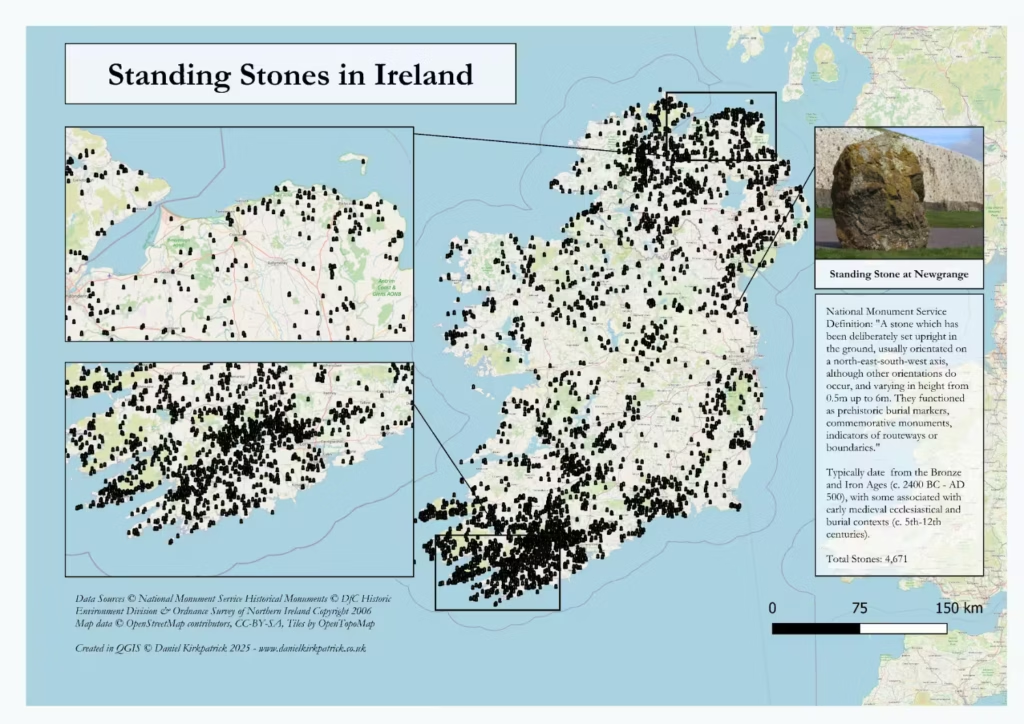

There are 4,671 recorded standing stones in Ireland, most dating back to the Bronze Age (2,500-500BC). That’s an incredible one standing stone every 7 square miles across the whole island. Most were originally established as memorial, ritual, or boundary markers, though there are likely many other uses we still don’t truly understand given the lack of historical evidence and our reliance on archaeology.

This post begins with an interactive map of all recorded locations for stone circles across the whole of Ireland. These include descriptions and details as provided by the respective Government sources used. For those interested in the wider background, we then consider what these stones were, why they were built, and some significant examples, before then qualifying this with the necessary data caveats. So read on if you’ve any interest in understanding more about these ubiquitous, yet mysterious, monuments which have marked Ireland’s landscape for 1000s of years.

Interactive Map of Standing Stones in Ireland

This interactive map was created in QGIS using data from both Government datasets. It includes all standing stone locations recorded by either government using filters for classification and description. Copyright for the data and basemaps attribution is as follows:

Data Sources © National Monument Service Historical Monuments © DfC Historic Environment Division & Ordnance Survey of Northern Ireland Copyright 2006

Map data © OpenStreetMap contributors, CC-BY-SA, Tiles by OpenStreetMap

What is a standing stone?

Standing stones referred to as menhirs in archaeological terminology. They are upright monoliths erected across the Irish landscape, most commonly during the Bronze Age (c. 2,500–500 BC). They vary greatly in size and shape, from slender, pointed pillars just a few feet tall to massive slabs reaching several metres in height. Many are solitary, while others form part of larger arrangements such as stone circles, alignments, or rows, often in conjunction with burial mounds or other ritual structures. Though when in a formation like this, they are typically classified separately (e.g. as stone circles).

Usually they are constructed from locally available stone though there are of course many exceptions – Newgrange is a good example of one discussed below. These monuments demonstrate remarkable skill in selection, transport, and erection of the materials. Some show evidence of deliberate shaping or polishing, while others retain their natural contours, suggesting that both symbolic and practical considerations influenced their design.

Archaeologists have noted that their placement is rarely random as stones are often positioned on elevated ground, along sightlines, or in alignment with natural features such as rivers, valleys, or distant hills. This careful siting hints at both practical and ceremonial intentions, making each stone a permanent marker of human activity and belief in the prehistoric landscape. Which brings to consider why they were built.

Why were standing stones built?

Most evidence suggests that these monuments were multifunctional, serving a combination of ritual, memorial, and practical roles within Bronze Age communities. Many stones appear to have marked boundaries, either of tribal territories, farmland, or sacred spaces, providing a permanent, visible marker in a landscape largely devoid of permanent constructions. In this way, standing stones acted as both social and geographical signposts, communicating ownership or significance across generations.

Ritual and ceremonial use is another prominent interpretation. Stones frequently appear in proximity to burial mounds, tombs, or ceremonial sites, suggesting a connection with ancestor veneration or spiritual practice. Some alignments and arrangements, particularly in stone circles or paired stones, may have been linked to seasonal events or astronomical phenomena, marking solstices, equinoxes, or lunar cycles. While we can only hypothesise about the exact rituals performed, the care taken in transporting and erecting these often massive stones implies that they held profound communal and symbolic importance.

Memorial functions are also evident in certain contexts. Individual standing stones may have commemorated prominent figures, events, or acts of devotion, although the lack of inscriptions in most cases leaves this open to interpretation. Beyond these commonly recognised purposes, some stones may have had practical or functional roles—serving as meeting points, waymarkers, or even territorial markers in legal and social disputes.

For me, however, I think it’s important to remember that these have existed across millennia, so it’s almost certain that their original purpose and function was changed over the centuries which passed them by. We can see this clearly if we consider but two of the most interesting examples.

Significant standing stones in Ireland

Among the thousands of standing stones across Ireland, a few sites stand out for their historical significance, scale, and enduring presence in folklore. Newgrange, in County Meath, is perhaps the most famous Bronze Age site in Ireland and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. While Newgrange is widely known for its massive passage tomb, its surrounding standing stones are also remarkable. Some of these monoliths are arranged in circles or alignments, often featuring subtle carvings such as spirals, lozenges, or cup marks.

These stones are thought to have played both ritual and astronomical roles, marking the rising sun at the winter solstice and creating a sacred landscape around the tomb. Their placement and artistic detailing reflect an extraordinary understanding of both the physical and symbolic landscape by the communities who erected them.

Then in Northern Ireland stands the aptly named Holestone in County Antrim. This solitary standing stone, sometimes referred to as the “wishing stone,” has been a focal point of local tradition for centuries. Folklore suggests that couples who clasp hands through the hole in the stone were guaranteed a long and happy marriage. While its origins date back to the Bronze Age, the Holestone demonstrates how standing stones could acquire layers of social and spiritual meaning long after their initial erection. Unlike Newgrange, which functions within a larger ceremonial complex, the Holestone illustrates the enduring significance of individual monoliths within local communities, serving both as a landmark and a cultural touchstone long after their original construction.

In these ways, standing stones remain very much part of Irish identity and culture. And with one nearly always within 10 miles of you wherever you are in Ireland, I find it an encouraging reminder.

Data Quality Considerations

While the interactive map and accompanying records provide a comprehensive overview of Ireland’s standing stones, it is important to recognise the limitations inherent in the data. The first challenge is data completeness, whereby the sources are often reliant on you and I reporting sites. While many of the obvious locations are therefore well mapped, it’s very likely at least some are missing from the data.

The second challenge is more fundamental – destruction. Across over 4,000 years of history it is certain that many of the sites have fallen victim to painful erosion of time. Seen as building materials, moved or destroyed as obstructions, or simply trampled by a passing bull – the list is almost endless. This is likely more prevalent in low-lying agricultural land, but it’s impossible to know the full extent of this.

And lastly, is me (and the various other humans populating this). We are likely to have made errors – hopefully small – in the research process. Whether recording, mapping, filtering, or anything else, human error will always remain a caveat we have to contend with.

Frequently Asked Questions: Standing Stones in Ireland

A standing stone, or menhir, is an upright prehistoric monolith, often Bronze Age (2,500–500 BC), used as a ritual, memorial, or boundary marker. Some feature carvings like spirals, cup marks, or geometric designs.

They marked territory, commemorated events or people, and served ceremonial or astronomical purposes, such as aligning with solstices or lunar cycles.

There are 4,671 recorded standing stones across Ireland, though the true number may be higher due to lost or undiscovered monuments.