Art today is something we all take for granted. It’s ubiquitous presence makes it easy to forget what it truly represents, particularly when we look back at art throughout history. This is especially true when we look at the ancient forms of art from Ireland’s Neolithic past (4000-2500BC). For during this period – these so-called primitive societies – created artforms and styles which modern Irish art is deeply indebted towards. And yet, the absence of written records or historical accounts means we know so little about it. But this makes what we do know all the more fascinating. I’m not talking of the many colourful conspiracy theories that fill our social feeds, but the archaeological evidence we are only beginning to truly unpack.

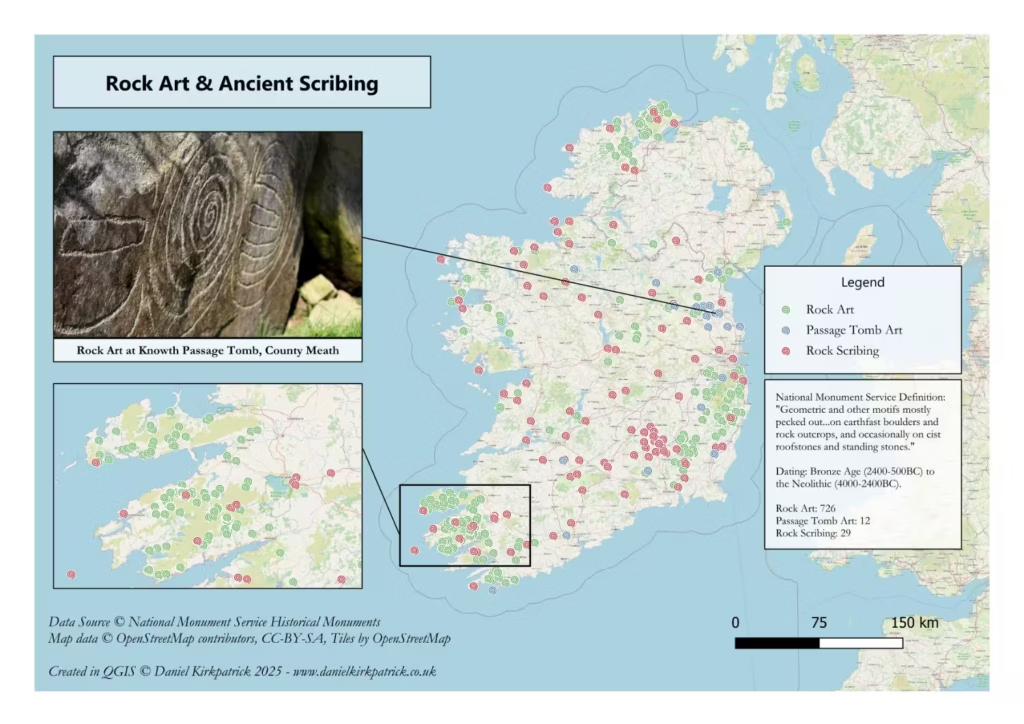

This post, therefore, explores the historical context of Neolithic art, providing an interactive map of all recorded locations for rock art and rock scribing across Ireland. We will set these artforms in context to understand what they relate to, how they were created, and what their possible significance may once have been.

Interactive Map of Rock Art and Scribing locations in Ireland

This interactive map was created in QGIS using data from the Department for Communities NI datasets. Copyright for the data and basemaps attribution is as follows:

Data Sources: © DfC Historic Environment Division & Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland Copyright 2006

Map data: © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC-BY-SA, Tiles by OpenStreetMap

You can see here for the full inventory of my maps.

Defining Rock Art

Defining “rock art” in an Irish context is not as straightforward as it sounds. Archaeologists use the term to describe any deliberate markings made on natural stone surfaces in prehistory, but the Irish evidence spans several artistic traditions, techniques, and levels of complexity.

The best-known category is passage tomb art, created by pecking or incising designs onto the structural stones of great tombs such as Newgrange, Knowth, and Loughcrew. These motifs—spirals, arcs, lozenges, zigzags, and nested triangles—are dense, deliberate, and often positioned to interact with movement or light. Although scholars still debate their meaning, many agree they reflect cosmological thinking, ritual performance, and communal identity.

A second category is Atlantic rock art, sometimes called “cup-and-ring art.” This is Ireland’s most widespread form. Typical motifs include simple cup-marks, concentric rings, radial grooves, and occasional rosette patterns. These carvings were usually pecked into glacial boulders or exposed outcrops, often in places with long views over valleys or natural routeways. Unlike passage tomb art, which is tightly tied to specific monuments, Atlantic rock art stands independently in the landscape.

More recently, archaeologists have recognised a third category of rock scribing. These are fine, incised lines—sometimes geometric, sometimes more fluid—that differ from the deeper pecked or ground motifs of traditional rock art. Rock scribing may represent a separate practice, possibly later in date, and often appears on stones that were not previously known to carry decoration. Some researchers suggest a Bronze Age or early medieval context for certain examples, though the dating remains open.

How did Neolithic communities create rock art?

Creating rock art in Neolithic Ireland was a slow, skilled, and often communal process. These carvings required planning, the right tools, and a deep familiarity with the behaviour of stone. Experimental archaeology has shown how even a single cup-mark can take more than an hour to peck out using replica tools, and the more elaborate motifs at sites would have demanded days of focused work.

The dominant technique for most open-air carvings was pecking. Craftspeople used hammerstones of hard, fine-grained rock—often quartz, flint, or dense sandstone—to chip away the surface of a boulder. The repeated tapping created a shallow hollow or groove with the distinctive granular texture visible on authentic Neolithic pieces. The rhythm mattered as too soft, and the mark failed to register; too hard, and the stone fractured unpredictably.

Much passage tomb art was created by incising or grooving. Long, sweeping curves—such as the famous triple spiral at Newgrange—were cut using antler or stone chisels, sometimes finished with rubbing or grinding to smooth the lines. The precision of these motifs implies careful pre-planning. Some archaeologists believe the designs were lightly sketched or marked out beforehand, the carver tracing a mental or physical guide before committing to the final cut.

The final method was scribing. This involved delicate, fine incisions found at a growing number of sites. These lines were made with sharper tools, perhaps flint blades or metal points in later periods. Because they sit so lightly on the surface, they can be difficult to identify without raking light or 3D photogrammetry. Their fragility has also made them harder to date securely, but their presence adds a new layer of complexity to Irish rock-marking traditions.

Key Sites in Ireland’s Neolithic Rock Art Tradition

Although carved panels occur across many Irish landscapes, a small group of sites shows the richest concentration of Neolithic rock art and offers the clearest sense of how communities used symbolic marks in both ceremonial and everyday settings. At Newgrange, the famous Entrance Stone carries some of the most technically accomplished spirals and curving motifs in Europe, and the passage stones continue the theme with chevrons, arcs, and sweeping lines carved with remarkable control.

Knowth adds the greatest variety with dozens of stones covered with spirals, cross-hatching, parallel lines, and unusual swirling motifs that appear nowhere else. The sheer quantity suggests the site was a long-term focal point for carving, with designs added or reworked over generations. Further north-west, the hilltops of Loughcrew preserve arcs, sunbursts and chevrons that catch shifting light inside the chambers at certain times of year. Whether this effect was intended or incidental remains debated, but the interaction between light and stone undoubtedly shaped how people experienced the carvings.

Beyond the large passage tombs, open-air carvings in the Derrynablaha–Coomkeen region of Kerry and Cork remind us that rock art was not restricted to monumental landscapes. These panels—mostly cup-marks and concentric rings—sit in pastoral uplands, suggesting that symbolic carving permeated everyday environments as well as major ceremonial centres. Together, these sites show a shared visual language across Neolithic Ireland, expressed through regional styles and evolving traditions.

Legacy of Neolithic Rock Art

Neolithic rock art remains one of the most evocative traces of Ireland’s earliest communities. Even though we cannot translate these motifs with certainty, they continue to shape how we understand the deep past. The sheer age of the carvings forces us to rethink the scale of Ireland’s prehistoric story: people were not only building monuments and clearing fields, but also creating a symbolic language that endured for millennia.

Modern archaeological research adds another layer of significance. High-resolution scanning, 3D modelling, and detailed landscape studies are revealing differences between regional carving styles and how these panels interacted with light, movement, and ritual activity. As new discoveries emerge—especially from lesser-known rural sites—our picture of Neolithic Ireland becomes more complex and more human. Rock art is no longer seen as decoration alone but as part of a broader cultural practice tied to place-making, memory, and social identity.

These carvings also hold cultural and emotional value for local communities. Many panels sit on farmland or hillsides where people have lived for generations. When visitors encounter them, often by chance, the effect can be quietly powerful: a sense of direct contact with people who stood on the same ground more than 5,000 years ago. In these ways, Irish rock art bridges the gap between archaeology and lived experience. It offers a rare glimpse into the minds of Ireland’s first settlers and continues to inspire curiosity, reflection, and a deeper connection with our landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions: Irish Rock Art

Carved symbols—mainly spirals, circles, and cup-marks—made by early farmers between 4000–2500 BC.

With stone tools using pecking and grinding. Designs were carved slowly by repeated strikes.

Major sites include Newgrange, Dowth, Loughcrew, and open-air panels in Kerry, Donegal, and Wicklow.

Their meaning is uncertain, but they likely held ritual or symbolic significance for Neolithic communities.