitted Ware sites shows similar patterned deposition and selective handling of skulls, reinforcing the idea that seals carried symbolic weight across northern hunter-gatherer societies.

A 2,000-year-old seal-tooth pendant from the Knowe of Swandro, Orkney, joins caches of buried seal teeth at Iron-Age Loch na Beirgh and flipper-hand double burials on Oronsay. Late Neolithic bone industries at Skara Brae and Links of Noltland include worked seal bones alongside whale and deer, demonstrating technological as well as mythic integration of marine mammals.

Despite this, no artefact inscribed “selkie” has surfaced, and direct continuity from midden to myth remains untestable. What the bones do show is a sustained, intimate entanglement between people and seals: ecological dependence plus anatomical resemblance (seal flipper bones famously mimic human phalanges) offers fertile ground for shapeshifter tales. Material and folklore thus intersect, but neither conclusively verifies the other.

Selkies in Contemporary Culture

Selkie mythology has surged back into the mainstream during the last three decades, giving digital-age audiences fresh ways to meet Ireland’s shapeshifting “seal folk”. From award-winning screen adaptations – Song of the Sea (2014) or The Secret of Roan Inish (1994) – to contemporary literature & graphic storytelling – for instance Sealskin by Su Bristow – bring these ancient mythological creatures to modern audiences.

Tourism has taken full advantage of the stories with selkie-themed kayak tours in Orkney and storytelling walks on the Wild Atlantic Way. Even within the academic world, EU researchers borrowed the name for the SELKIE Project, an R&D initiative on wave-energy toolkits that markets tidal innovation under a folkloric banner.

The creature’s enduring appeal shows that it remains a compelling symbol. Despite its rather sinister undertones and roots, it illustrates the complex relationship between humanity and the land we live in. At a time when we are so disconnected from the food which sustains us, such myths speak to a lost intimacy – or at least acknowledgement – between ourselves and the ecology we depend upon. If nothing else, that is certainly worth remembering.

Frequently Asked Questions: Irish Selkie Folklore and Mythology

What is a selkie?

A selkie is a mythical creature found in Irish, Scottish, and Faroese folklore, believed to be a seal that can shed its skin and become human on land. These beings often feature in tales of love, loss, and transformation.

Are selkies part of Irish folklore or just Scottish?

While selkie legends are most commonly associated with Orkney and Shetland, Ireland has its own rich tradition of seal-folk, particularly along the western and northern coasts, where seals were revered and feared as shape-shifters with magical ties to the sea.

What is the difference between a selkie and a mermaid?

Selkies are seals who turn into humans by shedding their skins, whereas mermaids are typically depicted as half-human, half-fish beings. Selkie stories often focus on emotional bonds, lost identity, and longing, while mermaid tales lean more toward enchantment and danger.

What themes appear in selkie myths?

Key themes include transformation, exile, tragic love, and the tension between freedom and captivity. These stories often explore what it means to belong—to the land or to the sea.

Did Irish people really believe in selkies?

Yes—folkloric belief in seal-people was widespread in coastal communities, especially in areas where seals were common. Some even believed seals were the souls of drowned humans or fallen angels.

- Darwin, Gregory R. 2019. Mar Gur Dream Sí Iad Atá Ag Mairiúint Fén Bhfarraige: ML 4080

the Seal Woman in Its Irish and International Context. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard

University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences ↩︎ - https://www.historicmysteries.com/myths-legends/selkie/28219/ ↩︎

- Mcentire, N. C. 2010.’ Supernatural Beings in the Far North: Folklore, Folk Belief, and The Selkie‘. Scottish Studies 35, pp. 120-143. https://open.journals.ed.ac.uk/ScottishStudies/article/download/51/49/82 ↩︎

- Jon, Allan. (1998). Dugongs and Mermaids, Selkies and Seals. Australian Folklore: A Yearly Journal of Folklore Studies. 13. 94-98. ↩︎

- Niall Mac Coitir (2008) Ireland’s Animals: Myths, Legends and Folklore. The Collins Press., p199. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Darwin, p81. ↩︎