If I were to list out the Egyptian, Greek, Roman, and Norse cultures, I can almost guarantee that their respective pantheons will come to mind. But if I now add the Irish to this list, I wonder how many would be able to list even one of their gods. Even as someone who grew up in Ireland, I find it incredible how I could have learned about these other religions, but never once touched the Irish gods. And yet, the Irish Tuatha Dé Danann gods are just as impressive, perhaps more so, than these ancient counterparts, and certainly worth our attention.

Unlike these other ancient religions, the Irish gods cannot be reduced to a single family or mythological tradition. With over 400 gods mentioned in historical records, it’s difficult to overstate the complexity of these deities. Local particularities and traditions deeply shaped and dictated what gods were worshipped – or as one scholar puts it: “localized nature deities and shadowy figures of over-arching significance.”1 And while there were certain prominent gods, often there were more than one for each given aspect of worship (such as healing).

Before diving into detailed profiles of each major deity, the following table provides a summary of the prominent Irish gods, highlighting their primary domains, key attributes or symbols, and the main mythic tales or cycles in which they appear. Use it as a quick reference and navigation guide to the gods of Ireland and their roles in the mythos.

Table: 12 Tuatha Dé Danann gods in Irish mythology

| Deity | Domain(s) | Key Attributes & Symbols |

|---|---|---|

| Nuada (Airgetlám) | Kingship, Leadership, the Sun | Silver hand prosthesis; Sword of Nuada (sword of light) |

| Danu (Dana/Ana) | Earth, Fertility, Abundance | Mother of the Tuatha Dé Danann; associated with flowing water and plenty |

| The Morrígan (Morrígu) | War, Fate, Sovereignty | Crow or raven form; shapeshifting hag; trio aspect with Badb and Macha |

| Lugh (Lú/Lámfada) | Crafts, Skills, Kingship | Long spear and sling; many-talented “Samildánach” (master of arts) |

| Manannán mac Lir | Sea, Weather, Otherworld | Mist-covered chariot; magic horse (Enbarr); Sword Fragarach (“Answerer”) |

| Dagda (Eochaid Ollathair) | Fertility, Druidry, Magic | Giant club (kills and revives); Bottomless cauldron; Harp of seasons |

| Brigid (Brigit) | Healing, Poetry, Smithcraft, Spring | Eternal flame; “fiery arrow” inspiration; dual face (beautiful/ugly) |

| Aengus Óg (Macán Óc) | Youth, Love, Beauty, Music | Harp and songs; four bird-symbols of kisses circling his head |

| Ogma (Oghma) | Eloquence, Language, Strength | Ogham script (inventor of writing); champion’s club or bow; “sun-faced” visage |

| Dian Cecht | Healing, Medicine, Magic Wells | Healing slán well; herbs and potions; silver limb craftsmanship |

| Macha | War, Sovereignty, Fertility | Red war-horse imagery; the curse of labour pains; twin sons (in legend) |

| Goibniu | Smithcraft, Hospitality (Ale) | Blacksmith’s hammer and forge; Feast of Goibniu (ale of immortality) |

©Daniel Kirkpatrick

Nuada – The Silver Hand (Sun God of the Tuatha Dé Danann)

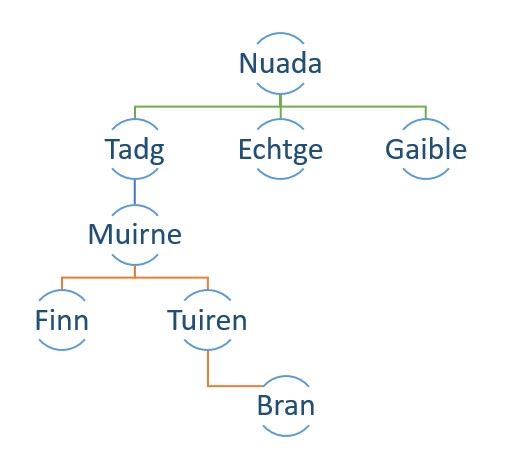

Nuada Airgetlám (“Nuada of the Silver Hand”) is the first great king of the Irish gods. He was worshipped as a sun-deity2 because, as leader of the Tuatha Dé Danann during their arrival in Ireland, Nuada embodies kingship, leadership, and the solar force of the sky.

In the Mythological Cycle, Nuada led the Tuatha in the First Battle of Mag Tuired against the Fir Bolg (the then-inhabitants of Ireland). Though victorious, Nuada lost his right arm in combat. In Irish tradition a king was required to be physically whole, so Nuada’s injury cost him the throne. He was temporarily replaced by Bres – a half-Fomorian prince – but Nuada remained highly respected, often described as a just and shining figure (some later writers even likened him to a sun deity for his radiant leadership).

Nuada of the Silver Hand

Later the healer god, Diancecht, made a new arm of silver resulting in his new name, Nuada the ‘Silver Hand’.3 In the subsequent Second Battle of Mag Tuired, Nuada fought alongside his people against the demonic Fomorians. Although he was slain in that war by the Fomorian giant Balor, the Tuatha ultimately triumphed – thanks to the heroism of Lugh, who avenged Nuada. Nuada’s sacrifice and leadership left a lasting mark: many later Irish heroes and kings traced their lineage back to Nuada, reinforcing his image as a patriarch of the Irish divine bloodline.

In terms of attributes, Nuada possessed one of the Four Treasures of the Tuatha Dé Danann: the Sword of Nuada, also called the Sword of Light. This fabled weapon was said to never fail in battle. Nuada himself is portrayed as a noble warrior-king, often armed and sometimes associated with brilliant light or the sun’s energy. In comparison to other pantheons, Nuada parallels the archetype of the dismembered king – a leader who is wounded but remains spiritually potent (similar to legends of the Fisher King). His leadership role and sky associations also draw loose parallels to sky-father gods like Zeus or Odin, though Nuada’s story is uniquely his own.

Dana the Great Mother Goddess

Danu (also called Dana or Anu) is revered as the great Mother Goddess of Ireland. The very name Tuatha Dé Danann means “the Tribes of the Goddess Danu,” highlighting her status as the divine matriarch of the Irish pantheon. Although Danu’s appearances in narrative myths are scarce, her influence permeates the mythological landscape as a personification of the land’s fertility, abundance, and prosperity. She is the earth-mother who nurtures both gods and the earth itself.

Irish goddess of Fertility

Often associated with the nourishing aspects of nature, Danu is linked to plenty and fertility. Two mountains near Killarney are still known as ‘the Paps’ as if they were the breasts of the land giving life – a lasting tribute to the goddess’s nurturing power. Some scholars also connect Danu to water, noting that the name Danu appears in the names of major rivers like the Danube (hinting at a pan-Celtic river goddess), though such connections are theoretical. In any case, water and earth – sources of life – are fitting elements for Danu’s domain.

In Irish myth, Danu’s children (the Tuatha Dé Danann) came to Ireland with her blessing. When they settled, it was effectively Danu’s people who had arrived. We don’t have detailed stories of Danu’s deeds, but her legacy is the identity of the Irish gods themselves – they carry her name as a badge of honour.

Some believe Dana was later worshipped as Brigit rather than her being a separate god.4 Though I personally find this unconvincing given the various differences between them. Though there were likely elements borrowed or later coopted into religious traditions which followed.

Morrigan (or Morrigu) the Phantom Queen

Mysterious and fearsome, The Morrígan is one of Ireland’s most famous goddesses. Her very name means “Great Queen” or perhaps “Phantom Queen” (from Mór-Ríoghain in Irish), and she lives up to that title on the battlefield. The Morrígan is the goddess of war, fate, and death – a shape-shifting female deity who presides over the frenzied chaos of combat. In myths, she often appears as a hooded crow or raven, or as “a loathsome-looking hag,”5 flying above warriors and shrieking to instil terror or to herald doom. Many a Celtic warrior heading into battle would have dreaded seeing a raven on the left, interpreting it as the Morrígan’s presence and an omen of slaughter.

Triumvirate of goddesses

In the Mythological Cycle, the Morrígan features prominently during conflicts. Along with two other war goddesses (her sisters Badb6 and Macha), she unleashes clouds of mist, magical darkness, and confusion upon enemy armies. For example, in the first battle against the Fir Bolg, the trio conjured fog and a rain of blood to terrorise their foes.7 The Morrígan delights in the carnage, “washing” the blood of warriors in battle — a motif that later blends into the folkloric image of the banshee (bean sídhe), a female spirit who washes the clothes of those about to die.

The Morrígan is essentially the chooser of the slain and the weaver of destiny in battle, not unlike the Valkyries of Norse myth who decide who lives or dies. Her presence can turn the tide: in the Second Battle of Mag Tuired, she aids the Tuatha Dé Danann by attacking and distracting the Fomorian king, and after victory she chants a prophecy of Ireland’s future glory and eventual doom.

Morrigan and Cú Chulainn

The Morrígan’s ability to shape-shift sets her apart. She can appear as a withered old hag, a beautiful young woman, a crow, a wolf, or even a heifer, depending on the tale. One famous story in the Ulster Cycle describes her multiple encounters with the hero Cú Chulainn. Initially, she offers him love and aid as a maiden; when he rebuffs her, she plagues him in battle by taking the forms of an eel (tripping him), a wolf, and a red cow, causing him injuries. Despite her mischief, Cú Chulainn wounds her each time.

Later, the Morrígan meets him again as an old woman milking a cow; she tricks him into blessing her, thus healing the injuries he himself gave her. In the end, she ominously foretells the hero’s own death. This illustrates her role as a fate-spinner – those who reject the Morrígan may suffer, for she holds power over their destiny.

Lugh of the Long Arm

Lugh (pronounced “Loo”) is the bright young hero of the Irish pantheon, often called Lugh Lámfada (“Lugh of the Long Arm”) for his deadly long spear arm or skill with a sling. He is a god of many talents – so many that one of his epithets is Samildánach, meaning “equally skilled in all arts.” Lugh’s domain encompasses crafts, warfare, music, poetry, and leadership; in short, he’s the polymath of the gods. Where most deities have a single specialty, Lugh excels at everything he tries.

Lugh succeeded Nuada as King of the Men of Dea. During the decisive Second Battle of Mag Tuired, it is Lugh who slays the Fomorian giant-king Balor. In a dramatic twist, Balor was Lugh’s own grandfather in some accounts – a prophecy said Balor would be killed by his grandson, which Lugh fulfills by using his sling or spear to destroy Balor’s evil eye. With Balor defeated, the Fomorian threat collapses, and Lugh secures freedom for the Tuatha Dé Danann. After the battle, Lugh becomes the High King of the Irish gods for many prosperous years.

Lugh’s Many Talents

Lugh’s attributes include several legendary weapons. Chief among them is the Spear of Lugh, one of the four sacred treasures of the Tuatha. This spear was unbeatable in battle, reputed never to miss its mark and sometimes said to be so bloodthirsty it had to be kept in a pot of water to prevent it igniting into flames. Lugh is also associated with the sling – it’s with a sling-stone that he strikes down Balor’s poisonous eye.

In addition to martial prowess, Lugh is depicted as a patron of the arts. He’s a harper and poet, credited with bringing games and festivities to Ireland. In fact, the annual harvest festival Lughnasadh (held around 1st August) is named after him. Lugh established this festival in honour of his foster-mother Tailtiu, and it became one of the great seasonal celebrations in Gaelic culture, marking the beginning of the harvest and featuring fairs, athletic contests, and feasting. Through Lughnasadh, Lugh’s memory lived on at folk level, as people celebrated the bounty of the land under the auspices of this versatile god.

Lugh is said to be the father of Cú Chulainn, the greatest hero of the Ulster Cycle. Some legends also make Lugh a distant ancestor or even foster-brother of Fionn mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool) of the later Fianna cycle, thus threading Lugh through all eras of Irish myth.

© Conall

Manannan mac Lir, Son of the Sea

Manannán mac Lir is the god of the sea in Irish mythology, a figure wrapped in mist and magic. As the son of Lir (whose name simply means “Sea”), Manannán’s realm is the ocean that surrounds Ireland, and by extension the mysterious lands beyond the mortal world’s horizon. Sailors, navigators, and anyone traveling to the mystical “west” would invoke Manannán mac Lir. He is portrayed as a wise and powerful guardian of the Otherworld, often aiding or testing heroes who wander into his domain. Many of Ireland’s otherworldly isles and enchanted fog-banks are part of “Manannán’s country.” Fittingly, the Isle of Man (located in the Irish Sea) is named after him – according to legend, Manannán protected the Isle of Man by shrouding it in eternal mist so it would remain hidden from invaders.

In appearance, Manannán is sometimes depicted as a mighty warrior in gleaming armour, driving a chariot across the sea’s waves as if they were solid ground. On land, he had three-legs on which he rolled along, wheel-like. The waves obey him, and the veil between worlds is at his command – he can stir up uncanny fogs or clear them just as easily.

Mannan’s Magical Possessions

A section of folklore surrounds his magical possessions. For instance, he owns the horse called Enbarr (Aonbharr) which can gallop over water as swiftly as over land, never allowing a rider to drown. He carries a sword named Fragarach, “The Answerer,” which can slice through any armour and forces truth from those beneath its blade. In ancient myths he is usually depicted riding on his sea-chariot and surrounded by mist. .

His horse, the Aonbharr, was “as swift as the naked cold wind of spring, and the sea was the same as dry land to her, and the rider was never killed off her back”. Manannan’s breastplate would protect whoever wore it from wounds, and his helmet was set with precious stones. His sword, the Freagarthach, the Answerer, would be fatal to anyone wounded by it.8 Manannán also had a crane-skin bag full of treasures and tricks, and a cloak of invisibility that could change colours like the sea’s shifting hues. In some tales, he even has a boat that sails itself without oar or sail, obeying his thoughts – a predecessor to self-navigating ships of fantasy.

© Daniel Kirkpatrick

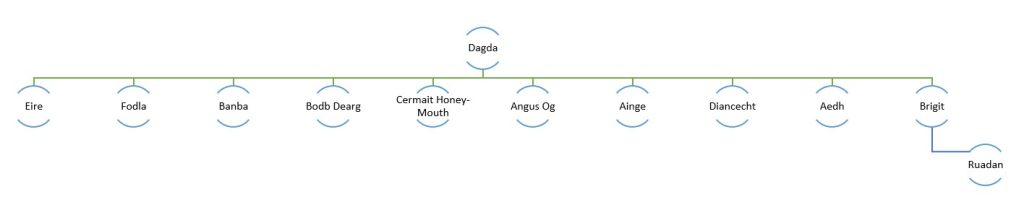

Dagda – The Good God

The Dagda (pronounced “DAHG-duh”), whose name means “the Good God” or “Goodly Druid,” is a central figure in Irish mythology – a chieftain of the Tuatha Dé Danann and a god of strength, abundance, and magic. Far from “good” in a moral sense alone, “good” here means good at everything: the Dagda is masterful in many roles. He’s a warrior, a druid, a harper, a builder, and a ruler. Often depicted as a large, earthy man with a hearty appetite and a sense of humour, the Dagda is sometimes called Eochaid Ollathair (“All-Father”), reflecting his role as a patriarch among the gods. He indeed fathers many other deities, including Brigid, Aengus Óg, Midir, Bodb Derg and others, making him a progenitor of divine bloodlines.

He fathered many of the other gods listed here. Along with Nuada, he is considered a sun-god and one of the most powerful of the deities. His wife was the river goddess Boann (which the river Boyne takes it name from) and he is believed to have resided in the ancient tomb Brug na Bóinne (Newgrange).9

Dagda succeeded Lugh as the King of the Tuatha de Danann. Later Dagda was thought to have become ‘King of the Fairies’, retreating into the hills and mounds after his defeat by the Milesians, forming an invisible world of their own.10 For centuries after, these fairy-hills were widely feared and held with great superstition throughout Ireland as the homes of fairy-folk.

Dagda’s Gifts

He carries a massive club or mace called Lorg Mór. This weapon is so powerful that one end can slay nine men in a single swing, while the other end can resurrect the dead – showing his control over life and death. The Dagda also possesses the Coire Ansic (the “Undry Cauldron”), a great cauldron that never runs empty and can feed all who come to it. This magic cauldron ensured none of his people would go hungry – symbolising abundance and generosity.

Furthermore, the Dagda is a musician: he owns the Uaithne, a magic harp that can command the seasons or control men’s emotions. In one tale, when the harp is stolen by adversaries, the Dagda summons it and plays three magics on it – the music of sorrow, of joy, and of sleep – to overcome his foes. These treasures mark the Dagda as a culture-bringer and sustainer of his tribe. He is also said “to have been master of druidery and a warrior leader, as well as a man capable of building some of the major fortresses in Ireland”.11

Brigid the Fiery Arrow

Brigid (pronounced “Brih-jid” or “Bree-id”), also spelled Brigit or Brighid, shines in Irish lore as a goddess of inspiration and renewal. She is a daughter of the Dagda and one of the most widely beloved deities, so much so that her memory persisted into Christian times as Saint Brigid.

She was worshipped by poets and as a woman of healing and smithing: “it was she [who] first made the whistle for calling one to another through the night”. This makes her a patron of creative and skilled endeavours as well as the new life that comes with the spring. In many ways, Brigid is the personification of the fire of inspiration and the hearth – the life-giving flame that warms, heals, and provokes creativity.

Goddess of Spring

One aspect of Brigid’s legend hints at a dual nature: “one side of her face was ugly, the other side beautiful,” implying she could appear as both a fearsome older woman and a youthful lady. This dual visage may symbolise her command over both life and death, or the contrasting realities of the creative process (pain and beauty). It also resonates with the changing seasons: winter’s harshness versus spring’s beauty, and Brigid stands at that threshold as the spring goddess.

In Irish tradition, the festival of Imbolc (around 1st February) is Brigid’s holy day, marking the stirring of life in the earth as lambs are born and the first buds appear. People lit bonfires and hearth fires for Brigid, and to this day St. Brigid’s Day and Candlemas carry echoes of that celebration of returning light.

© Pam Corey

Ogma (or Ogmé) the Sun-Faced

Brother of king Nuada, and son of Elada, Ogma (also spelled Oghma) is the strongman and sage of eloquence among the Irish gods – the ‘sun-faced’.12 As a high-ranking member of the Tuatha Dé Danann, Ogma is credited with one of the greatest gifts to Irish culture: the invention of Ogham writing, the first written alphabet used for the Gaelic language.13 Because of this, he’s honoured as a deity of language, speech, and learning.

Yet, Ogma is no cloistered scribe – he’s equally celebrated as a warrior champion, renowned for his physical might. This dual identity as a man of words and a man of action makes Ogma a fascinating figure embodying the Celtic ideal of the warrior-poet.

God of the Bards

In mythological genealogies (which vary), Ogma is sometimes described as a son of Elatha (a Fomorian prince) and thus related to Bres. This parentage hints at a link between the Tuatha and their rivals, perhaps symbolising that wisdom can come from balancing opposing backgrounds. Ogma fought alongside his brethren in the battles for Ireland. During the Second Battle of Mag Tuired, he proved his valour by wielding a sword and hefting massive loads of weapons. One tale recounts Ogma’s feat of arms: spurred by battle-fury, he seized a chain of the defeated enemy and dragged thirty Fomorian captives singlehandedly back to the Tuatha camp – a testament to his sheer strength.

Ogma’s skill with words was not just literal but also magical. In some stories, he could enchant people with his speech, binding them to his will. This concept is vividly illustrated by a later parallel from Gaulish lore: the Romans recorded that the Gauls worshipped a deity they identified with Hercules, but unlike the Greek Heracles, this god (called Ogmios by Lucian of Samosata) was portrayed as an old man with a bow and club, who had chains running from his tongue to the ears of his followers. This is almost certainly the continental Celtic version of Ogma.

Dian Cecht the Healer

Another of Dagda’s many children, Dian Cecht (pronounced roughly “DEE-an KEKHT”) was the healer or physician of the Tuatha de Danann. He made Nuada a replacement silver arm after he’d had the limb severed in the battle against the Firbolg. His very name may derive from old Irish elements meaning “swift power,” which suits a doctor who must act quickly to save lives. In an age of constant conflict, Dian Cecht’s skills were absolutely vital, making him an unsung hero in the background of the war stories.

The Jealous God

His son, Miach, was a better healer than he. But Dian Cecht – filled with jealousy – struck him in the head three times, each time Miach healed the wound, until the fourth blow finally killed the young healer. From Miach’s grave, however, sprang 365 herbs – all the healing plants of the world – which Airmed, Miach’s sister, arranged and catalogued on her cloak. Heartbreakingly, Dian Cecht scattered the herbs, muddling them up, so that humanity would not so easily have the full knowledge of healing (only Dian Cecht and Airmed would retain some knowledge). This myth may symbolise the idea that the secrets of medicine are hard-won and easily lost – and possibly a caution against jealousy stifling progress.

He used herbs and spells to turn a well into a healing well, healing all the warriors who bathed in its waters during the Battle of Magh Tuireadh. In later Irish folklore, Dian Cecht’s direct presence fades, but folk healers and practitioners of herbal medicine could be seen as carrying a spark of his power. The idea of a holy well with curative properties, common throughout Ireland, is a gentle echo of that grand Well of Slaíne he created.

Macha the Vengeful

Macha is a name that appears several times in Irish legend, hinting that Macha is less a single personage and more a title or incarnation of a goddess power. All the Machas, however, share common themes: warfare, horses, and sovereignty. In essence, Macha straddles the roles of a war goddess and a fertility goddess. This might seem contradictory, but in Celtic belief, the cycle of life and death are intertwined. War brings death (and possibly new beginnings), fertility brings life (but life that will eventually die). Macha embodies that cycle. Her use of childbirth as a weapon is a striking inversion – making warriors feel the vulnerabilities of creation rather than destruction.

As goddess of fertility, she is the namesake of Emain Macha. As the myth goes, she became the wife of Cruinniuc and became pregnant. But was forced by the men of Ulster to race against the king’s horses, to entertain the court, because her foolish husband boasted she was faster. Macha begged for a reprieve until after she gave birth, but the men refused. This pregnant Macha died after laying a curse, and giving her name to Emain Macha (Navan Fort in Armagh), which was the seat of the Ulster kings. Emain Macha literally means “the twins of Macha” or “Macha’s brooch” (depending on translation), supposedly named because Macha marked the site with her twin babies or perhaps a brooch she cast.

Goibniu the Smith

Goibniu (pronounced “Gov-nyoo”) is the smith of the Tuatha Dé Danann, a god of blacksmiths, metallurgy, and also hospitality. In Irish myth, craftsmanship – especially the crafting of weapons – is a sacred art, and Goibniu is the master of it. His forge equipped the gods with their superior arms, and his skill in metalworking made him indispensable in war and peace alike.

The name Goibniu is related to the word for smith (Old Irish gobha). He is one of a trio of craftsman brothers, along with Credne (a brazier worker in bronze) and Luchta (a wright or carpenter). Together they were known as the Trí Dé Dána, the “three gods of craft,” who manufactured the magical weapons that the Tuatha Dé Danann used. During the battles with the Fomorians, Goibniu would forge spears and swords that never missed and never dulled, while Credne made the rivets and hilts, and Luchta made the shafts – a perfect assembly line of divine artisans. Thanks to Goibniu’s unbeatable blades and tips, the Tuatha’s warriors always had an edge (literally!) over their foes.

Goibniu’s Feast

Goibniu also had a special feast which conferred immortality to the gods and “consisted principally of beer” of which Goibniu was the brewer.14 In mythic references, Goibniu’s Feast (Fled Goibnenn) was a otherworldly banquet where the gods dined to replenish their vitality. At this feast, Goibniu served a special ale or beer that granted immortality (or at least eternal youth) to those who drank it.

This concept mirrors the nectar and ambrosia of the Greek gods or the Norse gods’ apples of Idun – but in Irish style, it’s a hearty brew that does the trick, reflecting the importance of ale in ancient Celtic culture. The ale of Goibniu was so renowned that even in later Christian texts, “the Feast of Goibniu” became a metaphor for heavenly feasting.

Aengus Óg the Young

Aengus Óg (pronounced “ANG-guss Ogue”), also known simply as Aengus or Angus, is the Irish god of love, youth, and poetic inspiration. His epithet “Óg” means “young,” reflecting that he is eternally youthful. Aengus is the son of two powerful deities – the Dagda and Boann (the river goddess of the Boyne) – and his birth is laden with magic and intrigue.

According to myth, the Dagda, made the sun stand still in the sky for nine months so that Boann could bear Aengus in one day, hiding the affair from her husband. Thus Aengus was miraculously conceived and born within a single day. Growing up, he resided at his father’s house, the Brú na Bóinne (Newgrange), and eventually tricked the Dagda into giving him that grand dwelling permanently.

Irish God of Love

Aengus Óg is most renowned for his romantic adventures, the most famous being the tale of Aengus’s dream. One night he dreams of a beautiful maiden and becomes utterly lovesick for her, refusing to eat or sleep until he finds her. With the help of his mother Boann and others, Aengus searches all over Ireland for this dream-girl. After a year, they locate her: she is Caer Ibormeith, a maiden who lives by a lake and transforms into a swan every other year.

When Aengus arrives, he sees many swan-maidens on the lake. To win Caer, he must identify her among the flock. Aengus, turning himself into a swan as well (shape-shifting being in a Tuatha Dé Danann’s repertoire), calls out to Caer. They find each other, and together they fly off as swans, singing such a beautiful song that all who hear fall asleep for three days. Aengus and Caer thus become united, and he brings her home to Brú na Bóinne as his love. This dreamy, lyrical story cements Aengus’s reputation as a god of love and poetic dream, often earning him the nickname “the Celtic Cupid.”

In iconography, Aengus is associated with birds – it’s said that four small birds always flutter about his head. These birds are described as the physical manifestations of his kisses, spreading love wherever they go.

Legacy of Irish Mythology

Understanding the gods of Ireland gives us a window into the values and fears of ancient Irish society. In many ways, these 12 were not gods like the Greek or Roman pantheons. The quasi-historical narrative has led some to describe their veneration as ancestor worship rather than a religion per se. The truth is likely somewhere in between. Local communities would have prayed and worshipped the things beyond their control, whether that be the sea, rain, sun or many health. In this way, the gods are symbolic of the societies that worshipped them. They represent the struggle and joys of the ancient Irish.

I will conclude with one final reflection. For I wonder what someone 2,000 years from now would say our gods are today. We may not have Nuada or Morrigan, but I suspect they could see worship of our modern day gods as readily as we do with the ancient Irish.

Frequently Asked Questions: The Gods of Ireland

The Tuatha Dé Danann (meaning “Tribe of the Goddess Danu”) are the legendary gods of Ireland who arrived in a mystical cloud and brought magic, wisdom, and divine order. After their defeat by the Milesians, they were said to have retreated into the sídhe, becoming the ancestors of the fairy folk.

While not worshipped in a traditional religious sense, many Irish gods are honoured in modern Pagan and Celtic reconstructionist practices. Figures like Brigid remain influential in both pagan spirituality and Irish Christian folklore through Saint Brigid.

The Aos Sí are the supernatural beings of Irish folklore, often described as fairies or spirits. In mythology, they are believed to be the descendants or transformed forms of the Tuatha Dé Danann, living in hidden hills and mounds (sídhe) after their mythical defeat.

The main sources include:

Lebor Gabála Érenn (Book of Invasions)

Cath Maige Tuired (Battles of Mag Tuired)

The Metrical Dindshenchas (lore of Irish place-names)

These texts were written by medieval Irish monks who recorded pre-Christian mythology alongside Christian history.

- Downham, Clare. “A Review of Ireland’s Immortals: A History of the Gods of Irish Myth.” International Yeats Studies 2, no. 1 (2017): 76. ↩︎

- Bonwick, J., 1894. Irish Druids and old Irish religions. S. Low, Marston., p134. ↩︎

- Gregory, Lady. Gods And Fighting Men The Story Of The Tuatha De Danaan And Of The Fianna Of Ireland Arranged And Put Into English. BoD–Books on Demand, 2024., p37. ↩︎

- Bonwick, p141. ↩︎

- P.W. Joyce, A Smaller Social History of Ancient Ireland, Dodo Press, p81. ↩︎

- She is sometimes called Badb, the warrior goddess, though the two names typically refer to different gods depending on the source. ↩︎

- Gregory, p30. ↩︎

- Gregory, p44. ↩︎

- Though Newgrange’s mythological traditions are by no means restricted to Dagda as noted by Swift, 2003. ↩︎

- Bonwick, p104. ↩︎

- Swift, C., 2003. The gods of Newgrange in Irish literature & Romano-Celtic tradition., p56. ↩︎

- Bonwick, p145. ↩︎

- For more on its history see: https://www.historytoday.com/story-ogham ↩︎

- Bonwick, p144-45. ↩︎