Living in concrete jungles like we do, with so much built with little regard for its permanence or beauty, it’s difficult to fully appreciate the ancient Irish monuments dotted around us. Megaliths which have lasted over 6,000 years, built by a mysterious civilisation; it’s no wonder that we struggle to take it in when you stand in their shadowy midst. I recently visited several of these monuments with friends and secretly loved sharing my limited knowledge on their origins, purpose, and design. But it got me thinking that I should write a similar guide online, one which summarises the various types of Irish Megaliths, their functions, and what we do (and don’t) know about them. For they truly are incredible, especially those in Ireland.

Irish megalithic structures come in several distinctive types – from covered burial mounds to open stone rings – each with its own design and ritual purposes. By understanding their architectural features and archaeological contexts, we can distinguish, for example, a passage tomb from a court tomb or a henge from a stone circle. In Ireland, these include the various types of tombs: court, passage, portal, and wedge tombs. Then there are the other prehistoric monuments or features which include: cists, henges, souterrains, and stone circles. Many of these can be found together on the same site, but this post covers their respective features to help distinguish between them.

Court Tombs

Court tombs are among Ireland’s earliest types of Irish megaliths. They date to the early Neolithic (around 4000–3500 BC) and are largely confined to the northern half of Ireland. A court tomb typically consists of an open, stone-lined courtyard (the court) at one end of a long stone cairn. From this court a narrow passage leads into one or more interior burial chambers (a gallery) built of upright stone slabs (orthostats). The gallery is often divided into two or more chambers by jambs, and it may extend back beneath the cairn. In Creevykeel (Co. Sligo), for example, a pear‑shaped courtyard about 15 m long fronts a multi-chambered gallery inside a 55 m mound.

This design – an open “atrium” giving access to internal vaults – is the hallmark of court tombs. One can picture the court as an ancient outdoor enclosure (perhaps for ritual activity) like a temple courtyard, with the dead laid to rest in the inner chamber. Courts vary: some are oval or round, others are U‑shaped or trapezoidal. In a few rare cases a long cairn has courts and chambers at both ends. The overall shape of a court tomb is often trapezoidal, tapering from a broad court end toward a narrower rear. Hundreds of court tombs are known (over 320 in Ireland), but almost all lie in Ulster and adjacent counties. This pattern suggests they were built by a community concentrated in the northwest. Analogous long barrows are found in Neolithic Britain, reflecting a relatively shared European tradition.

Passage Tombs

Passage tombs (or passage graves) emerged after court tombs, in the mid-Neolithic. They are found not just in Ireland but across Atlantic Europe, from Brittany to Orkney. In its classic form a passage tomb has a large circular or oval mound (often up to 30–100 m across) with a stone kerb at the base, and a long narrow entrance passage leading to an inner chamber. The passage is usually quite low and narrow (so one walks bent over), while the central chamber is taller (sometimes corbelled into a beehive vault). The chamber may be round, oval or cruciform (with small side‐recesses), and often was intended for multiple burials. Roof stones or corbel vaulting securely cover the chambers.

In Ireland, the Boyne Valley tombs Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth are spectacular examples. For instance, Newgrange (c. 3200 BC) is a pear-shaped mound about 80 m across and 15 m high, surrounded by an inner ring of decorated stones. A 19 m passage runs deep into the mound to a cruciform chamber with a 6 m-high corbelled vault.

Passage tombs tend to be sited on high ground, ridges or prominent landscapes, often in cemeteries of many mounds. Unlike court tombs, which are localised in the northwest, passage graves are widespread. By some counts there are several hundred in Ireland (the three Boyne mounds alone would be hard to match elsewhere). Some smaller passage tombs have little or no roof and can be low polygonal chambers (sometimes resembling a flat-roofed dolmen). In all cases, the combination of a passageway leading into a closed chamber under a mound is the defining feature. In analogy, one might imagine each passage tomb as a “stone crypt” with an access corridor – a sophisticated communal mausoleum of its day.

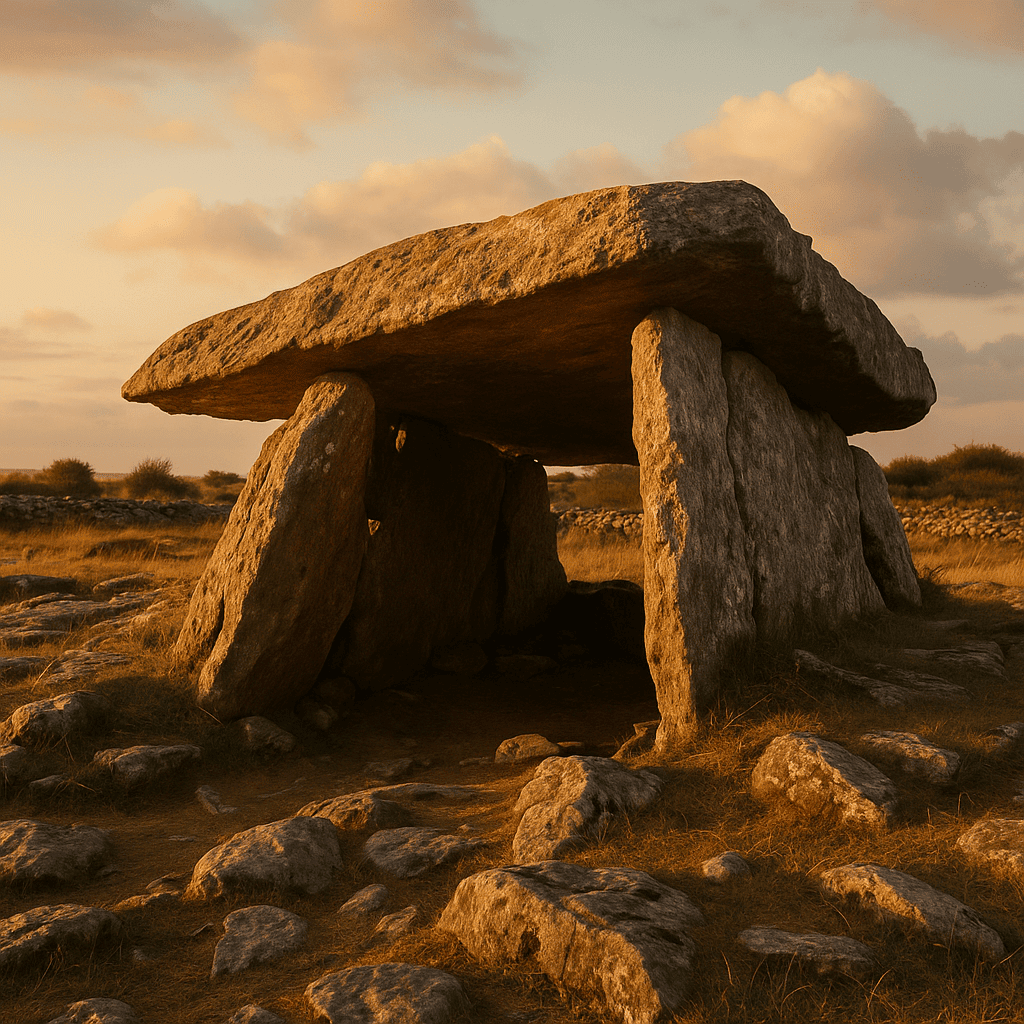

Portal Tombs (Dolmens)

Portal tombs, commonly referred to as dolmens, are among Ireland’s most iconic megalithic structures, dating from approximately 3800 to 3000 BC. These monuments typically consist of two or more large upright stones (portal stones) supporting a massive horizontal capstone, creating a chamber beneath. Originally, the chamber would have been covered with a cairn of smaller stones, which has often eroded away, leaving the striking stone skeleton visible today.

Portal tombs are predominantly found in lowland areas, often situated in valleys or near rivers. Notable examples include the Poulnabrone Dolmen in County Clare, set against the karst landscape of the Burren, and the Brownshill Dolmen in County Carlow, which boasts the largest capstone in Europe, estimated to weigh over 100 tonnes.

These tombs are believed to have served as communal burial sites, with excavations revealing human remains, pottery, and other artifacts. Their construction demonstrates significant architectural skill and social organisation, reflecting the importance of ritual and remembrance in Neolithic society.

Wedge Tombs

Wedge tombs represent the final phase of megalithic tomb construction in Ireland, dating from around 2500 to 2000 BC. Characterised by a wedge-shaped structure that narrows at the rear, these tombs often feature a single gallery and are covered by a cairn. They are predominantly found in the west and southwest of Ireland, with over 500 known examples, making them the most numerous type of megalithic monument in the country.

Notable examples include the Labbacallee Tomb in County Cork, the largest wedge tomb in Ireland, and the Island Wedge Tomb in County Cork, which is accessible to visitors. These tombs are often associated with funerary practices, with excavations revealing cremated human remains and various artifacts.

The orientation of wedge tombs, typically facing southwest, suggests a possible alignment with the setting sun, indicating a cosmological significance in their construction. Their widespread distribution and uniform design reflect a shared cultural tradition during the transition from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age.

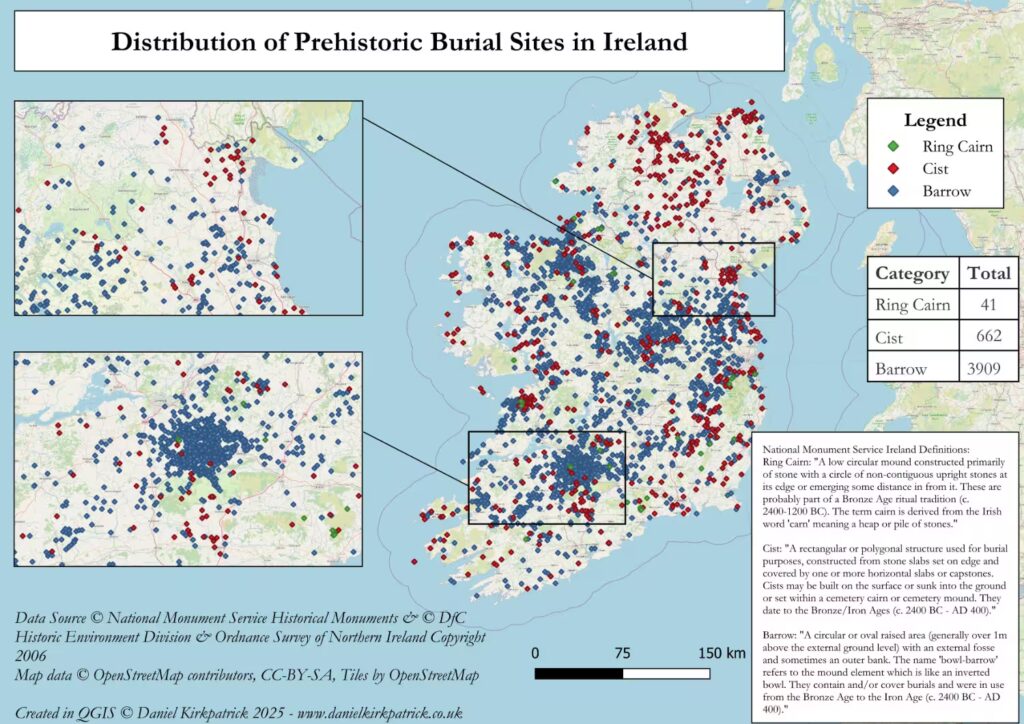

Cists

A cist is much simpler and smaller than the above tombs: essentially a stone coffin built of slabs. Cists date to the later Neolithic and mostly the Bronze (and into Early Iron) Age. They consist of a small rectangular or polygonal box formed by upright stone slabs, with one or more large flat stones laid on top as a capstone. A body (often crouched) was placed inside the box, sometimes on a bed of pebbles or soil, and the grave might be covered by cairn or mound, or simply filled back in. Unlike the grand communal tombs above, cists usually contain a single (or a few) burials. Researchers have found Bronze Age pots, tools or ornaments placed inside cists, indicating they were used by families or small groups. For example, over 30 cist graves are known at the Cairn L cemetery in Co. Galway, some with pottery and metal objects.

In form, a cist is like a stone “box” or chest set in the ground. It might stand alone or lie under a low cairn, but its scale is modest – typically only about a meter long on the interior. Because cists are small, archaeologists often find them by accident (erosion or ploughing unearths a capstone). Their key diagnostic is simply the stone-walled coffin shape.

The National Monuments Service notes that cists “date to the Bronze/Iron Ages (c. 2400 BC – AD 400)” and can be built on or under the surface. In other words, cists mark a shift from the large communal tombs of the Neolithic to individual or family burials of the Bronze Age. We know less of any “ritual” around cists, but their presence – especially with grave goods – speaks to changing funerary customs in later prehistory.

Henges

Henges are a different class of monument: circular earthen enclosures rather than stone chambers. In Ireland (as in Britain) a henge is defined by a roughly circular or oval earthen bank with an internal ditch. Inside this ring is a flat open area more than 50 m across, usually entered by a single gap. The Giant’s Ring near Belfast (Ballynahatty) illustrates the form: it is an oval earthwork about 175 m long with a bank up to 20 m wide, enclosing a level ground. A passage tomb happens to lie at its centre. Henges are ceremonial or ritual enclosures rather than tombs – indeed, while burials occasionally occur inside a henge, it is not primarily a grave site.

Henges in Ireland date to the Late Neolithic or Early Bronze Age (approximately 2800–1700 BC). They often appear in landscapes rich with other monuments: archaeologists note that henges are frequently found near passage tomb cemeteries, as if forming a wider ritual complex. One hypothesis is that henges served as gathering places or ceremonial arenas – imagine an open amphitheater or ritual stadium ringed by earth instead of stone. By contrast, ceremonial enclosures of later date – up to the Iron Age – are much larger circular banks often enclosing entire hilltops, but these are beyond our focus here.

One can picture a henge like a circular “fence” made of earth. The meaning and activities of henges are debated: some may have held timber or stone circles inside, others only open space. But the typical pattern is an intentionally shaped landscape feature used for communal ritual, not a burial chamber. In the Giant’s Ring, for example, the henge bank encloses a flat arena around the central tomb, hinting that the living may have come to the henge for ceremonies, processions or observances.

Souterrains

Souterrains are underground passages or chambers constructed during the Iron Age and Early Medieval periods, primarily between 500 and 1200 AD. Often associated with ringforts, these structures may have served as storage spaces, refuges during times of conflict, or even as places of ritual. Built using dry-stone walling techniques, souterrains are found throughout Ireland, with notable concentrations in counties Louth, Antrim, Galway, and Cork.

Notable examples include the Farrandreg Souterrain in County Louth, which features a complex three-level structure, and the Drumlohan Souterrain in County Waterford, known for its ogham-inscribed stones. These subterranean structures often consist of narrow passages leading to larger chambers, with some displaying evidence of ventilation systems and concealed entrances.

The construction of souterrains reflects the social and political climate of the time, providing secure storage for valuable goods and safe havens during raids. Their enduring presence in the Irish landscape offers valuable insights into the daily lives and survival strategies of early communities.

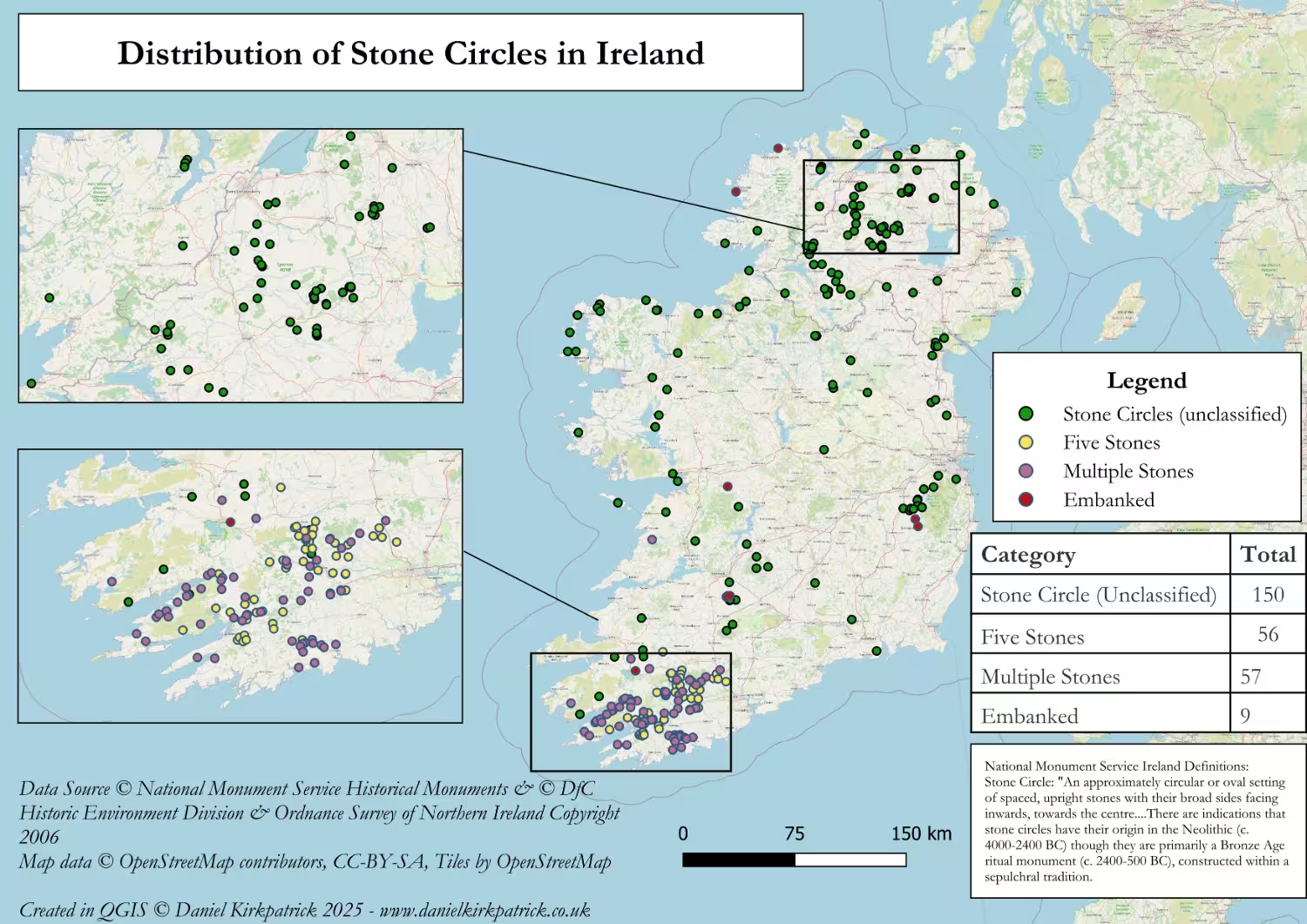

Stone Circles

Stone circles are perhaps the most iconic megalithic monuments outside tomb contexts. As the name implies, they consist of upright standing stones arranged in a ring or oval (sometimes with a central feature like a cist or altar stone). Ireland has roughly 300–350 known stone circles, most erected in the Bronze Age (around 1800–700 BC). Their designs are relatively simple: a ring of 5–20 stones, often with one “axial” stone marking a special point. For example, Drombeg (pictured above) is an “axial stone circle” of 13 slabs in West Cork, famously aligned so that at midwinter the sun sets over its portal stones.

Recent research finds that most Irish stone circles are oriented to the southwest, toward winter sunsets – suggesting they had calendrical or ritual purposes related to the solar year. Importantly, stone circles are not primarily tombs. When human remains are found at circle sites, they tend to be single, perhaps initial deposits made at the time of construction. In general, multiple burials are absent, so archaeologists infer that stone circles were built for ceremonies or as “outdoor temples,” not as cemeteries. By contrast, passage tombs often had many interments. One might imagine standing in a ring of stones marking sacred moments – a kind of prehistoric “clock” or celestial compass.

Many stone circles seem to have developed from earlier practices. In Ireland, some date back into the Late Neolithic, and very large circles sometimes occupy old tomb sites. For instance, the great Newgrange mound is itself surrounded by a 104 m-diameter stone circle, erected after the original tomb was built. Beltany in Donegal (one of Ireland’s largest circles) may likewise incorporate stones from a former passage grave. But most date to the Bronze Age coastal trade era (the Atlantic Bronze Age) when farming communities erected simpler monuments.

Table: Types of Irish Megaliths

| Monument Type | Key Examples | Key Features | Main Time Period |

|---|---|---|---|

| Passage Tombs | Newgrange, Knowth, Dowth (Brú na Bóinne) | Long passage leading to central chamber, often with corbelled roof and carvings | Neolithic (c. 3200–2500 BCE) |

| Court Tombs | Creevykeel (Co. Sligo), Ballymacdermot | Open forecourt leading to segmented burial chambers within long cairn | Early Neolithic (c. 4000–3500 BCE) |

| Portal Tombs | Poulnabrone (Co. Clare), Ballykeel (Co. Armagh) | Upright portal stones supporting a large capstone; originally covered by cairn | Early Neolithic (c. 3800–3200 BCE) |

| Wedge Tombs | Labbacallee (Co. Cork), Carrowmore (Co. Sligo) | Tapered chamber with sloping roof, often aligned with sunset | Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age (c. 2500–2000 BCE) |

| Cists | Rathcroghan (Co. Roscommon), Loughcrew | Small stone-built coffin-like boxes, often for individual burials | Bronze Age (c. 2200–800 BCE) |

| Henges | Giant’s Ring (Belfast), Navan Fort | Circular earthen bank with internal ditch; used for ritual or social purposes | Late Neolithic to Early Bronze Age (c. 3000–2000 BCE) |

| Stone Circles | Drombeg (Co. Cork), Beaghmore (Co. Tyrone) | Circular arrangements of standing stones, sometimes astronomical alignments | Bronze Age (c. 2200–1500 BCE) |

| Souterrains | Knockdrum (Co. Cork), Drumlohan (Co. Waterford) | Underground passages, possibly for refuge or storage | Early Medieval (c. 400–1200 CE) |

Significance Today of Irish Megaliths

With over 7,000 of these ancient monuments documented across Ireland, it’s difficult to overstate their mark on its landscape and history. This post has covered what we know about the original purpose and design of these Megalithic monuments, but many have been used and repurposed throughout the millennia that have followed. They have shaped Irish mythology, Irish history, and continue to shape Irish culture and identity. We see their imagery embedded throughout our contemporary culture, from movies to books, from video games to poetry. So when you see their references today, hopefully now you will have a better understand of what they are and why they matter.

But for those of you who want to explore more, please check out my other posts which cover a wide range of these sites. From Newgrange to the Giant’s Ring, I have written about their specific history and significance. Likewise, you can check out my map of megalithic sites across Ireland which covers these in much more detail.